Hot Wheelz Racing builds new vehicle for national solar car challenge this summer

Team brings together resources from alumni to international collegiate peers to build solar car

Scott Hamilton

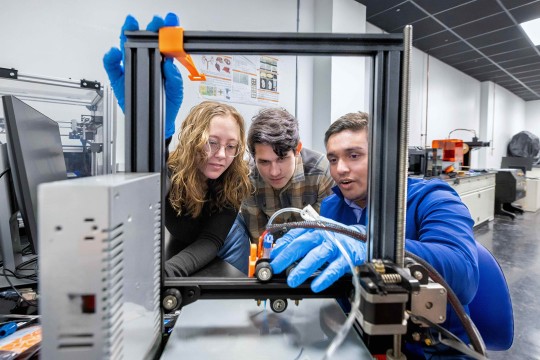

A few members of the Hot Wheelz team took a break from building their solar racecar: front row, left to right, Shannon Nosal, project manager; Sarah Rosen, Wheelz lead; Amarisse Rodriguez, driver interface lead; Sarah Babcock, team manager; Mari Carmen Fuentes, driver interface lead; Aurora Meinsen, Wheelz lead. Back row, left to right, Alexis Smith, propulsion and controls; Katherine Jancevski, finance lead; Apsara Som, chassis lead; Sarah DaSilva, associate designer; Jonina Yang, electrical manufacturing lead.

Hot Wheelz Racing is going solar.

Shifting gears from a Formula-style racecar to building a 16-foot solar vehicle, the team is preparing for its first Sun Grand Prix, taking place this summer in Kansas.

Moving to a new technology is not a surprise to those familiar with the team. Their original race car began 10 years ago as a go-kart and, since then, has developed into an award-winning Formula hybrid vehicle. Gone are the internal combustion engine and hybrid electrical components, which will be replaced with solar arrays, high tech sensors, and lithium-ion batteries.

“We knew we were going to learn a lot with this project. We’re getting this done through peer dedication and a lot of people putting in a lot of hours,” said Shannon Nosal, Hot Wheelz team project manager. The fifth-year mechanical engineering major from Old Lyme, Conn., leads a team of 30-plus undergraduates on several sub groups developing propulsion and controls, building driver steering equipment and learning how to machine different system parts.

“If you manufacture it yourself, you know how to design,” said Willow Shendge, a fifth-year mechanical engineering student from Reading, Pa., and project mechanical lead. “You learn by doing, and you are better at working with others in the workplace on design teams.”

That collaborative focus and long-range planning is key. Over the past three years, the team sought out alumni across the country and collegiate partners around the globe to be involved in the development process. They also engaged faculty and staff with expertise in solar design and alternative materials to help provide new skills for team members.

Originally an all-female team, Hot Wheelz, now open to all students, is dedicated to professionalism, mentorship, experiential learning, and in preparing women for leadership roles through real-world design and build experience. In recent years, the team has increased contributions from peers across campus to support technical, communications, business, and industrial design needs for the team.

One of the biggest investments is in the solar cells needed. Hot Wheelz won its 850-watt array through a drawing at a conference the team attended in 2021. Donated by Sun Power, a residential and commercial solar technology company, the cells are incentives for new, deserving teams.

The team connected early-on with Santosh Kurinec, professor of microelectronic engineering in RIT’s Kate Gleason College of Engineering, and a solar technology expert, for advice about sourcing, testing and installation of the solar cells.

Experienced teams recommended not designing the vehicle chassis from scratch. For a first-year team, the process could take up to three years. Hot Wheelz purchased design specs from an Australian university and modified them to comply with U.S.-based competitions. They will manufacture a flat-top car made of composite materials fabricated in the machine shop located in the Kate Gleason College of Engineering. More than three tons of industrial strength foam was shipped to RIT to prepare the mold for a 16-foot, four-wheeled vehicle with a driver dome and interior, wireless control panels.

Hot Wheelz expects to compete in the 2023 Formula Sun Grand Prix, a track event with national and international collegiate teams. It is also a proving ground for the more demanding American Solar Challenge, a cross-country journey. Hot Wheelz has set its sights for this race in 2024 but must place well in the Sun Grand Prix, a closed track competition where teams measure laps and maneuverability over several days. Cars can reach between 45 and 75 miles per hour, depending on event rules and safety. Solar arrays can use hundreds to thousands of cells that convert sunlight into electricity to power the vehicle. Solar team budgets can range from $25,000 (for retrofitting older model cars) to millions for vehicles made of state-of-the-art composites and systems.

Early solar cars sped along tracks and highways in the 1990s. RIT’s first entry came in 1993 with a team participating in the GM Sunrace USA. The next time RIT would have a solar car connection was in 2012 when the university was the launch point for the American Solar Challenge. They did not have a car entered at that time.

After several months planning and working with other teams, even driving competitors’ cars, RIT will join a tight-knit, collegiate solar car community.

“They have been so good to work with and helping us move along toward the competition,” said Kathleen Lamkin-Kennard, professor of mechanical engineering and team adviser.

Hot Wheelz is also joining a community focused on building vehicles and understanding how technology translates into a car that can be used in the future.

“The competition seems to be moving in that direction, toward more practical applications,” she said, noting that the students are learning to apply class work and new skills through performance teams such as Hot Wheelz. “Projects such as this help them gain technical expertise and confidence. They are able to see successes and failures and learn from them. This work is so much a part of them.”