Edmund D. Fountain

Edmund D. Fountain

New Orleans photojournalist Edmund D. Fountain is an award-winning editorial photographer specializing in portraiture and documentary storytelling.

He grew up in Houston, got a degree from Rochester Institute of Technology and spent nearly a decade as a staff photographer for the Tampa Bay Times (formerly St. Petersburg Times) covering local, national and international news. He has covered stories in the West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Mexico, Panama and all over the United States.

In 2010 Fountain was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize along with two reporters for a series of stories examining a century of abuse at a Florida reform school. These stories ultimately helped shut down the school and sparked ongoing exhumation work to identify the remains of children buried in unmarked graves on the school’s campus. The remains of several children have since been returned to their families.

He is a recipient of the Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma and the Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism. His photographs have been honored multiple times by the National Press Photographers Association, the Society for News Design,The Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, Best of Photojournalism and the Florida Society of News Editors. A selection of his photographs reside in the permanent collection of the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts.

Biography text taken from Fountain's portfolio website.

2010 Finalist

Local Reporting

"For dogged reporting and searing storytelling that illuminated decades of abuse at a Florida reform school for boys and sparked remedial action." - Pulitzer Board

Fountain was the photographer for the series of stories that received finalist honors. He worked with St. Petersburg Times writers Ben Montgomery and Waveney Ann Moore.

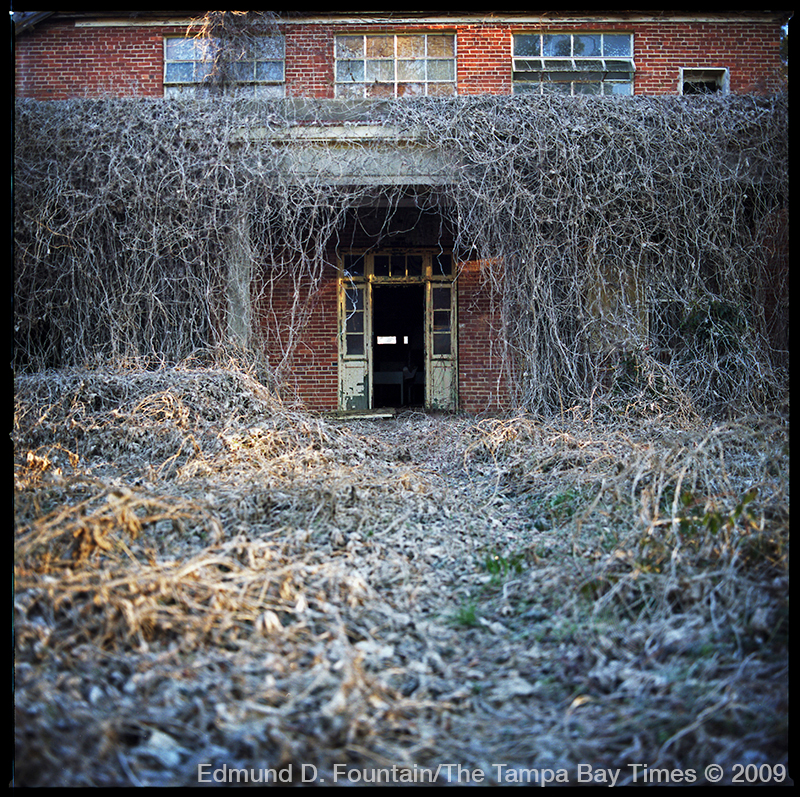

A cottage on the former campus of the Florida School for Boys is overgrown with vines. The building still contains bunks, mattresses and messages from children who lived within its walls. This building would have been part of the No. 2 campus, or black campus, at the school. Taken March 18, 2009.

