Books

Let Us Not Forget

by Irene Teger

“My Dear Son…..”

“She didn’t look at me with sympathy any more. She began to scream: “Do you want to bring death to the whole nursery? If the Nazis find you here, they will kill all of us….Please go away.”

“I went to a Gentile nursery. The leading sister told me that she would keep you from nine till five. She told me to give her your birth certificate….I began to cry. When she saw that I couldn’t stop crying, she put her arms around me with sympathy. “Sister,” I said, “I can’t give you my child’s birth certificate….We are Jewish.”

“Slowly I went to the door, but she called me back. She told me to sit down and began to speak slowly and quietly: “My poor, poor woman. I am over seventy. I hope they won’t touch the innocent children, and if they kill me, I will sooner see Our Father in Heaven….Leave your baby here.”

“It wasn’t possible for me to thank her. In a dream I turned to the door and walked out……”

Teger, Irene. Let us not Forget: A Mother’s Letter to a Son. New York: Pyramid Books, 1974. RES, 1st floor Durr Book #1. Available online courtesy of the Teger family.

Deaf Victims of the Atomic Bomb

Takeshi, Mamezuka. Don ga Kikoenakatta Hitobito: The Deaf and the Atomic Bomb. Kyoto, Japan: Bunrikaku, 1991. In Japanese. 4th floor D767.25.N3 M36 1991.

Introduction

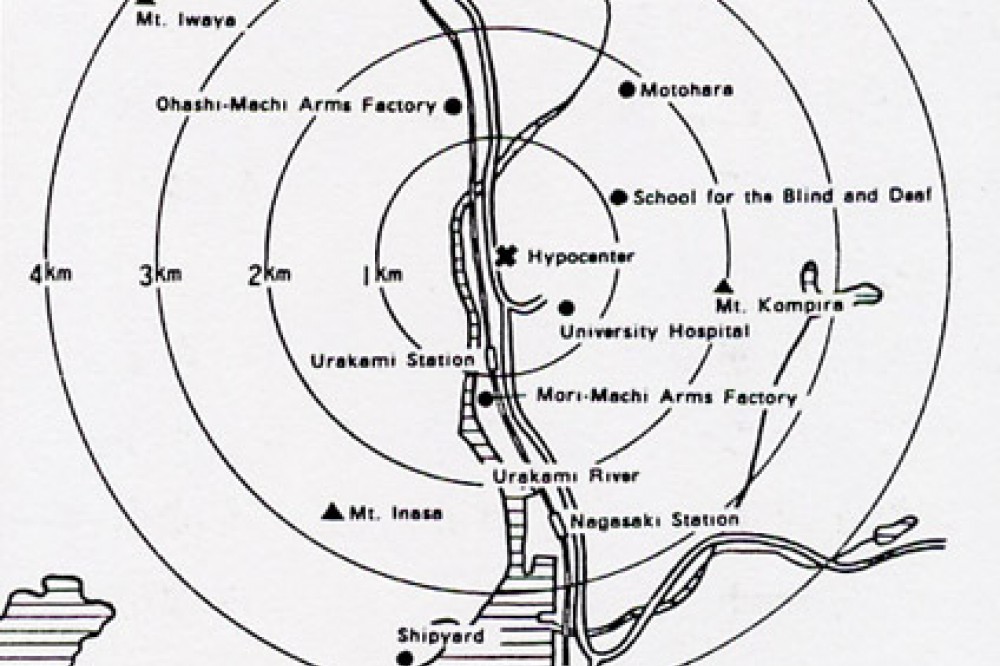

It has been 45 long years since an atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and the scars it left have been sealed deep inside the beautiful city once called the Naples of the Orient.

Even now, though, there are still people suffering from the effects of radiation sickness and struggling with the fear of death, as they continue on with their lives and with relating their story to others.

In Nagasaki, there is one time period that ended at two minutes past eleven, and another moving ahead in a present progressive tense that began at two minutes past eleven, August 9, 1945. Forty some years after the shift, people were made aware that part of the present progressive tense is the Nagasaki of people who were unable to hear the bomb’s bang. Much has been told and written of the experiences of the bombing victims with normal hearing. They have come to be well known. Deaf and dumb victims, though, were passed by, a forgotten existence sunk in an abyss of silence.

