Finding faith

Religious groups spark global citizenship

A. Sue Weisler

From left, Hillel members Bryan Goldstein, Jared Krichevsky and Samantha Geffen participate in a service.

After the Muslim students finish rolling up their prayer rugs, Jewish students begin setting up for Shabbat dinner.

Later, Campus Crusade for Christ will play games and worship and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship will host its large group meeting on topics varying from building community to “Why are we here?”

By the end of the weekend, about 1,000 RIT students will have taken advantage of programs or services offered by the Center for Religious Life, up from half that number a decade ago, says Jeff Hering, director of the center.

“Students, in my opinion, will not simply believe because the tradition says it is true,” Hering says. “They want the experience and exploration for themselves of what this means, to be in this community, to be in this discipline. They want to ask why.”

There are nine formal religious communities at RIT—Gospel, Jewish, Lutheran, Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Muslim, Zen Buddhism, Campus Crusade for Christ and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship—as well as a handful of smaller student clubs. The Muslim Student Association, because of exchange programs with RIT Dubai, has seen significant growth.

Chaplains and program directors, who hold part-time appointments and sometimes work with students at more than one university, lead the groups. Their salaries are paid by the religious organizations.

Although they represent different religions, the chaplains work side-by-side on interfaith initiatives and organize their own group projects, community service and religious programs. Those projects range from the Jewish group Hillel’s discussion on Israel 101 to the Catholic Newman Community participating in the Polar Plunge in Lake Ontario to raise money for the Special Olympics.

All the groups share the same goal of being there for the students and making programs relevant to their lives.

Religion at college is a topic that is often considered taboo, says Alexander Austin, an author of Cultivating the Spirit, How College Can Enhance Students’ Inner Lives. And spirituality and religious development at college haven’t been studied much until now.

His seven-year research study showed that although students’ religious involvement declines during college, their spirituality grows. Students become more caring, more tolerant and more connected with others.

“The main thing about a college experience is that students are exposed to new people, races, cultures and geographic regions,” Austin says.

“This begins to broaden their perspective and raise questions about what life is all about and why I am here.”

Growing communities

One by one the young men walk down the stairs of the Kilian J. and Caroline F. Schmitt Interfaith Center. They set down their backpacks, pull off their sneakers or boots and carefully place them along the wall.

Some wait for their turn at the ablution station, where they can wash before the Friday afternoon Jumu’ah Prayer.

Colorful rugs have been set out for the men to kneel on while praying in the Skalny room in the basement of the Interfaith Center.

Rauf Bawany, the Muslim chaplain, starts the service with a call for prayer and then begins his sermon. As Bawany talks, students quietly file into the room and search for an empty spot on the floor. In a small room next door, three women pray together and listen to Bawany on an intercom. The Friday prayer is an obligation for men only and the women participate in a different room following the religion’s traditions.

After the sermon, the men, who now number more than 60, stand together shoulder to shoulder in neat rows. They pray together before returning to their college routine of class, lab work or homework.

Bawany says more than 300 students coming from more than 33 countries participate in the Muslim Student Association.

Sheraz Rashid, president of the Muslim Student Association, says half of the participants are international students creating a group with different cultural backgrounds.

“This group is extremely important when people come on campus and they come from a Muslim country, they are trying to find ways to assimilate,” he says.

But there are other factors attracting Muslim students, Bawany says. The ablution station was dedicated in 1999 and, Hering says, at that time RIT was one of only three universities in New York with such a station.

RIT also sells Halal food—food permitted under Islamic dietary laws—in campus cafeterias and in campus stores. Bawany says it is unusual for a university to pay attention to such concerns and shows that building an inclusive campus environment is a priority for RIT. The food became available last year.

Other communities are also growing.

Hillel sees about 100 students during the course of a year. Nearly 40 of those participate in two free Friday night Shabbat dinners a month, double the number from last year.

Kourtney Spaulding, Hillel program director, says many of the students are looking for a cultural experience more than a religious experience.

First-year interpreting student Beth Minowitz wanted a place where she would fit in. Her brother was active with Hillel at the University of Minnesota and she thought she could find the same comfort at RIT. She met Spaulding last fall at freshman orientation.

“I was welcomed with open arms,” she says.

Jared Krichevsky, a fifth-year mechanical engineering student, says his involvement with Hillel has given him a better sense of the diversity of Judaism.

He has met Jews from Israel, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, big cities and small rural areas with tiny Jewish populations. Krichevsky, who is from a suburb of Washington, D.C., says he likes learning different perspectives on the same religion.

John Iamaio, leader of Campus Crusade for Christ, says his group has about 70 participants, up from about 30 when he started four years ago. His interdenominational Christian group hosts social events, does community service projects and has small group meetings called life groups during the week.