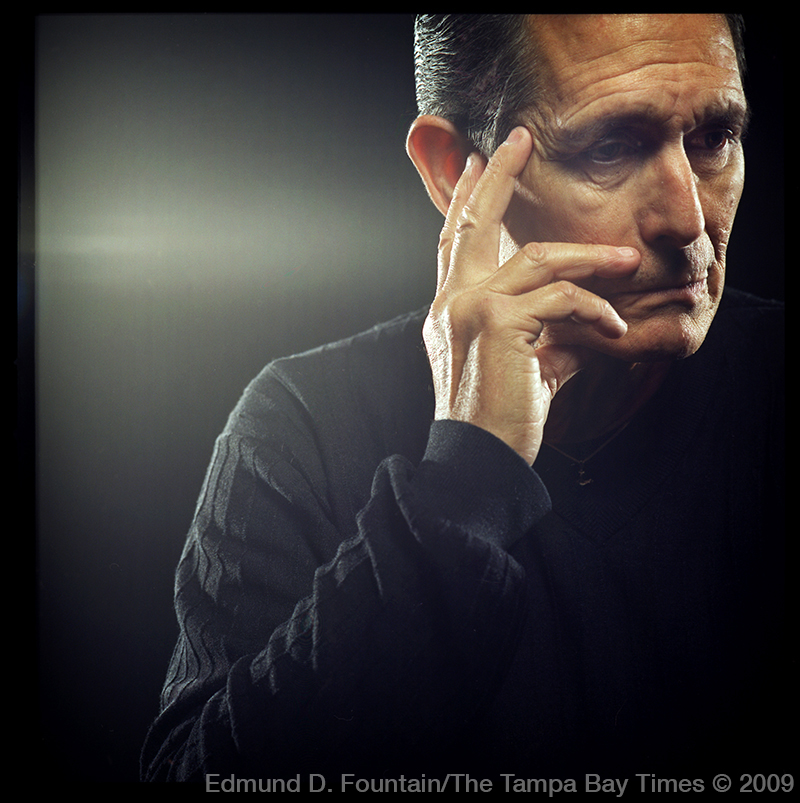

Aaron Burns, right, holds his head in his hands during a meeting at the Serenity House halfway house in DeLand where he currently lives. In the twenty years that have passed since his time at Dozier, he has been to prison four times. Every time he was released, he told himself that he would stay out of trouble, but he never managed to stay on the straight and narrow. This time he thinks things will be different. Taken Oct. 21, 2009.

In the woods not far from the current Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys is a small cemetery with 31 unmarked graves. Some think the bodies of children murdered by guards are buried in the cemetery. Some of the graves can be attributed to students killed in a 1914 fire, others to a flu epidemic that swept the campus. Even if all of the crosses can be matched with names, there are another 50 boys who went into the custody of the school who are unaccounted for.

Dick Colón, 65, of Baltimore, displays scars from beatings he received as a child at the Florida School for Boys. Colón said he thinks he received more than 250 lashes total from the staff of FSB. He still carries the emotional scars of witnessing a child die after being stuffed into an industrial dryer. He said he knew the right thing to do was to help the child, but was too afraid the staff might stuff him in the dryer himself if he intervened. "To this day I'm tormented by it," he said. "It really bothers me that I didn't have the courage to walk over there and open up the door to that dryer and pull that kid out of there." Taken March 21, 2009.

Manuel Giddens, 64, of Fort Meyers, thinks that his time at the Florida Industrial School for Boys irrevocably altered his life. "If it wasn't for that period of time, I would have took over my father's religion," he said. "I was born to be a pastor and it didn't happen. I was born to take over the mission, and I turned and went the other way, and now it's too late to do that. Marianna destroyed me."