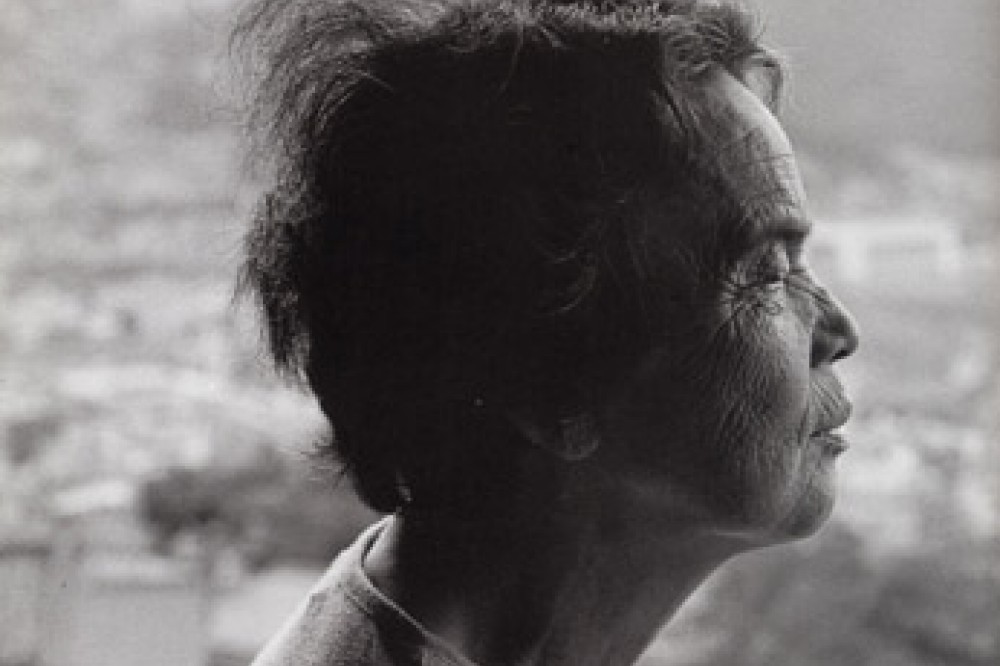

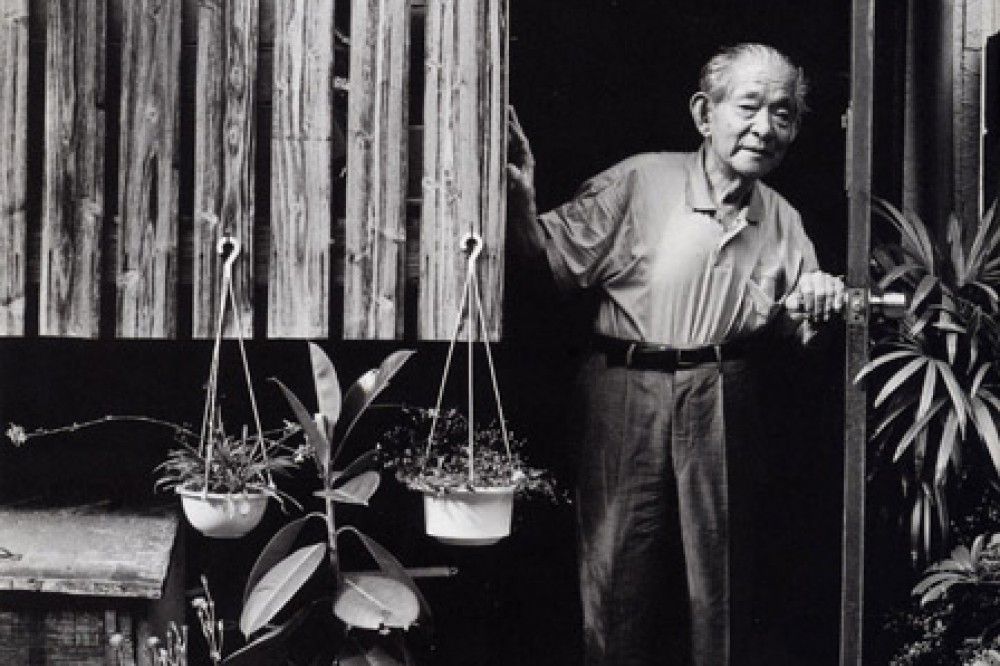

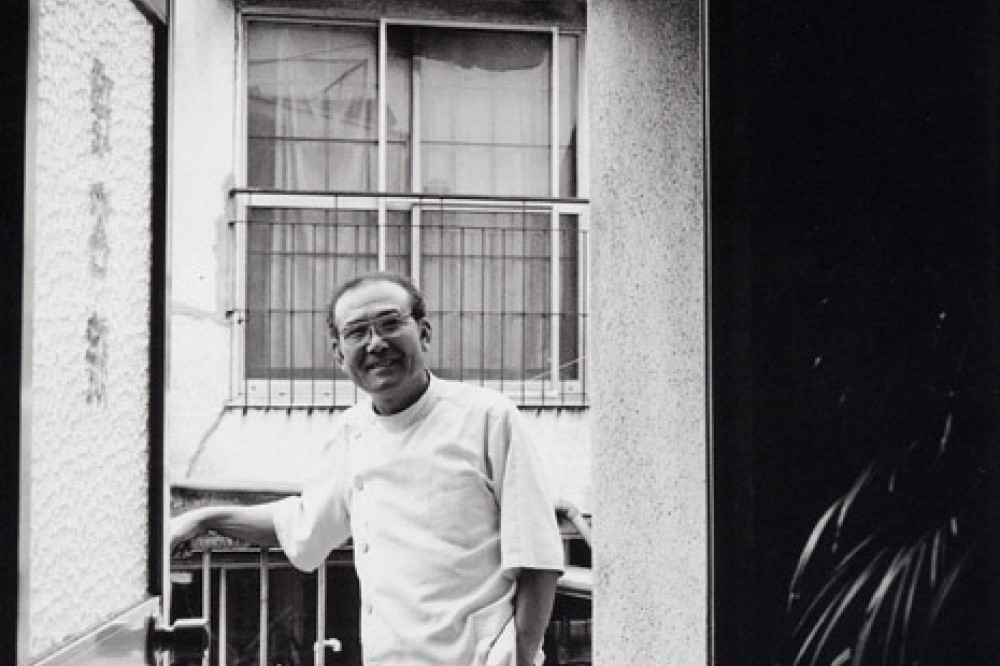

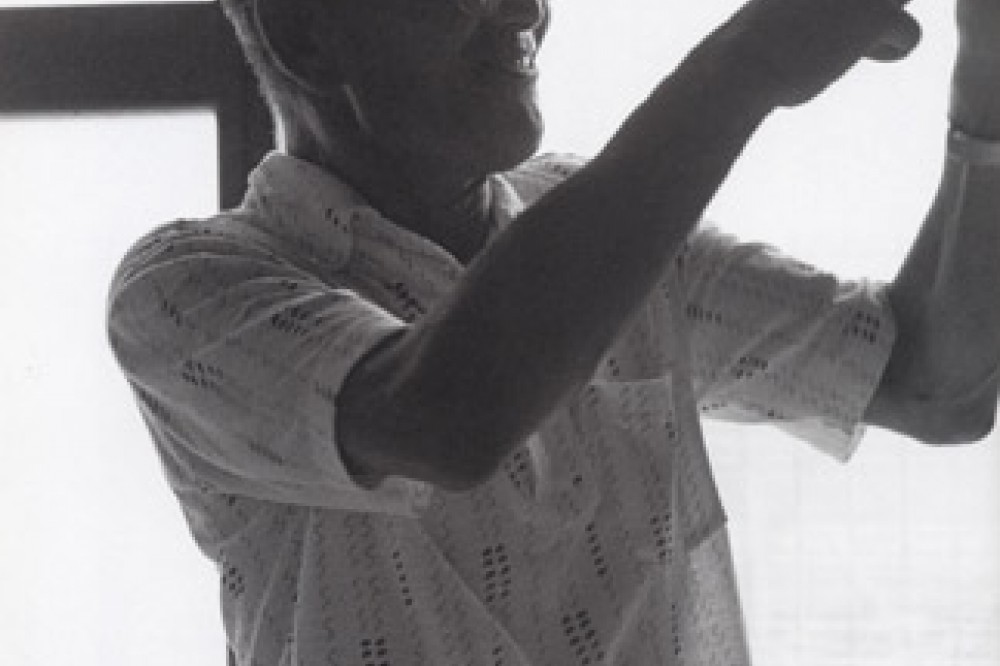

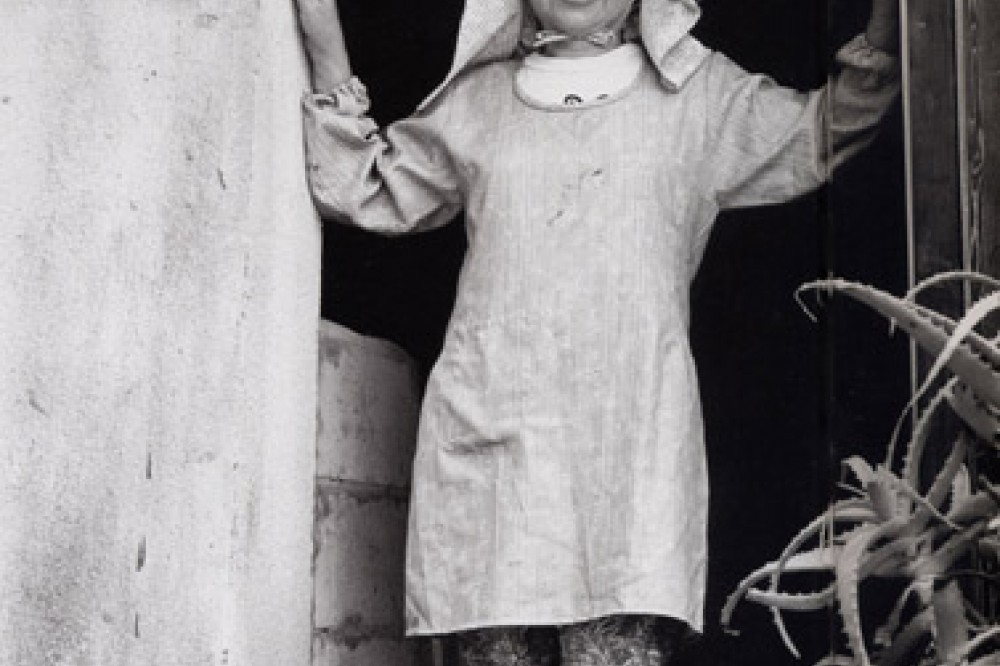

Through the camera’s finder, I was touched by the glances of the deaf and dumb, inspired by the optimism in their smiles, shaken by the view of their lives that showed, without their willing it, through their backs. There is a drama in each of them. Each made me feel he has had the strength it took to make it through, even as he shouldered everything that comes with being both handicapped and a victim of an atomic bomb.

Don ga Kikoenakatta Hitobito: The Deaf and the Atomic Bomb, available online courtesy of Bunrikaku.

A Beginner's Introduction to Deaf History

A Beginner’s Introduction to Deaf History. Ed. Raymond Lee. Feltham: BDHS Publications, 2004. OVER 4th and ETRR, HV2367 .B43 2004. Section on WW II online courtesy of Raymond Lee. 93-101.

Read the chapter “World War II”, reproduced as a PDF document with permission.

Deaf Esprit

Inspiration, Humor and Wisdom from the Deaf Community

edited by Damara Goff Paris & Mark Drolsbaugh.

Salem, OR: AGO Gifts and Publications, 1999.

with a Foreword from Marvin Miller, Editor-in-Chief of DeafNation Newspaper

- World War II in Norway by Henning Irgens

- Post-War Experiences of Henning Irgens by Henning Irgens

- Frieda and Me by Ira J. Rothenberg

A Mission in Art: Recent Holocaust Works in America

by Vivian Alpert Thompson

Excerpt about survivor David Bloch.

