RIT scientists receive grant to expand work on a sign language lexicon for chemistry

A team of four scientists is working to make chemistry more accessible for deaf and hard-of-hearing students

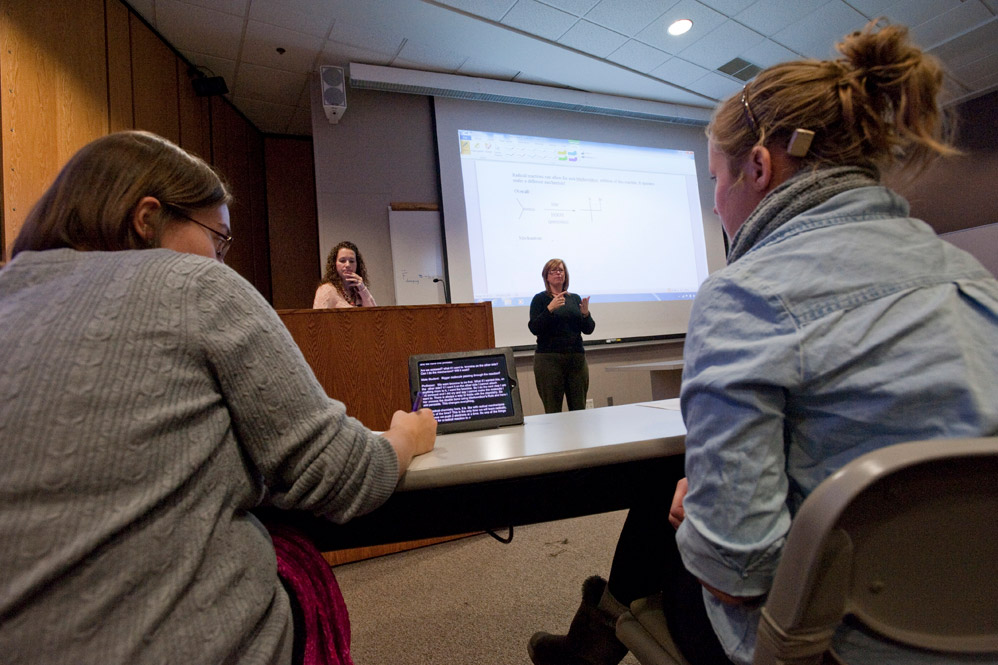

Mark Benjamin/NTID

Professor Christina Goudreau Collison is part of a research team that received a large National Science Foundation grant to continue developing a descriptive sign language lexicon to make chemistry easier for deaf and hard of hearing students.

A team of scientists at Rochester Institute of Technology will expand its work after receiving a large grant from the National Science Foundation to make chemistry more accessible for students who rely on American Sign Language interpreters in class.

Christina Goudreau Collison

Christina Goudreau Collison, professor in the School of Chemistry and Materials Science; Jennifer Swartzenberg, senior lecturer in the National Technical Institute for the Deaf’s Department of Science and Mathematics; Lea Michel, professor in the School of Chemistry and Materials Science; and Pepsi Holmquist, visiting assistant professor in NTID’s Department of Science and Mathematics, have been awarded nearly $380,000 for their proposal to transform chemistry for deaf and hard-of-hearing students via the design, implementation, and evaluation of a descriptive sign language lexicon.

The work started years ago when Swartzenberg was learning ASL. When she visited classrooms, she noticed that interpreters had to do a lot of fingerspelling to communicate technical terms. Upon further investigation, Swartzenberg realized that deaf students’ grades were lower than the hearing students’, indicating a language barrier. Swartzenberg had taken Goudreau Collison’s classes in the past and was familiar with how she used body movements to help explain terms. The pair decided to work together to find a solution.

Pepsi Holmquist

A group was formed and the initial work began. A team worked to identify organic chemistry terms, and a process evolved where deaf students created signs in collaboration with Goudreau Collison and Swartzenberg to ensure they had scientific clarity. Once they agreed on the signs, other ASL users reviewed them, and videos were created that taught the chemistry-specific signs.

Now, years after the initial implementation, there is evidence supporting the effectiveness of their efforts. Tracking one specific exam in her class, Goudreau Collison found that prior to the group’s work, deaf students were scoring below the class average. After creating and teaching the new chemistry signs, working with interpreters, and creating peer-led workshops, interpreter-dependent students were now performing above exam average.

The strategic methodology of establishing the new signs with input from students, scientists, and interpreters has proven beneficial for all and made the initial project successful.

“The signs need to be descriptive and help to understand the concept in addition to just telling what the word is,” said Goudreau Collison. “That’s where the collaboration comes in, because you really need the content and the understanding of the meaning behind the word, as well as the understanding of how a sign is going to work best for all students.”

Lea Michel

With the NSF grant, the scientists will continue the work in completing a comprehensive set of STEM signs for concepts and terms in general chemistry and biochemistry.

“This project is something that is incredibly complicated,” said Holmquist, who is deaf. “Going into the nuance and details of general chemistry and biochemistry, it can be very challenging to come up with an iconic sign that’s going to include all of the overlapping ideas that show up in our vocabulary with minimal loss in translation between English and sign language.”

To illustrate the complexity of this project and how difficult it may be to choose a suitable sign for a concept, Holmquist explained that the sign for electron is also a sign that she uses for monomer. In science, these two things have very different meanings. For students using sign language in science classes, whether the professor is referring to an electron or a monomer is crucial for the student to fully understand the lesson.

“We’re trying to look at areas where language overlaps and take that into consideration,” added Holmquist. “The goal is to minimize confusion. Sometimes you can’t use just one sign for one concept and be done with it. You need to have a selection of two or three signs for that concept.”

Jennifer Swartzenberg

Goudreau Collison and Swartzenberg led the initial research team (named the Sign Language Incorporation in Chemistry Education [SLICE]), and recruited Michel and Holmquist to expand the project. The SLICE team was recognized in June 2022 with the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Inclusion and Diversity Prize.

The work doesn’t stop when terms are identified and signs are chosen. The team plans to disseminate the new lexicon to deaf and hard-of-hearing students as well as to interpreters and chemistry faculty. In the future, the researchers plan to have workshops for faculty, staff, and interpreters to show the signs and their usefulness.

“I think it’s the key to learning for everybody,” said Goudreau Collison. “Sign language has universal design opportunities that can be leveraged for accessibility for many more learners of chemistry, for example, English as a Second language (ESL) students and other neurodiverse learners. I think it’s going to help a lot of people in many ways.”

Furthermore, giving deaf and hard-of-hearing students accessibility to science, in general, opens more doors for students to get involved in STEM programs and careers. Professors involved in the study have already seen an increase in deaf students in their research labs.

“This project is so exciting for me,” said Holmquist. “I know it’s going to make a huge difference and give deaf people options that they didn’t even know they have. I didn’t think it was possible for me to go to graduate school, so it’s really nice that now I’m in a privileged position right now to empower other people. We are able to inspire the next generation.”