Psychology professor creates big team science network for otter research

ManyOtters brings together institutions from across the nation to expand and enhance data sets for otter cognition research

Carlos Ortiz/RIT

For the first round of ManyOtters experiments, the otters were given nine different foraging puzzles to solve. They worked with these puzzles in two different instances to assess their long-term retention.

Researchers who study animals face a common problem. When working with one institution, the pool of study participants is limited. A small sample size can lead to less precise conclusions and presents barriers for those interested in comparative analysis across species.

That’s why Caroline DeLong, a professor and undergraduate program director in RIT’s Department of Psychology, established the ManyOtters project in partnership with Heather Manitzas Hill, professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at St. Mary’s University, and Deirdre Yeater, professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at Sacred Heart University.

The project brings together dozens of institutions from across the nation to explore the same research questions and offer the same puzzles to test the cognitive abilities of otters.

Carlos Ortiz/RIT

Caroline DeLong, left, and student Rose Khoobyar, right, record and discuss their observations as Gary the otter completes a foraging puzzle.

“Although it’s been wonderful collaborating with Seneca Park Zoo, I came to a point where I was frustrated with only having a few otter subjects to complete my studies. As a scientist, you want to base your conclusions on as many subjects as possible,” said DeLong, who has conducted research with otters and other animals at the zoo since 2010. “When I saw people banding together in these big team science groups to explore one research project across a large number of individual subjects, I decided to start ManyOtters.”

The goal of ManyOtters is to “address important outstanding questions that individual labs could not answer by themselves,” with a direct focus on otter cognition research. The first round of experiments are foraging-based puzzles that test long-term retention, where the otters are offered nine foraging devices at two time points to assess their ability to solve, and remember the solutions, to each puzzle.

“We all only have so much bandwidth, and sometimes we need input from others to help see data or problems from different perspectives,” said Manitzas Hill. “I also love sharing responsibility with a collaborator. We get to motivate each other, share the burdens that come with conducting research, and get excited about progress together.”

Yeater added “Our collaboration on the leadership team has also been deeply rewarding in allowing us to champion other women in science while fostering an environment of shared learning and mutual support. We work effectively as a team, continuously improving the quality of our research through innovative ideas and complementary skills.”

A high school science fair sparked DeLong’s love for animal cognition and the scientific process. Sharing her passion and igniting that spark of curiosity within student researchers in her Comparative Cognition and Perception Lab is one of many perks of her work.

DeLong, director and principal investigator for the lab, explained that she wouldn’t have the time to complete this work without the help of students.

“I think that participating in something like this helps students prepare for the next step in their careers. It’s beneficial for them to see that we’re part of a giant collaboration, which is very different from what most students are exposed to,” she said. “It adds another tool to their skill set for thinking about data analysis and how to set up projects.”

Carlos Ortiz/RIT

After a day of collecting data, students Maya Garaway, left, and Rose Khoobyar watch the otters play in their enclosure alongside Caroline DeLong.

This rang true for Anna Sofia Hege ’25 MS (experimental psychology). Hege, from Syracuse N.Y., worked with DeLong in the CCP Lab for two years. Now that she’s graduated, Hege is continuing to study animals as a research coordinator of the Language Research Center, a primate lab at Georgia State University.

She said her time with the lab and her work on the ManyOtters project introduced her to new connections and ideas that she wouldn’t have found otherwise.

“Learning about the importance of communication and organization to help coordinate such a massive project is really helpful for the position I’m in now. Communication is key when you’re working with a bunch of different moving parts,” she said.

For Rose Khoobyar, from Avon, N.Y., the opportunity to engage in this far-reaching, hands-on research was enticing.

Khoobyar is a third-year RIT Honors Program student pursuing degrees in psychology and experimental psychology through the combined accelerated bachelor’s/master’s degree program. She was introduced to DeLong’s lab during her first-year student orientation. While she originally planned to pursue psychology as a pre-law degree, seeing DeLong’s work inspired her to pivot and pursue a research-based career.

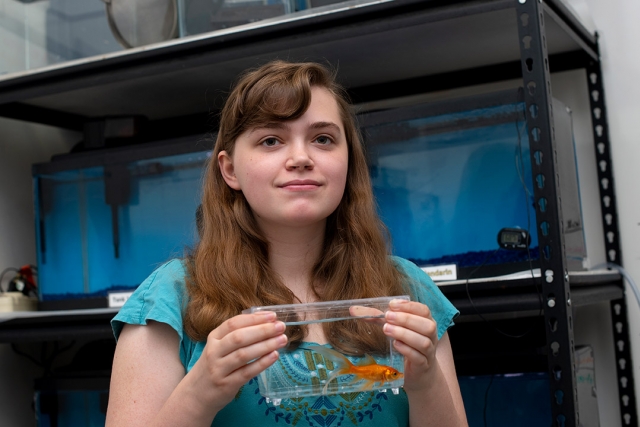

She worked as a lab manager for DeLong over the summer and continued to be an important part of the lab through the fall semester, assisting with everything from cleaning fish tanks to conducting and recording experiments with goldfish, baboons, and otters. Being able to participate in a big team science project was an unexpected perk.

“This kind of collaboration not only replicates some of the work that I will actually be doing beyond graduation, it’s also a really good opportunity for networking,” she said. “Getting to hear about other people’s research journeys and learning about what other people are doing in the field is a very good experience.”

The ManyOtters team is open to new collaborators. The team encourages zoos or aquariums that house any species of otters, or any scientists that conduct otter research, to visit the ManyOtters website for more information and to learn how to get involved.