Thompson, Vivian Alpert. “David Bloch.” A Mission in Art : Recent Holocaust Works in America . Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1988. 20-27.

Reproduced by permission of David Bloch’s estate and Mercer University Press, Macon, GA

The Paintings

Ten Commandments Imagery

Woodcuts

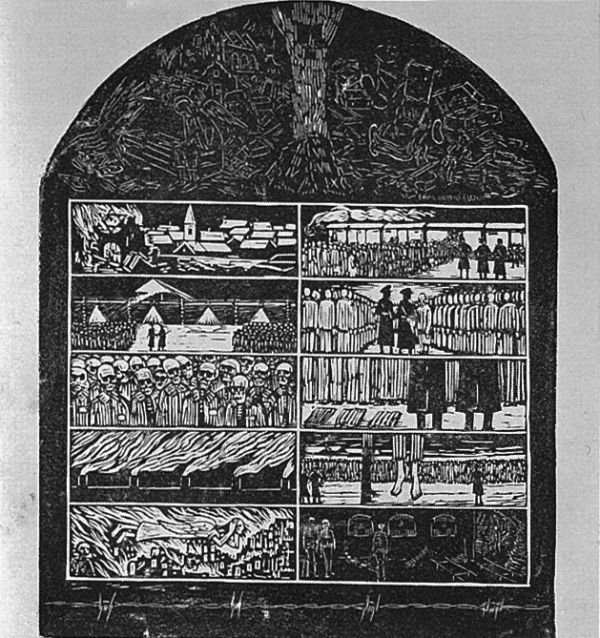

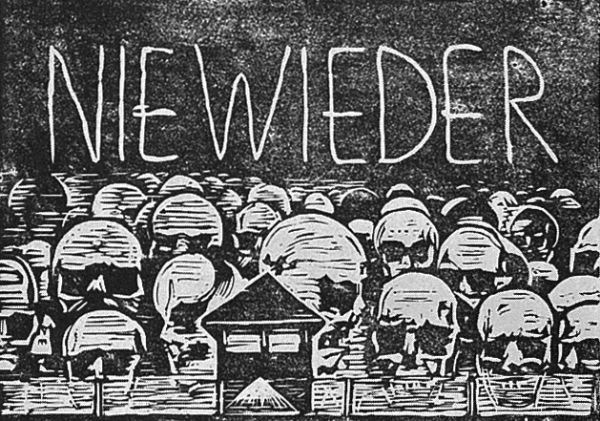

Much of the visual imagery that appears in Bloch’s paintings reappears in his woodcuts. These woodcuts demonstrate some connection to Bloch’s German background and his likely acquaintance with German Expressionism. The bold, harsh lines that give further emotional impact to the works, and the exaggerated, gouged lines of the faces hint at the influence of the German Expressionists, who would have been familiar to Bloch as a young man.

The Message

Deaf History International Conference Proceedings

Overcoming the Past, Determining its Consequences and Finding Solutions for the Present

Knock at Midnight is about Bloch’s own arrest. Seized on Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass when stores and synagogues were smashed and burned, Bloch was one of thousands of Jews who were removed from their own homes and taken off to a concentration camp. The painting is almost entirely a solid, deep, dark blue, broken only by the arrest scene that takes place in the extreme corner. The only light source comes from within the home, where the inhabitants have been jarred awake by the intrusion. Two black-coated guards with red Nazi armbands oversee the arrest. One Nazi holds a gun to the back of one victim’s head, while a second victim, also barefoot and in pajamas, is shown from the chest down as he is forced down the stairs. Two other residents of the home look on in horror. We see the work from the outside, looking in, catching only a glimpse of the scene from the doorway of the residence. We are onlookers from a distance, witness to the scene in a general sense. Although this scene may be about Bloch’s own arrest, nothing in the work indicates a specific place or person. It is generalized enough to represent the story for thousands, as the painting is meant to do. One of the invariable characteristics of Holocaust art is that it is not only highly autobiographical, but it also tends to tell the group story rather than that of one individual.

Knock at Midnight is about Bloch’s own arrest. Seized on Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass when stores and synagogues were smashed and burned, Bloch was one of thousands of Jews who were removed from their own homes and taken off to a concentration camp. The painting is almost entirely a solid, deep, dark blue, broken only by the arrest scene that takes place in the extreme corner. The only light source comes from within the home, where the inhabitants have been jarred awake by the intrusion. Two black-coated guards with red Nazi armbands oversee the arrest. One Nazi holds a gun to the back of one victim’s head, while a second victim, also barefoot and in pajamas, is shown from the chest down as he is forced down the stairs. Two other residents of the home look on in horror. We see the work from the outside, looking in, catching only a glimpse of the scene from the doorway of the residence. We are onlookers from a distance, witness to the scene in a general sense. Although this scene may be about Bloch’s own arrest, nothing in the work indicates a specific place or person. It is generalized enough to represent the story for thousands, as the painting is meant to do. One of the invariable characteristics of Holocaust art is that it is not only highly autobiographical, but it also tends to tell the group story rather than that of one individual. The transport was a nightmare that is a major theme in diaries and documentaries. In Transport Bloch shows us the loading of the trains juxtaposed against a lovely winter scene with snow-capped mountains in the distance. At first glance it is a beautiful scene, until one becomes aware of the miserable masses of people of all ages being herded into the cattle cars, their meager belongings being stripped from them. The church is a silent onlooker in the background, a reminder similar to Bernbaum’s indictment of the passivity and complacency of the church.