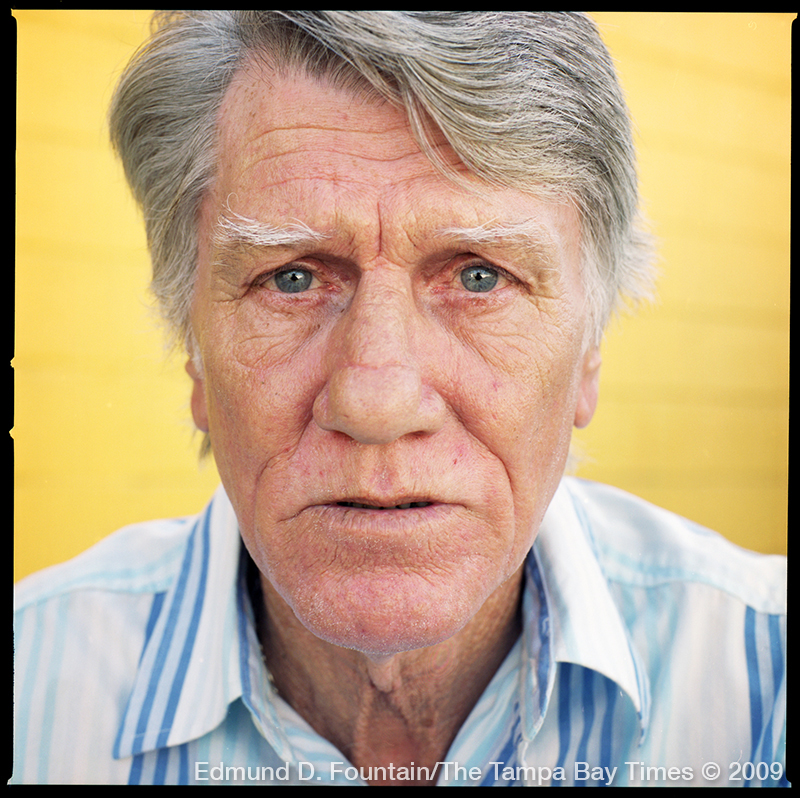

Donnie Shoffner, 63, ran away from the Florida School for Boys with Michael Smelley and two other boys in 1966. They were all caught. "Mike got tired of running," Shoffner said. "They got him first." He remembers the guard who caught him telling him he might get shot if he tried to run away. He was taken back to the school and whipped 45 times. He said he saw Smelley the next morning, and he was having trouble walking. He was moved to the infirmary. Shoffner never saw Smelley alive after that. Taken May 5, 2009.

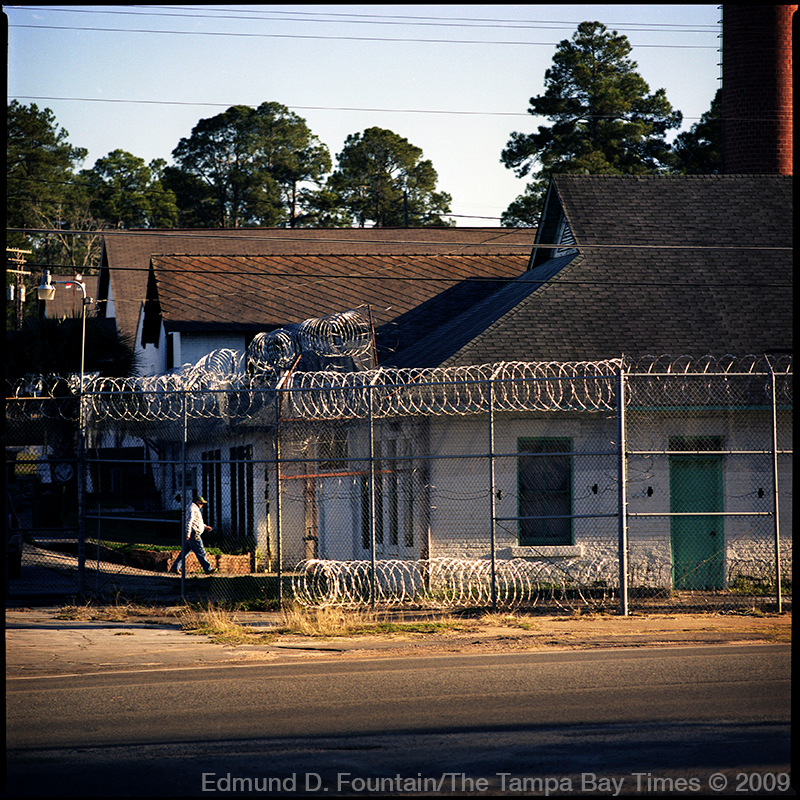

The Florida School for Boys did not have fences in the 1950s and 1960s. As a result, boys would frequently run away to escape the deplorable conditions of the school and abuse from the staff. They were usually caught by guards, dogs or townspeople. Former wards of the school remember being forced to carry the dogs back to the campus after being caught while congratulating the dogs for finding them. Now renamed the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, the facility is ringed with chain link fence and razor wire.

Stu Krueger worked on Wall Street and now runs a credit repair business. The 67-year-old tried to run away from the Florida School for Boys with another boy and was caught. They were both beaten, but the other boy went first. While he was listening, Krueger picked up a pebble and began nervously twirling it in his fingers. Fifty years and five marriages later, he still keeps a pebble in his pocket. "Fifty f***ing years," he said.

