Home Page

- RIT/

- Office of the Provost

In addition to academic planning and curriculum development, the provost champions continued excellence in student-centered learning, teaching, research, and scholarship.

4

Global Campus Locations

In addition to Rochester, N.Y., RIT has campuses in Croatia, Dubai, and Kosovo.

95%

Outcome Rate

For each of the past three years, 95 percent of RIT graduates enter either the workforce or graduate study within six months of graduation

43rd

“Best Value Schools”

U.S. News & World Report, 2026

100

Countries

Students from all 50 states and more than 100 countries attend RIT.

Celebration of Teaching and Scholarship

Outstanding Undergraduate Scholar Awards

Academic Affairs News

-

February 6, 2026

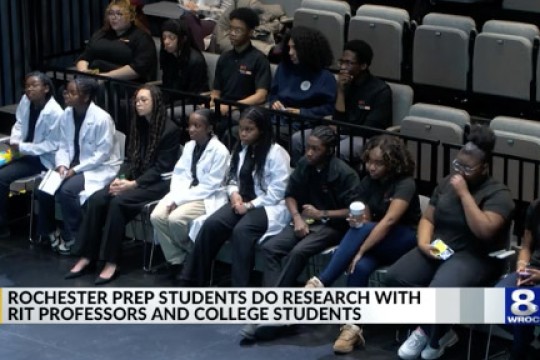

Rochester Prep students present research findings at RIT

WROC-TV speaks to Donna Burnette, executive director of the K-12 University Center, about the importance of exposing youth to collegiate opportunities.

-

February 6, 2026

ArtEx students find community by leaning into creativity

ArtEx creates opportunities for students outside of RIT’s College of Art and Design to participate in creative and collaborative experiences by granting special access to engage with the studios, resources, and expertise available within the School for American Crafts and School of Art.

-

February 5, 2026

Co-op course helps students break into competitive industries

The Independent Professional Development course was developed last year to reflect fluctuations in the current job market and to support students who, despite their best efforts, have not yet secured co-ops.

-

January 30, 2026

Mathematical modeling alumnus wins early career award

RIT alumnus Adam Giammarese’s work in chaos theory has earned him the Edward N. Lorenz Early Career Award, an annual recognition by the publication Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science.

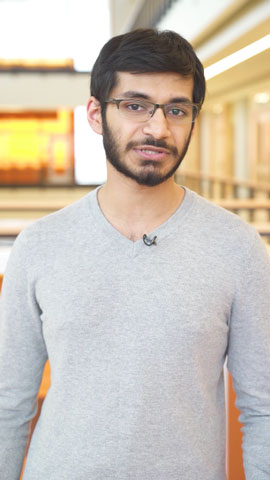

Faces of RIT

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Architecture Is Awesome

Blair BensonArchitecture M.Arch.When Blair changed careers she realized that it is never too late to pursue your passion. Now she embraces the collaborative nature of the design process, combining functionality, aesthetic appeal, and responsible practices in her architectural work.

-

Where Science Meets Art

Zayneb JaffPre-health StudiesMetals and Jewelry DesignStudying health studies has helped Jaff develop her logic and analytical skills. Adding a dual major in metals and jewelry design will prepare her well for medical school, where today's doctors must be both knowledgeable and innovative in their approaches to patient care.

-

Stepping Up

Ashley KosakMechanical EngineeringIt might be just a stool, but it represents more than reaching equipment in the Machine Shop. It’s a symbol of the heightened awareness and inclusivity of women in engineering at RIT. After graduation, Kosak wants to influence change by helping women pursue careers in engineering.

-

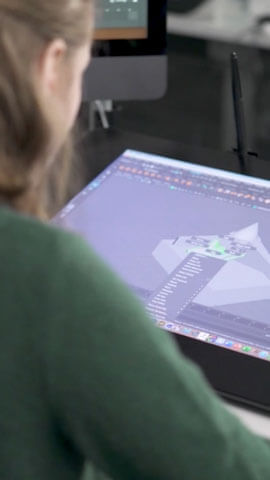

Merging Past and Present

Devin Klibanow3D Digital DesignRIT's Cary Graphics Art Collection allows students to view printing styles and graphic art from thousands of years ago. In order to preserve these artifacts, Klibanow is working with other students and faculty to create a virtual viewing experience.