The transport was a nightmare that is a major theme in diaries and documentaries. In Transport Bloch shows us the loading of the trains juxtaposed against a lovely winter scene with snow-capped mountains in the distance. At first glance it is a beautiful scene, until one becomes aware of the miserable masses of people of all ages being herded into the cattle cars, their meager belongings being stripped from them. The church is a silent onlooker in the background, a reminder similar to Bernbaum’s indictment of the passivity and complacency of the church. A sharp perspective funnels the eye back into the only opening: the entrance to the camp in The Last Stop. There is no other exit. The left side is flanked by barbed wire; the rest of the scene depicts railroad tracks that recede into the distance, depositing the victims at the camp.

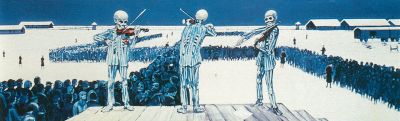

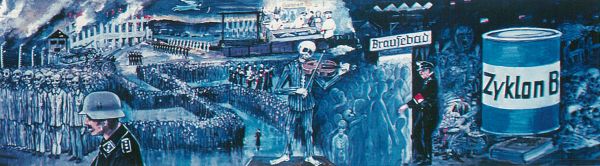

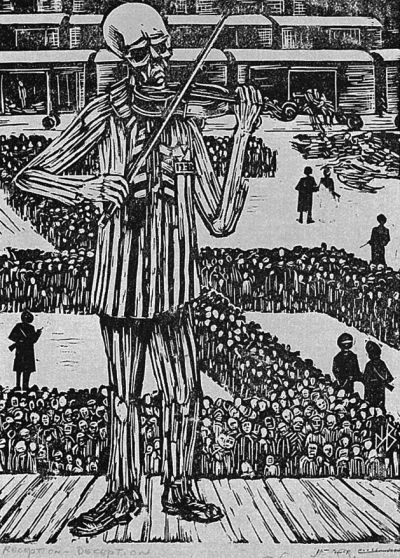

A sharp perspective funnels the eye back into the only opening: the entrance to the camp in The Last Stop. There is no other exit. The left side is flanked by barbed wire; the rest of the scene depicts railroad tracks that recede into the distance, depositing the victims at the camp. Reception Deception is a chilling work-brittle and crisp in its shades of blue against the stark whiteness of the snow-and haunting in its meaning. Three emotionless skeletal figures are playing music to accompany the newly arrived transportees being led to their deaths. The death march, with musical accompaniment, comes across as a Danse Macabre, only here the scene is played for real as the skeletons (probably human, but more dead than alive) play for the newly arrived (and soonto-be-dead) masses. As the lines move slowly, they form the shape of a huge swastika. A few faces, blue with cold and suffering, look up at the musicians in puzzlement, at a world gone mad. The landscape is stark, bare, and flat, except for some camp barracks and the now-empty boxcars off to the side.

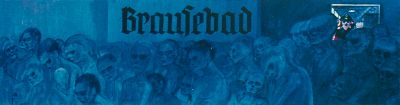

Reception Deception is a chilling work-brittle and crisp in its shades of blue against the stark whiteness of the snow-and haunting in its meaning. Three emotionless skeletal figures are playing music to accompany the newly arrived transportees being led to their deaths. The death march, with musical accompaniment, comes across as a Danse Macabre, only here the scene is played for real as the skeletons (probably human, but more dead than alive) play for the newly arrived (and soonto-be-dead) masses. As the lines move slowly, they form the shape of a huge swastika. A few faces, blue with cold and suffering, look up at the musicians in puzzlement, at a world gone mad. The landscape is stark, bare, and flat, except for some camp barracks and the now-empty boxcars off to the side. The deception also encompassed language, for the Nazis were masters at transforming seemingly innocuous words into words connoting great horror. Brausebad, meaning showers, was a euphemism for the gas chambers used to confuse the victims and to destroy even the language. The light is through the doorway, which is blocked by a Nazi guard whose face is the only natural, flesh-colored one. The victims-all ages, all sizes-are many shades of blue, their faces already numb to the horror about to occur.

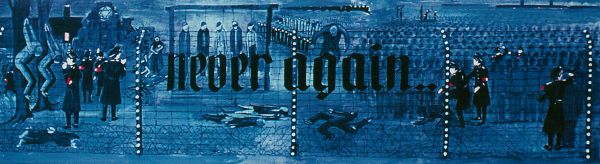

The deception also encompassed language, for the Nazis were masters at transforming seemingly innocuous words into words connoting great horror. Brausebad, meaning showers, was a euphemism for the gas chambers used to confuse the victims and to destroy even the language. The light is through the doorway, which is blocked by a Nazi guard whose face is the only natural, flesh-colored one. The victims-all ages, all sizes-are many shades of blue, their faces already numb to the horror about to occur. The perversion of language appeared vividly at Auschwitz where the entranceway was marked by a tall gate labeled “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Makes Free”). In his work by that name, Bloch superimposes the gateway over a space filled with skulls and death masks. The pathetic irony is made clear by the death masks: only through death was there freedom, for the people were murdered by overwork. The tones are a pale, whitish-blue, cold and deathly in their hues. In the lower portion of the painting is a second gateway-only this one has been barricaded with a red and white barrier so that no one can ever enter. It is Bloch’s way of saying “never again.”

