French Deaf Poets: Renaissance Period

Deaf French Poets Flower During the Renaissance

By: Joan Marie Naturale

|

Two of the greatest French Renaissance poets credited with founding a revolutionary movement in French literature were deaf poets: Pierre de Ronsard, the Prince of Poets, and Joachim Du Bellay. |

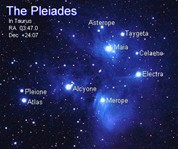

They were members (along with five other aspiring poets and writers) of the “seven stars of French poetry”, the Pleiades, whose mission was to infuse new life into French literature by following Greek and Roman literary models. The Pleiades is a cluster of stars named after the goddesses of ancient Greece and it represented the dream they had of creating French literature that would live on through the centuries.

In 1548, Thomas Sebillet published a pamphlet entitled “Art Poetique Francoys” calling for poets to follow in the tradition of Latin poetry as he was critical of the neo-classical work the Pleiades group was promoting. The Pleiades group disagreed and asked Joachim du Bellay to respond to this treatise. In 1549, a manifesto, “Defense et Illustration de la Langue Francais,” was published, defending the French language as capable of great literature in prose and poetry. At that time Latin was considered to be the only language capable of great literary expression. (Du Bellay 308).

These two poets, deafened at a young age and overcome by solitude, came from similar noble backgrounds, shared interests, loved Latin and Greek books, cherished the French language, and pursued similar work in the royal/papal courts. It is all the more remarkable that these kindred souls found each other and developed a strong bond throughout their lives. They found solace and comfort in poetry and their poet friends. Of the two poets, Ronsard was the leader of the Pleiades and the “brightest, most intense star” (Lang 304). Ronsard was a lyrical genius and created moving sonnets and odes. He was popular in the royal courts as a court poet and was generously compensated with church properties and homes, as well as other gifts. Joachim Du Bellay was another shining star who inspired the Pleiades by publishing the first collection of sonnets, L’Olive, in 1549. This was a seminal work that introduced the sonnet into the French vernacular (Du Bellay 309). The springs of poetry started gushing forth with new lyrical forms and reformed French literature expression.

Both poets were the youngest sons of their families. Du Bellay was born in 1522 at a chateau on the Loire River in Lire. Ronsard was born in 1524 at a castle (pictured) in a picturesque and romantic region, Vendome, on the banks of the Loire River. Du Bellay’s father was an esquire and came from a family of famed soldiers and clergy. Ronsard’s father, Louys, was a noble Hungarian who loved Renaissance culture and composed poetry in his free time. He served as steward to King Francis I.

When Du Bellay was 10, he was orphaned and raised by his brother, who neglected his need for an education, particularly in literature, which he loved. Du Bellay poignantly noted, “My youth was lost like a flower without a hand to tend it”. (Lang 101). He took long walks through the peaceful, scenic French countryside, where he composed poetic works. When Ronsard was 9, he was enrolled in a college of Navarre in Paris and was so traumatized by the experience that he left after 6 months. He then became a page to Charles, Duke of Orleans, and traveled extensively to foreign lands, where he learned to speak languages fluently.

When he was 12, Du Bellay suffered from fragile health and became bedridden for two years, immersed in readings of the Greek and Latin poets. This illness brought about a gradual hearing loss. When Ronsard was 13, he moved to Scotland after princess Madeleine of France married King James V where he too enjoyed long walks in the peaceful Scottish countryside. After her death, he became a squire in the royal stables in the service of the Duke of Orleans. Ronsard became deafened from a fever at age 15 when he and several other companions were shipwrecked on the rugged coast of Scotland. This was a blessing in disguise as Ronsard could no longer pursue a diplomatic career, but was forced to explore other options. He could focus on the clergy, law, or belles letters. While reconsidering his options, he entered the Royal Riding School, was tutored by Lazare de Baif, and wrote Latin and French poems. When he was 18, he traveled to Lemans, where he took vows to be a priest and returned to the Royal Riding School and continued to focus on his writings.

After discussion with his 2nd cousin, a Cardinal, Du Bellay attended the University of Poitiers to study law and started publishing his poetry and verse. It was there that he met Ronsard, and a deep friendship blossomed. Du Bellay moved to Paris to study at the College of Conqueret with Ronsard and other like-minded poets who formed the Pleiades. After Du Bellay published the first collection of sonnets in 1549, he was in frail health once more and confined to bed again. His hearing loss worsened, and he continued his studies of Latin, Italian, Greek, and poetry. He published the 2nd edition of l’Olive in 1551. During this time, his brother died, leaving behind his 11-year-old son to care for. In 1550, Ronsard published Odes, his first book of poetry, and in 1552, published Loves, which was set to music and song by composers.

