Analog is the New Digital

As virtual worlds grow more sophisticated and lifelike with each passing day, it is easy to forget that material reality is still where we live our physical lives, and that virtual digits must in most cases be transformed into physical things before they have any meaning or value. Nicholas Negroponte, in a famous statement at the beginning of the Internet Age, declared that “the future is about bits, not atoms.” But people are made of atoms, and atoms still constitute the stuff that remains our greatest desire.

In the Beginning

For thousands of years people have expressed themselves through the creative arts, finding ways to channel their ideas into material form by the skillful exercise of craft. The simplest technologies, such as pencil and paper or paint and canvas, have been available to anyone who might wish to use them. But technology-intensive media such as print, film, radio, and television were never accessible to any but tiny elites. So their use was restricted to one-way broadcast of tightly controlled messages from the few to the many. This was true for hundreds of years, from the time of Gutenberg to just a few short years ago.

Then the revolution came

The combination of digital media creation tools and the Internet has removed the financial barriers and enabled anyone with a computer to become a publisher. The age of ubiquitous publishing is upon us. The first wave of creative energy has been channeled into new online media such as blogs, podcasts, and video. Web-based publishing platforms such as Blogger and YouTube make it easy to instantaneously publish text, graphics, and video content and make it available globally.

But while these new electronic media have become simple to use, the oldest medium—print—has remained beyond the reach of most people. Print is complex and expensive, and unlike electronic media it must be physically produced and distributed before it can effectively communicate anything. So while electronic publishing formats have been embraced by millions of new users around the world, print remains largely the domain of traditional capital-intensive businesses.

But what if print were as easy to use as Internet blogging and video publishing? What new forms of ubiquitous print publishing would emerge? These questions have been inspiring research and experimentation in RIT’s College of Imaging Arts and Sciences for the past five years. The Printing Industry Center, an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Industry Studies Center, has focused on the emergence of radically new print communication models based on digital print and the Internet. These new models are at the core of a new industry described in the 2005 book The New Medium of Print: Material Communication in the Internet Age, written by Frank Cost,the center’s co-director. This book was the first in a new series about the printing industry authored by researchers in the center and published by the RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press. The second book in the series, Data Driven Print: Strategy and Implementation, by Patricia Sorce and Michael Pletka, explores new uses of print as an adjunct to Internet-based marketing. A third book, by professor Twyla Cummings, concentrating on new directions in print distribution will come out this year.

We know the future of print

RIT also has been at the forefront of technical research that is essential to the new models of print communications. One area of particular strength is in ensuring the accuracy of color. In a globalizing economy, half a world can lie between the design and production of printed products. For the colors intended by designers in one part of the world to be accurately rendered on products manufactured in another requires the highest level of process control and rigorous digital workflows that communicate the subtlest nuances of color design intents. RIT’s Printing Applications Laboratory, drawing on expertise from the university’s School of Print Media, works with major suppliers of digital technology and advanced materials like Kodak, HP, Xerox, Adobe, ExxonMobil, Sun Chemical, and most of the major paper manufacturers to develop methodologies and workflows that guarantee the required color accuracy.

Once produced, some printed products will be consumed and recycled within days or hours, whereas others will be expected to endure for decades and even centuries. The durability and permanence of printed products is a major focus of study for RIT’s Image Permanence Institute. The durability of printed images is important because many of them pass through the postal system where they must endure the physical stresses of handling while retaining the messages they carry until they arrive safely at their destination. Often the need for greatest durability is for messages that will live only for a few minutes or hours once they arrive in the mailbox. At the other end of the spectrum, some printed products will become keepsakes and family heirlooms and must be stable and permanent. For example, family photo albums are expected to endure for generations. So digital processes used for these applications must produce printed products that possess the necessary archival qualities. The Image Permanence Institute uses a number of accelerated aging techniques to determine the life expectancy of printed products. Although most of the print media-related research at RIT is relevant to established applications such as publishing, marketing communications, and packaging, it is the new applications serving entirely new markets that are most exciting. This is where inventors and entrepreneurs are building new technologies and systems to create altogether new business opportunities. One area of particular interest to faculty and students in the visual arts is the digital book. Among the partner companies of the Printing Industry Center are several that make technology that is revolutionizing the way books are produced. These include manufacturers of digital print production technology, digital substrates, and product design software.