The perversion of language appeared vividly at Auschwitz where the entranceway was marked by a tall gate labeled “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Makes Free”). In his work by that name, Bloch superimposes the gateway over a space filled with skulls and death masks. The pathetic irony is made clear by the death masks: only through death was there freedom, for the people were murdered by overwork. The tones are a pale, whitish-blue, cold and deathly in their hues. In the lower portion of the painting is a second gateway-only this one has been barricaded with a red and white barrier so that no one can ever enter. It is Bloch’s way of saying “never again.”

Three dominant belching smokestacks are outlined against the sky in the foreground of Death Factory. The flames from two of them visible at the top of the canvas are evidence of the intense heat beneath. Dark smoke issues forth from both the crematoria in the background, lightening as it spreads throughout the sky, which takes up almost the top two-thirds of the painting. The sky is the focal point of the painting, for the smoke contains the faces of victims, faces that merge and emerge from the smoke that carries their remains. There have been artists before who hid faces or figures in clouds (for example, Mantegna and Raphael); such an artistic device is not new. But nowhere else in art do we have the faces of hundreds of cremated victims peering at as from their death. The faces that Bloch depicts are not portraits, nor are there portraits in his other works. He is telling us not of the suffering and deaths of particular individuals, but of the endless numbers of victims of the Nazis. A barbed wire fence through which we see the darkly outlined barracks is in the foreground. The barbed wire is not merely a barrier to those inside; it is also a barrier to us as viewers. Much of the Holocaust art attempts to reinforce the inner-outer dichotomy, the sense that this was truly another world, or what David Rousset has called “l’univers concentrationnaire.”

Three dominant belching smokestacks are outlined against the sky in the foreground of Death Factory. The flames from two of them visible at the top of the canvas are evidence of the intense heat beneath. Dark smoke issues forth from both the crematoria in the background, lightening as it spreads throughout the sky, which takes up almost the top two-thirds of the painting. The sky is the focal point of the painting, for the smoke contains the faces of victims, faces that merge and emerge from the smoke that carries their remains. There have been artists before who hid faces or figures in clouds (for example, Mantegna and Raphael); such an artistic device is not new. But nowhere else in art do we have the faces of hundreds of cremated victims peering at as from their death. The faces that Bloch depicts are not portraits, nor are there portraits in his other works. He is telling us not of the suffering and deaths of particular individuals, but of the endless numbers of victims of the Nazis. A barbed wire fence through which we see the darkly outlined barracks is in the foreground. The barbed wire is not merely a barrier to those inside; it is also a barrier to us as viewers. Much of the Holocaust art attempts to reinforce the inner-outer dichotomy, the sense that this was truly another world, or what David Rousset has called “l’univers concentrationnaire.”

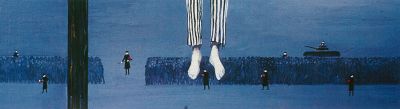

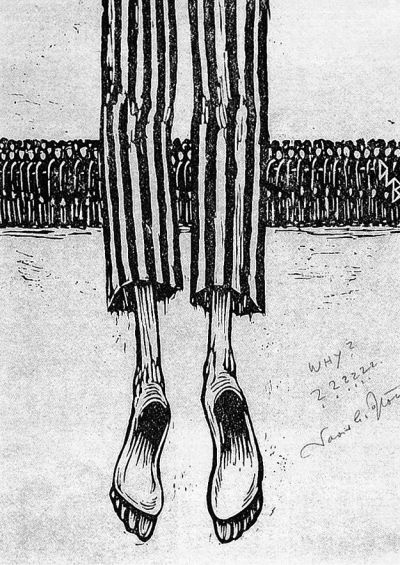

Why shows the legs of a hanged man from the knees down facing us in the foreground as a silent mass of blue inmates is forced to stand at attention to watch the spectacle. It is a stark, severe work, emphasized by Bloch’s strong horizontals and verticals. The canvas’s horizontal is reiterated by the horizontal mass of observers and then broken by the strong vertical of the two legs, the stripes of the uniform, and the vertical pole of the gallows. A few guards are positioned randomly to keep order. The bare feet and tattered pants legs make the scene more pathetic as we are forced to look at this totally undignified scene of death.

Why shows the legs of a hanged man from the knees down facing us in the foreground as a silent mass of blue inmates is forced to stand at attention to watch the spectacle. It is a stark, severe work, emphasized by Bloch’s strong horizontals and verticals. The canvas’s horizontal is reiterated by the horizontal mass of observers and then broken by the strong vertical of the two legs, the stripes of the uniform, and the vertical pole of the gallows. A few guards are positioned randomly to keep order. The bare feet and tattered pants legs make the scene more pathetic as we are forced to look at this totally undignified scene of death. No Place to Go shows shadowy figures. Both male and female, adult and child wander through a glow of light and move toward the darkness to an unknown void. The simplicity of the work enhances its impact. There is no ground line; all we see are shadows of human figures in a surreal setting. The awesome void in which they are placed is defined only by light and darkness and is all the more terrifying because of its emptiness and uncertainty.

No Place to Go shows shadowy figures. Both male and female, adult and child wander through a glow of light and move toward the darkness to an unknown void. The simplicity of the work enhances its impact. There is no ground line; all we see are shadows of human figures in a surreal setting. The awesome void in which they are placed is defined only by light and darkness and is all the more terrifying because of its emptiness and uncertainty. Left: Death-Right: Slavery refers to the selection that occurred on arrival and that continued with terrifying regularity. Those selected for hard labor received a temporary reprieve. Those picked out to die were sent to the gas chambers. Bloch shows those chosen for labor in a deeper blue; those fated to die are light blue, thin figures that diminish and recede off to the left. On the far left a sinister depiction of the showers is painted a very deep blue to make it quite clear to viewers that there can be no uncertainty about what happened to the victims.