“I think college is meant to be this experience where people can interact,” Iamaio says. “They are at a point in their life where they are naturally questioning things.”

Personal development

Curtis Columbare was involved with his Christian church when he was growing up in Jamestown, N.Y., but that involvement meant just attending Sunday services.

His first week on campus, Columbare attended an InterVarsity Christian Fellowship event.

In Columbare’s second year, he participated in small-group Bible discussions and became a small group leader. His third year, he was a coordinator of small groups, which are made up of six to 15 people with similar interests who study the Bible.

And this school year, the environmental sustainability, health and safety major became president of InterVarsity until January, when he moved to Ohio to accept a co-op with Honda.

“I went from being a small-group attendee to serving on the leadership board,” he says. “I learned so much from being a leader that will carry into my career. I have grown so much these four years.”

Columbare says his spiritual growth from InterVarsity helps him live a balanced life centered on God.

Nathan Krause understands the impact a religious group can have on a college student. He wasn’t involved in religious activities when he was in college at the University of Arizona and knows what it is like to not have a support system.

As the new chaplain of the Lutheran Campus Ministry, he is excited about working with students and getting more participants. The group has about 10 active members who participate in a weekly Sunday worship as well as a free dinner following the service.

“I would like to see it as a community that can be open in dialogue about their faiths and doubts and accepting of many different people,” Krause says.

Hering says what pleases him as director is the acceptance of different religions and the way students break down stereotypes.

“You can come in as a Jew and talk to a Muslim student and realize, though you may have profound disagreements, including politically, there can be mutual respect,” Hering says. “There is a message of global citizenship.”

That message is being noticed. Spaulding, who started working with Hillel in August, says her grandfather was visiting RIT and commented on the cooperation of the different communities.

“He said, ‘If only the rest of the world could work together like you all do here.’”

The Jewish student group Hillel has regular Friday night services and Shabbat dinners twice a month. A. Sue Weisler

The Jewish student group Hillel has regular Friday night services and Shabbat dinners twice a month. A. Sue Weisler InterVarsity member Audra Rehbaum, right, talks to students during a social justice fair hosted by InterVarsity that connected students to community groups and volunteering opportunities. A. Sue Weisler

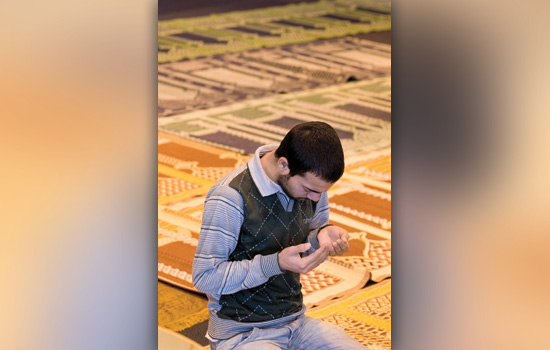

InterVarsity member Audra Rehbaum, right, talks to students during a social justice fair hosted by InterVarsity that connected students to community groups and volunteering opportunities. A. Sue Weisler Muslim students prostrate toward the Ka’ba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during the Jumu’ah Prayer. The service is an obligation for Muslim men. A. Sue Weisler

Muslim students prostrate toward the Ka’ba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during the Jumu’ah Prayer. The service is an obligation for Muslim men. A. Sue Weisler The Gospel Ensemble performs during Big House, an event held Jan. 28 for Christian clubs on campus. A. Sue Weisler

The Gospel Ensemble performs during Big House, an event held Jan. 28 for Christian clubs on campus. A. Sue Weisler Buddhist Chaplain Shudo Brian Schroeder leads meditation sessions on Wednesdays and Saturdays in the Center for Religious Life. He has been involved with Zen Buddhism for 35 years. Here participants follow his lead in the Allen Chapel. A. Sue Weisler

Buddhist Chaplain Shudo Brian Schroeder leads meditation sessions on Wednesdays and Saturdays in the Center for Religious Life. He has been involved with Zen Buddhism for 35 years. Here participants follow his lead in the Allen Chapel. A. Sue Weisler Muslim students wait in line to use the ablution station before the Friday afternoon Jumu’ah Prayer. RIT is one of few universities in New York with such a station. A. Sue Weisler

Muslim students wait in line to use the ablution station before the Friday afternoon Jumu’ah Prayer. RIT is one of few universities in New York with such a station. A. Sue Weisler Khalid Amiri, a Fulbright Scholar from Afghanistan, prays following the Friday Jumu’ah Prayer in the Kilian J. and Caroline F. Schmitt Interfaith Center. A. Sue Weisler

Khalid Amiri, a Fulbright Scholar from Afghanistan, prays following the Friday Jumu’ah Prayer in the Kilian J. and Caroline F. Schmitt Interfaith Center. A. Sue Weisler