-

-

-

-

-

Relationships Are Key to Success

Jess Sudol '06VP/Civil Dept. Manager - Passero AssociatesBuilding relationships and honing communication skills are crucial skills for success in any field. Passero Associates has recognized the collaborative nature of RIT students. They continue to hire RIT students and graduates for their dynamic interpersonal skills as well as their knowledge.

-

Streaming Worldwide

Nate BellaviaFilm and AnimationRIT’s student-run radio station broadcasts to the Rochester community and streams worldwide. Bellavia, WITR’s music director, appreciates that RIT has a place where people who love music can bond over their passion and share that connection over the airwaves.

-

-

Biodegradable Packaging

Carlos Diaz AcostaAssociate ProfessorDiaz Acosta's research in sustainable packaging led his class to a biodegradable solution. Developing corn-based packaging is not only being used to counteract the amount of food waste going into landfills, but also making the world a more sustainable place.

-

-

-

-

Innate Happiness

Amanda DeVito EMBA '19Vice President of Client Engagement, Butler/Till MediaHappiness of employees and driving business outcomes are DeVito's main focus at Butler Till Media and Communications. Knowing all the work and energy she puts into driving a client's business is satisfaction in itself.

-

Creating a Balanced, Equal World

Remy DeCausemakerCommunications and Media TechnologyPublic PolicyOpen source software is integral to building a movement toward equality. For DeCausemaker, that meant creating a degree program in the School of Individualized Studies that targeted the specific areas of expertise he needed to craft the career path he wanted.

-

-

Connecting Kids to Science

Devon M ChristmanPhysicsOver the summer, Christman taught a workshop called “Experiments in Science” to a group of children from RIT’s Kids on Campus program. By helping to change their perspectives on who and what a scientist is, Christman is shaping the minds of tomorrow’s scientists.

-

-

-

-

-

-

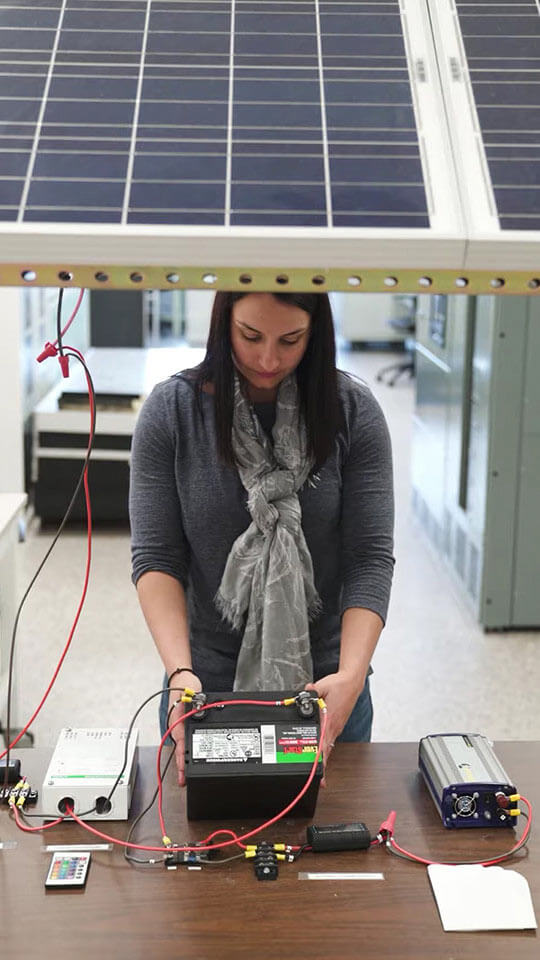

Engineering Better Solutions

Poornima PadmanabhanAssistant ProfessorProfessor Padmanabhan’s students engage in hands-on research experiences that help build a better future through the creation of advanced complex materials that can solve problems in solar energy, health care, agriculture, and more.