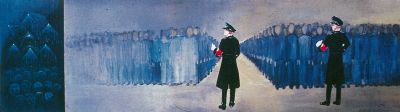

Left: Death-Right: Slavery refers to the selection that occurred on arrival and that continued with terrifying regularity. Those selected for hard labor received a temporary reprieve. Those picked out to die were sent to the gas chambers. Bloch shows those chosen for labor in a deeper blue; those fated to die are light blue, thin figures that diminish and recede off to the left. On the far left a sinister depiction of the showers is painted a very deep blue to make it quite clear to viewers that there can be no uncertainty about what happened to the victims. Dachau is where David Bloch was held captive until he was miraculously freed. As viewers we witness a roll call with the inmates’ backs to us. Bloch constructs the work so that we become part of the group; we look where they look, seeing the same endless line of victims and the black-uniformed oppressors. To erase any doubt about what this scene is, the word DACHAU, in German Gothic printing, blares out at us with the immediacy of a newspaper headline. Five folded uniforms lie on the ground; even the dead had to be accounted for and recorded.

Dachau is where David Bloch was held captive until he was miraculously freed. As viewers we witness a roll call with the inmates’ backs to us. Bloch constructs the work so that we become part of the group; we look where they look, seeing the same endless line of victims and the black-uniformed oppressors. To erase any doubt about what this scene is, the word DACHAU, in German Gothic printing, blares out at us with the immediacy of a newspaper headline. Five folded uniforms lie on the ground; even the dead had to be accounted for and recorded. Another work describing the daily roll call is Roll Call for All. Three neatly folded uniforms of recently deceased inhabitants rest on the ground. It is essentially a portrait of three dead men, their numbers of identification and now empty clothing being all that we know of them. The rest of the work consists of legs-legs of those who can still stand at attention, in contrast to the casual stance of an SS man. The ground is white with strong shadows being cast by the legs and by the guard.

Another work describing the daily roll call is Roll Call for All. Three neatly folded uniforms of recently deceased inhabitants rest on the ground. It is essentially a portrait of three dead men, their numbers of identification and now empty clothing being all that we know of them. The rest of the work consists of legs-legs of those who can still stand at attention, in contrast to the casual stance of an SS man. The ground is white with strong shadows being cast by the legs and by the guard. Bloch uses the image of the Ten Commandments frequently in his works as an indictment of those who ignored the laws of God. In The Powers That Be a large tablet of the Ten Commandments faces us. Men with different kinds of headdresses representing the academic world (mortarboard), religious powers (miter), and political and economic powers (crown and top hat) have their backs to us, to the Ten Commandments, and to the fragments of Jewish civilization scattered in the foreground. Books are shown in disarray; not only has man turned his back on the laws that can help us to live decently, but also on the great literature of the world-literature that for centuries has sought answers for the great problems of life.

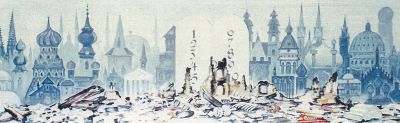

Bloch uses the image of the Ten Commandments frequently in his works as an indictment of those who ignored the laws of God. In The Powers That Be a large tablet of the Ten Commandments faces us. Men with different kinds of headdresses representing the academic world (mortarboard), religious powers (miter), and political and economic powers (crown and top hat) have their backs to us, to the Ten Commandments, and to the fragments of Jewish civilization scattered in the foreground. Books are shown in disarray; not only has man turned his back on the laws that can help us to live decently, but also on the great literature of the world-literature that for centuries has sought answers for the great problems of life. The mockery and desecration of the Ten Commandments is the blunt and disturbing message of The Churches. The tablets are again in the center of the work; a burned-out fragment of a building is outlined against the large tablets. Among the debris littering the foreground of the painting are a menorah, Torah scroll, and rimmon, the pomegranate-shaped decorative tops of the Torah. The skyline is a visual history of European church architecture, including Russian Orthodox, the twin spires of a Gothic cathedral, a dome similar to Saint Peter’s (Renaissance), German towers, and a neoclassical church. They form a vast panorama of the churches of Christendom. The churches stand silent and distant behind the Ten Commandments, ignoring the destruction and havoc, removed and detached from the great suffering. Although erect and imposing, these buildings are a mockery when viewed against the Ten Commandments.

The mockery and desecration of the Ten Commandments is the blunt and disturbing message of The Churches. The tablets are again in the center of the work; a burned-out fragment of a building is outlined against the large tablets. Among the debris littering the foreground of the painting are a menorah, Torah scroll, and rimmon, the pomegranate-shaped decorative tops of the Torah. The skyline is a visual history of European church architecture, including Russian Orthodox, the twin spires of a Gothic cathedral, a dome similar to Saint Peter’s (Renaissance), German towers, and a neoclassical church. They form a vast panorama of the churches of Christendom. The churches stand silent and distant behind the Ten Commandments, ignoring the destruction and havoc, removed and detached from the great suffering. Although erect and imposing, these buildings are a mockery when viewed against the Ten Commandments. The Ten Commandments themselves have turned to rubble in The Black Corps. The Black Corps was a term for the SS who wore black uniforms with the skull and crossbones on their caps and jackets. The tablets have shattered; a red swastika is slashed across them like graffiti on a wall. It is a death march: the guards black, the victims pale, the architectural landscape of Germany mute and distant in the background.