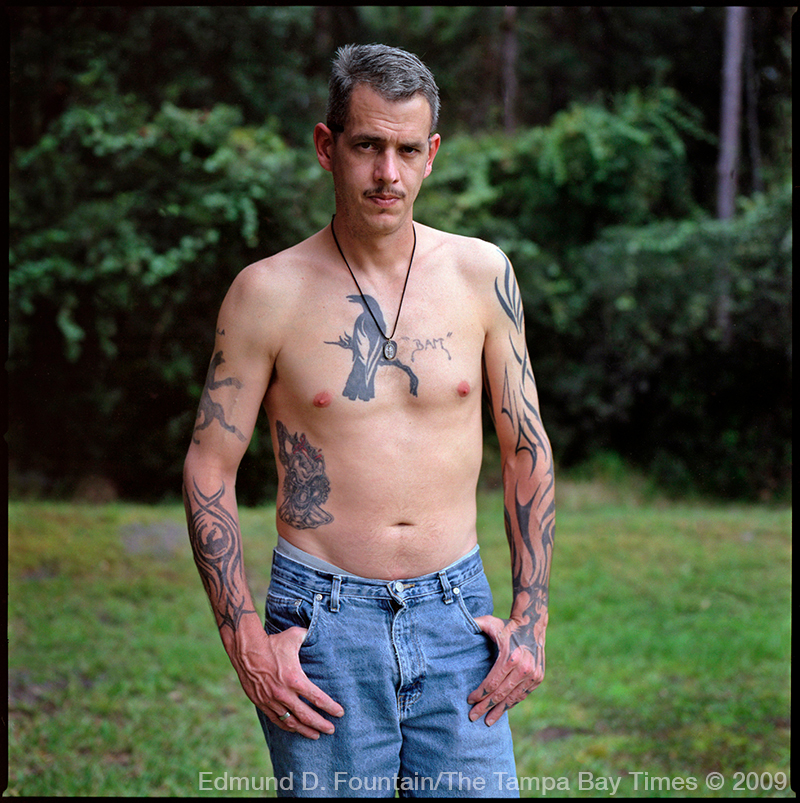

"Marianna left scar tissue," said Aaron Burns, who was first sent to the Dozier School for Boys at age 15. "It was a place where you were made to feel like you were worthless. They'd tell you, 'Your parents don't love you. Nobody loves you.'" The tattoos now covering his torso and arms are testament to a life spent in and out of prison. In the 20 years that have passed since his time at Dozier, he has been to prison four times. Taken Oct. 21, 2009.

"I wanted to go down there and kill them men,'' said Carol Smelley, 82, right, of the staff at the Florida School for Boys who she credits with killing her son Michael in 1966. She and her husband Terry, have been silent about their son's death for decades, giving up hope that it would ever be looked into. Taken on May 5, 2009.

Derek Gavin, of Wildwood, stands of a portrait on Dec. 3, 2009. Gavin went to Dozier three times, and credits learning how to game the system as being the only reason he got out. "I made them think I was rehabilitated," he said. Gavin still remembers guards bringing him marijuana. After getting out of Dozier, Gavin served 12 years in prison. He has been out for six now.