-

-

-

-

Visual Exploration

Fred Beam '85As outreach coordinator for Sunshine 2.0, a theater group at RIT's National Institute for the Deaf, Beam and his troupe provide performances and activities for deaf and hard-of-hearing children and adults that highlight the fields of deaf culture, literacy, and STEM.

-

-

-

-

Giving a Voice to a Community

Tianna Manon '15CommunicationAs an alum of the journalism program, Manon has put into practice the storytelling platforms and opportunities She took advantage of at RIT. Today, Manon serves as editor-in-chief of Open Mic Rochester, an online magazine that gives a voice to Rochester’s black community.

-

-

Online Face-Off

Evan HirshComputer ScienceTrading gloves and helmets for a monitor and a mouse has ushered in a new era in sports: competitive, organized gaming. By mirroring professional eSports, the RIT eSports team pursues competitive gaming at the highest possible level, rivaling the excitement of traditional sports teams.

-

-

Advancing Neurotechnology

Harrison CanningInnovation Science in NeurotechnologyThe School of Individualized Studies enabled Canning to create a degree that combines studies in computer science, business, and neuroscience so he can build a business that can mass produce brain-computer interfaces to help people with disabilities.

-

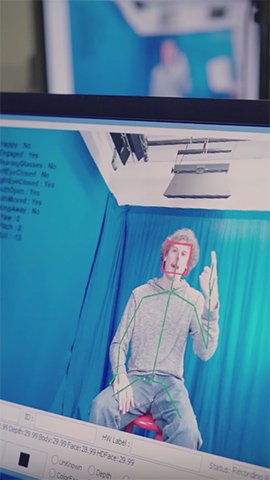

Improving Human-computer Interactions

Matt HuenerfauthProfessorImproving interactions with online platforms for those with disabilities is the ultimate goal behind Huenerfauth’s research. By training designers to create and develop more accessible websites and mobile networks, a wider audience can connect to and benefit from these technologies.

-

Making a Positive Impact

Katherine DuffySociology and International RelationsShe’s a professional ballet dancer and a humanitarian who spends her free time volunteering at a children’s home in Haiti. Duffy created a degree program in the School of Individualized Study so she can one day establish a non-profit of her own.

-

Beyond Human

Jessica WegmanPsychology MajorSeeing the world through the eyes of a different species is just one way we connect with the world around us. Through faculty-led research, Wegman is working to improve the quality of life for North American River Otters by studying their visual perception.

-

Eye on the Prize

Lily LautenschlagerBiomedical Photographic CommunicationsLautenschlager's passion for helping others drew her to a co-op opportunity in the medical science field. Through hands-on experience studying the eye, Lily has secured a part-time job while she continues her education at RIT.

-

-

-

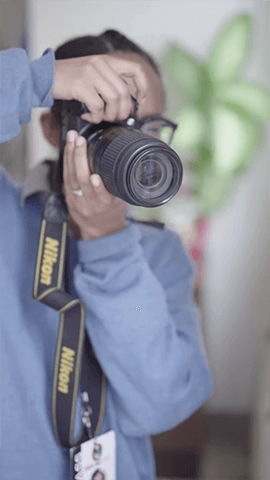

Learning to Learn

John Myers '83PhotographyFor Myers, who has traveled the world to photograph people and places, RIT was key to preparing him to adapt to an ever-changing industry. The skills he honed as a student – curiosity, responsibility, communication skills – have enhanced his decades-long career as a photographer.

-

Expanding ASL

Tina Goudreau CollisonProfessor of ChemistryA complicated vocabulary and a lack of dedicated signs in American Sign Language makes Organic Chemistry a challenge for deaf and hard of hearing students. Collison worked with interpreters to develop new ASL signs, leading to profound learning improvements for her students.