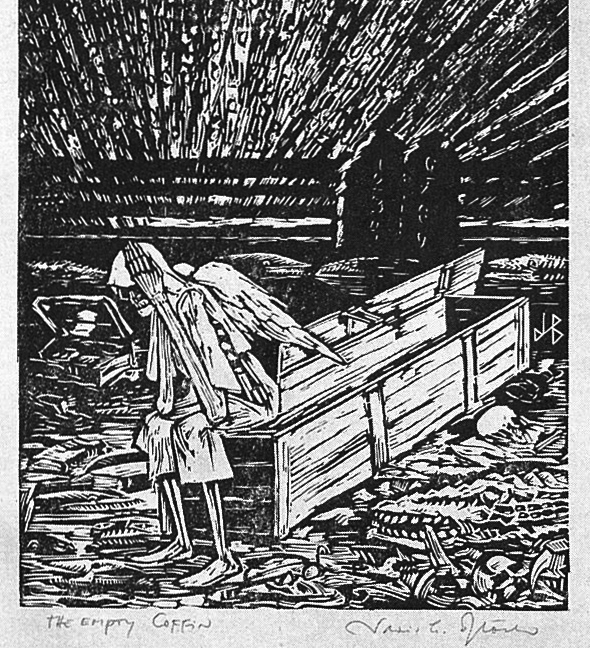

The Ten Commandments themselves have turned to rubble in The Black Corps. The Black Corps was a term for the SS who wore black uniforms with the skull and crossbones on their caps and jackets. The tablets have shattered; a red swastika is slashed across them like graffiti on a wall. It is a death march: the guards black, the victims pale, the architectural landscape of Germany mute and distant in the background. The Ten Commandments are finally destroyed in The Empty Box, where the fragmented tablets lie on the ground near an empty coffin. The Angel of Death again mourns for the deaths that were not his to take. A coffin is empty; the body is not where it should be, not having been buried or mourned in the usual way. The script on the tablet in this painting is in Hebrew; in earlier works, it is in Roman and Arabic numerals. Bloch intentionally shows the laws in different letters and numbers to stress the international and historical acceptance of the Ten Commandments as an appropriate and essential code of conduct.

The Ten Commandments are finally destroyed in The Empty Box, where the fragmented tablets lie on the ground near an empty coffin. The Angel of Death again mourns for the deaths that were not his to take. A coffin is empty; the body is not where it should be, not having been buried or mourned in the usual way. The script on the tablet in this painting is in Hebrew; in earlier works, it is in Roman and Arabic numerals. Bloch intentionally shows the laws in different letters and numbers to stress the international and historical acceptance of the Ten Commandments as an appropriate and essential code of conduct. Several of the works superimpose a very large foreground figure or image against a detailed backdrop with a great deal of activity. One example is Reception Deception (essentially a detail of the painting of the same name), which has a skeletonlike figure with black sockets for eyes in a camp uniform (no. 1938) playing the violin on a platform. Behind him is a reception scene with the boxcars being unloaded, dead bodies piled up, and the remainder of the people herded into long lines forming the shape of a swastika. In the background, boxcars are lined up at least three tracks deep, as if to infinity.

Several of the works superimpose a very large foreground figure or image against a detailed backdrop with a great deal of activity. One example is Reception Deception (essentially a detail of the painting of the same name), which has a skeletonlike figure with black sockets for eyes in a camp uniform (no. 1938) playing the violin on a platform. Behind him is a reception scene with the boxcars being unloaded, dead bodies piled up, and the remainder of the people herded into long lines forming the shape of a swastika. In the background, boxcars are lined up at least three tracks deep, as if to infinity. Another image that Bloch uses is that of a hanged man, shown only from the back and from the knees down, superimposed against a lineup of faceless, anonymous inmates who were most likely forced to witness the hanging at a roll call. The man’s pants legs are tattered, the ankles gaunt and emaciated, anti the feet hang lifelessly. The black on white emphasizes the starkness of the work.

Another image that Bloch uses is that of a hanged man, shown only from the back and from the knees down, superimposed against a lineup of faceless, anonymous inmates who were most likely forced to witness the hanging at a roll call. The man’s pants legs are tattered, the ankles gaunt and emaciated, anti the feet hang lifelessly. The black on white emphasizes the starkness of the work.

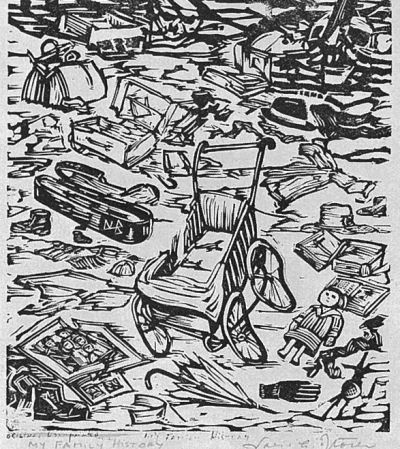

Remnants of family life are scattered in My Family History, a work that features a shattered family picture, a broken, open violin case, a doll, and in the center a broken baby buggy-all mournful reminders of the individuals whose lives were lost. In the background an arm rises up imploringly from out of the ground.

Remnants of family life are scattered in My Family History, a work that features a shattered family picture, a broken, open violin case, a doll, and in the center a broken baby buggy-all mournful reminders of the individuals whose lives were lost. In the background an arm rises up imploringly from out of the ground.