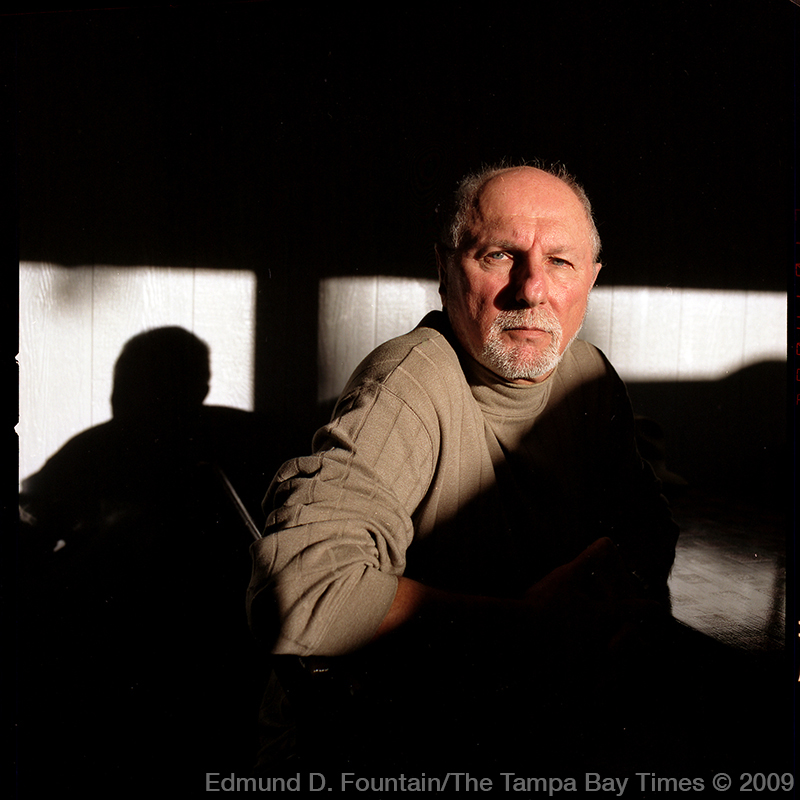

Marshall Drawdy, 70, of Jacksonville, spent 17 months at the Florida Industrial School for Boys between 1956-57 for picking up a boy's bicycle and throwing it in a ditch half a block away. "When I got out, I went to work you might say," he said. "I proceeded to plunder as you might say. I robbed, I stole ... I never amounted to nobody." Drawdy says that he cannot forgive those who beat him at the school. "The whole place was just a damn hell hole and I can't forget it. They need to be in hell." Taken March 21, 2009.

Roger Kiser began writing about his experiences online and soon other people who were searching for information about the Florida School for Boys began contacting him and sending their own stories. Kiser still has problems with hugs and with his temper. He thinks his treatment at the school is the root of his problem. He recalls a time when his daughter stole a piece of pie. "I beat the shit out of her," he said.

The bathroom of a cottage on the former Number Two campus of the Florida Industrial School for Boys. It is in this room that children would have tried to pick their underwear back out of their flesh after being beaten by the school's staff while letting water run over their wounds. When in operation in the 1950s and '60s, these buildings would have housed the school's Black population. Men who were incarcerated at the school during those decades claim to have been horribly abused both physically and sexually at the hands of the staff that was charged with reforming them. Taken March 18, 2009.

Matthew Schroeder, 18, of Crawfordville, was born with cystic fibrosis, a condition which causes his lungs and pancreas to secrete thick mucus which blocks passageways in his body. He was sentenced to Dozier after running with the wrong crowd and getting busted for pot, burglary and larceny. Schroeder claims he was sick for the first 65 days he was at Dozier and his illness was dismissed by the staff. Schroeder was told the only thing they could give him to help was Malox.

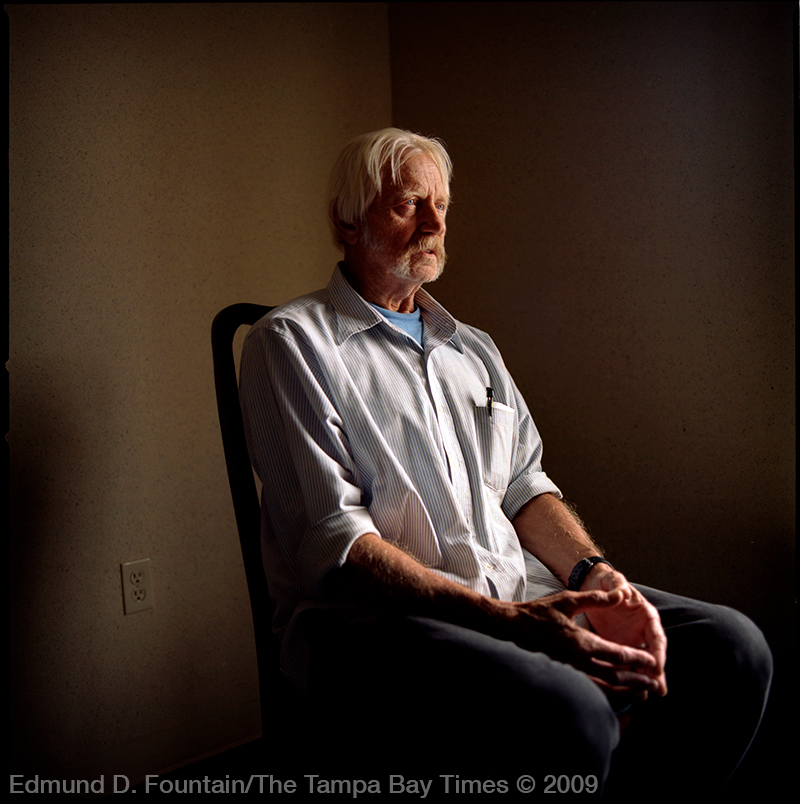

George Goewey, 62, of St. Petersburg doesn't understand why he was sent to the Florida Industrial School for Boys in 1957 after his parents divorced. His father, Edgar Goewey, was a Pinellas Patrol Chief and an abusive alcoholic. Goewey was sent a second time for skipping school. Since then, he has been arrested 38 times and has never married. Taken Feb. 25, 2009.