RIT researcher looks for genetic switch to prevent ‘sleeping sickness’ in cattle

U.S.D.A. National Institute of Food and Agriculture funds study

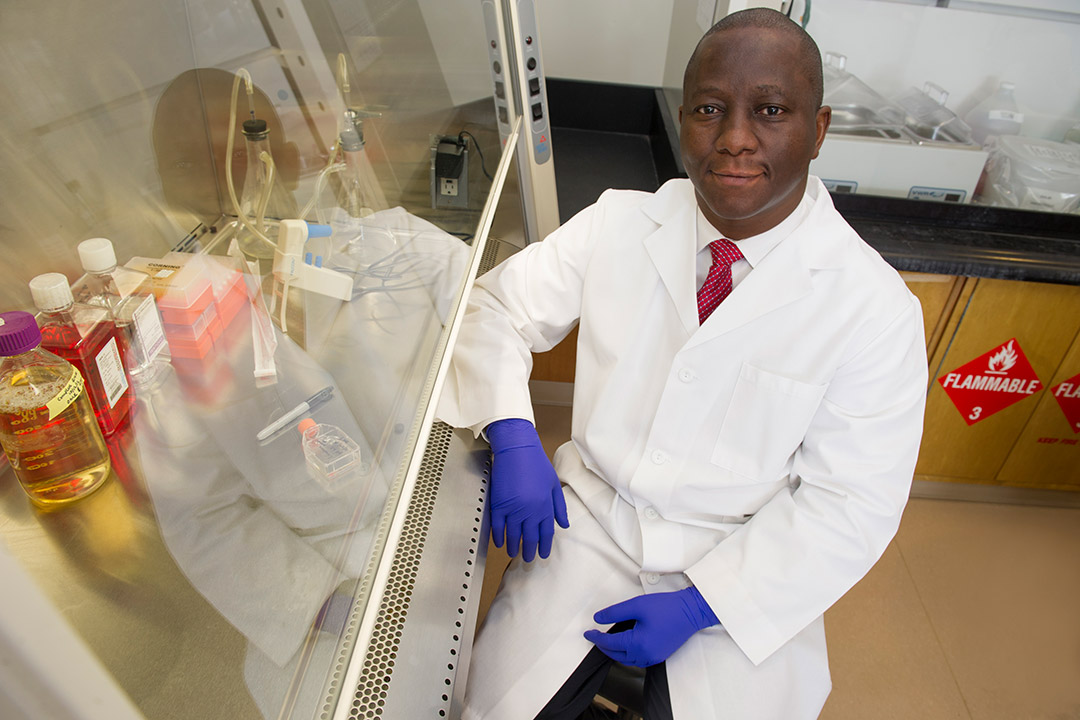

Elizabeth Lamark

RIT professor Bolaji Thomas’ genetic research on an infectious bovine disease could protect cattle on different continents.

As parasites adapt to a warming world, an infectious disease expert at Rochester Institute of Technology has his eye on the tsetse fly in sub-Saharan Africa. The biting fly transmits Trypanosomiasis, or “sleeping sickness,” to cattle there and could someday migrate to northern climates, including to the United States.

RIT researcher Bolaji Thomas is leading a $650,000 study funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative. The aim of the research project is to compare the genetic response in cattle to the parasitic disease that attacks their blood and brain. Outbreaks decimate cattle herds in Nigeria and neighboring countries, resulting in food insecurity and economic hardship.

Global climate change makes the problem in sub-Saharan Africa a potential threat elsewhere because the tsetse fly and Trypanosome parasite can migrate and adapt to genetically similar flies and cattle breeds in other parts of the world, according to Thomas, an RIT professor of biomedical sciences.

“When we speak about adaptation of local vectors or their transport of them from endemic countries, it’s just a plane ride or a ship ride away,” Thomas said. “If we aren’t careful, the vectors that we thought couldn’t survive here will get introduced here and become a big problem. If we have learned anything from the spread of COVID-19, it is to be prepared. That’s why this project has major significance.”

Federal funding supporting the study underlies the need to protect the U.S. cattle industry from future scenarios in which Trypanosome arrives and thrives here. The genetic similarities between cattle breeds in the United States and those in the study make the research especially relevant, Thomas said.

The project centers around Thomas’ collaboration with Emmanuel Obishakin, a veterinary parasitologist at the flagship veterinary center in Nigeria—the National Veterinary Research Institute, which is home to the National Center for Trypanosomiasis Research—and Olanrewaju “Lanre” Morenikeji, assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford.

Thomas’ team will conduct the RNA transcript sequencing and profiling at RIT using purified RNA from infected cattle at the National Veterinary Research Institute in Nigeria.

The researchers will characterize and analyze immune gene expression to identify genetic markers associated with disease tolerance and susceptibility among different cattle species. Their work will map genes of interest to exploit the evolutionary adaptation that allows one cattle species (N’Dama) to survive the same disease that kills another one (White Fulani).

Prior research by Thomas and then-postdoctoral researcher Morenikeji showed that a specific gene (CD14) in both breeds evolved differently in response to the Trypanosome pathogen and that natural variants of this gene protect the N’Dama breed.

Thomas builds upon their findings in the current project by combining analytical tools and using messenger RNA and non-coding RNA to make separate genetic profiles on a cellular level for each of the animals in their study.

“We are asking if we can find biomarkers that could be used to breed new species of animals to tolerate disease or design new drugs to protect the animals,” Thomas said. “That’s the main goal.”