In addition to these companies, RIT has established relationships with leading innovators in digital book production. One of the world’s leading companies in this space is ColorCentric, a Rochester-based company that produces books on demand for Internet customers. ColorCentric currently produces and ships more than half a million books each month in order quantities of less than two books on average. The quality of the books produced using digital print production machines, made by Xerox, HP, and Kodak, is indistinguishable from that of traditionally produced books. But ColorCentric can manufacture and ship a single book from an online order in a matter of hours. This enables ColorCentric’s customers to completely eliminate the traditional upfront costs of book publishing. This in turn is launching a revolution in book publishing by removing barriers and allowing millions of new publishers to enter the game.

You are the future of print

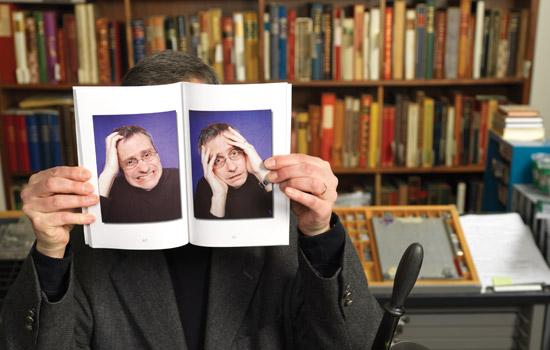

One result of this revolution is having a profound impact on the way RIT professors and students in the visual arts express themselves through media. It is now possible, for example, for professors of photography, graphic design, print media, and illustration to require their students to publish finished books of their work on a regular basis. Frank Cost started what he calls his “Instant Book” project

in January 2006 to inspire faculty and students to think of the book in radically new ways. Each of the dozens of books in the series contains content produced and published in only a few hours. In some cases the content of a book is captured in a matter of minutes or even seconds, thus demonstrating an extreme new frontier for a medium that has always demanded much longer periods of time for its products to come into existence.

With these examples as inspiration, faculty and students are pioneering many innovative uses for books across the university. Student work that would otherwise languish in isolated portfolios is coming together into impressive collections that are much more valuable, in some cases, than the sums of their parts. As this trend grows, new ways to streamline workflows to make it even easier to publish books are being discovered. The greatest barriers are now in the creative process itself, where knowledge of design software is often required. This has led to the creation of a new virtual laboratory in the School of Print Media called the Open Publishing Lab. OPL is a collaborative effort between the School of Print Media and RIT’s Wallace Library, with startup funding from the Printing Industry Center and a small grant from Hewlett Packard to support RIT’s participation in a global research initiative called the HP Digital Publishing University Community. OPL is dedicated to enabling the wider world to use digital publishing to create new opportunities for creative expression.

One of the first groups of OPL projects is the creation of toolsets for people who wish to publish content in book form with minimal experience or time to devote to the endeavor. One tool under development allows for the publishing of automatically formatted and elegantly designed printed books from selected Wiki content. Another project employs a team of software engineering seniors, under the guidance of Fernando Naveda in RIT’s department of software engineering and Frank Cost, and is building a Web-based service for K-12 classroom teachers to quickly and easily publish collaborative books with their students. This project draws upon faculty and student expertise in two RIT colleges, HP, ColorCentric, and the East Irondequoit School District in suburban Rochester.

Analog is the New Digital

The printing world, and the computing devices that drive it, are evolving at an incredible pace. RIT’s vision for the future

of print media in the Internet Age is that it must become a channel of communication as accessible and easy to use as the Internet itself. It must be instantaneous, it must be accessed from any wireless device at any required speed, and it must print images, text, and mixed media from all sources including the Web. Making atoms work as efficiently and instantaneously as bits will be the greatest challenge facing RIT and the print industry in the decades to come.