When Du Bellay was 31, he traveled to Rome with his uncle, Cardinal Jean Du Bellay, as his secretary, and returned in the spring of 1553. They stopped in Lyons, where Du Bellay was feted by fellow poets, and journeyed through the Alps to Rome, arriving in June. He was in the home of the classical authors he loved so much, but he became disillusioned with the papal courts. Du Bellay also felt unhappy at this time, as he had communication challenges that made his job difficult, and he was homesick for France. He fell in love with an Italian woman, Faustina, who was married to an elderly and jealous man. Tragically, their love affair ended when her husband confined her to a convent. Soon after this, Du Bellay returned home in 1557. He continued to work for the Archdiocese of Paris but experienced problems with his cousin, the vicar of the church, who had little patience or understanding of Du Bellay's communication challenges. Du Bellay continued to publish poetry, this time in Latin, in honor of Faustina. In 1558, he published Les Regrets, a poetic diary of his time in Rome and the solemn sonnets of Les Antiquities de Rome. He also published a “Hymne de la Surdité” in tribute to Ronsard, praising his interior poetic ear. Du Bellay believed their deafness shaped them as great poets of the French language.

At this time, Ronsard was working in royal courts as a clergyman. When Charles IX acceded to the throne, Ronsard became court poet and was named the "Father of Apollo”. He was involved with religious and political controversies and was a defender of the Catholic faith. He served the king and the church and was rewarded with income from church properties. He continued to publish poetry, sonnets, odes, and elegies.

Upon Charles IX’s death, he retired to his tranquil chateau at Croix Val and produced some of his best work. He took delight in his gardening work and particularly enjoyed the blossoming roses, his favorite flower. Ronsard (right) and Du Bellay (below) have roses named in their honor, and they are among the most beautiful blossoms.

In 1560, while Du Bellay was composing poetry, he died, and in his word,s "The spirit reunites with the eternal." (Stillwell 150) He was among the great French poets of the Renaissance and was buried with all due honors of a canon. “After his death, Ronsard walked along the Seine, “I wept Du Bellay who was of my age, my craft, my temper, my kin, who died, poor and wretched, after singing so often and so learnedly the praise of princes and kings.” (Lang 101)

In 1585, while on his deathbed, Ronsard composed two final sonnets, one a trumpet call to his soul, the second a farewell to life, and succumbed on December 27th (Stillwell 624). Two months after his death, poets celebrated his literary achievements. Pierre de Nolhac eloquently stated that “Ronsard renewed from top to bottom the matter and form, the inspiration and the vocabulary of our poetry.” (Ingold, 445)

As the brightest and most brilliant stars of the Pleiades, these two poets' works and dreams live on through the eons of time.

References

“Du Bellay, Joachim.” Gallaudet Encyclopedia of Deaf People and Deafness. Ed. John V. Van Cleve. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw, 1987. 308-10. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 21 May 2012.

Ingold, Catherine. “Ronsard, Pierre de.” Gallaudet Encyclopedia of Deaf People and Deafness. Ed. John V Van Cleve. Vol. 2. New York: McGraw, 1987. 443-45. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 21 May 2012.

Lang, Harry G, and Bonnie Meath-Lang. “Joachim Du Bellay.” Deaf Persons in the Arts and Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport: Greenwood, 1995. 98-101. Print.

Lang, Harry G., and Bonnie Meath-Lang. “Pierre de Ronsard.” Deaf Persons in the Arts and Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport: Greenwood, 1995. 304-06. Print.

Mather, Susan M., and Cathryn Carroll. “Hymn to Deafness: Joachim Du Bellay.” Movers & Shakers: Deaf People Who Changed the World. San Diego: DawnSignPress, 1997. 31-4. Print.

“Noble Poet: Pierre de Ronsard.” Movers & Shakers: Deaf People Who Changed the World. San Diego: DawnSignPress, 1997. 101-05. Print.

Stillwell, Adelaide B. “The Poet Among Princes: A Study of Ronsard.” Volta Review: 622-24. Print.

Stilwell, Adelaide B. “Joachim Du Bellay.” Volta Review (Feb. 1914): 148-152. Print.

Blog Information

Blog Archive

- February 2026 (3)

- January 2026 (3)

- November 2025 (1)

- September 2025 (1)

- August 2025 (2)

- May 2025 (6)

- February 2025 (1)

- December 2024 (10)

- October 2024 (9)

- September 2024 (8)

- July 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (4)

- April 2024 (5)

- March 2024 (4)

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (6)

- October 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (5)

- August 2023 (1)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (2)

- April 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (4)

- February 2023 (4)

- September 2022 (5)

- June 2022 (2)

- May 2022 (3)

- April 2022 (7)

- March 2022 (11)

- February 2022 (1)

- October 2021 (24)

Add new comment