Historic theater pipe organ destined for RIT

Carlos Ortiz/RIT

Organ technician David Bottom, left, and restorer Carlton Smith install galvanized steel piping that will take air from the pipe organ’s blower to its chambers in RIT’s music performance theater, which is under construction. The historic pipe organ, which has thousands of parts and is nearly 100 years old, has been under restoration by Smith since 2020.

The first pieces of a massive, historic theater pipe organ built more than 90 years ago have been installed at Rochester Institute of Technology’s music performance theater, currently under construction.

About 240 feet of galvanized steel piping that will take air from the organ’s blower to its chambers was installed in December by Carlton Smith, a professional theater pipe organ restorer who has been helping bring the historic instrument back to life in his Indiana workshop since March 2020. Several more trips to Rochester will be needed to complete the installation prior to the theater’s grand opening in 2026.

The organ is unique, so the theater’s pipe chambers were designed specifically for it, mimicking the chambers from its original home, the Hollywood Theatre in Detroit.

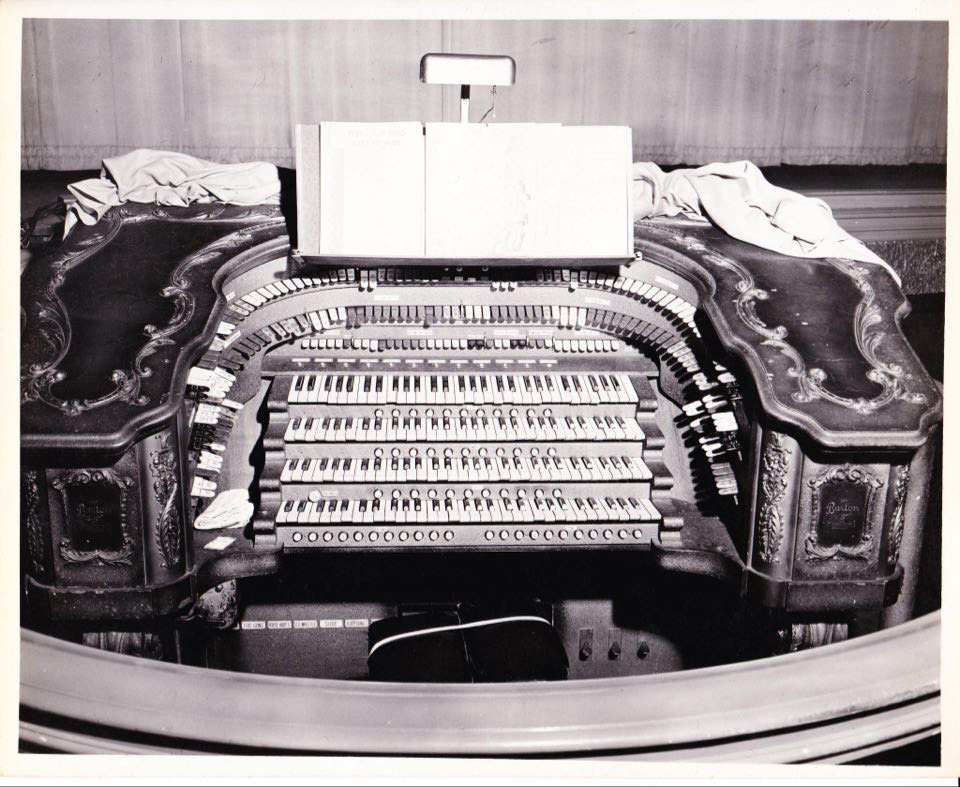

Components of the organ, a Barton Opus 234, are two-stories tall and can fill a tractor trailer. It has thousands of parts, including pipes, wind-chests, keyboards, and pneumatic mechanisms of metal, wood, and leather, producing a diverse array of sounds that can simulate an orchestra in surround sound.

The organ was built in 1927 and had a list price of $75,000. It features hundreds of pipes— ranging from inches to many feet tall—and four keyboards that could play notes sounding like dozens of instruments, from sleigh bells to a marimba harp, xylophones, trumpets, and drums.

News about the restoration and the organ’s future destination was featured by the Associated Press last summer, and the story made headlines around the world.

“This magnificent instrument will not only serve as a centerpiece for our new music performance theater, it will also help our students appreciate the relationship between music and mechanics. They will literally be able to walk through a working instrument and see how sounds are produced,” said RIT President David Munson.

With more than 2,000 students in the past five years receiving performing arts scholarships, RIT continues to lure more students involved in performing arts—something that may sound strange for a college with "technology" in its name and no performing arts majors. But Munson points out that abilities in music and math are highly correlated, so most of these students are majoring in STEM disciplines, bringing creativity, out-of-the-box thinking, and collaborative skills to campus.

The organ was one of more than 7,000 installed in American and Canadian theaters between 1908 and 1929, and more than 130 were in Detroit alone. The organs provided music during showings of silent films and vaudeville acts.

Roger Mumbrue

The console of the Barton Opus 234 pipe organ when it played at the Hollywood Theatre in Detroit, from 1927 to 1956. The massive instrument, which has thousands of pieces that are two-stories tall when assembled, will be the centerpiece of RIT’s new music performance theater, set to open in 2026.

Luminaries such as Bob Hope, Jack Benny, and Sophie Tucker performed in the 3,436-seat Hollywood Theatre, which was described as opulent and gargantuan, with velvet curtains, mirrored niches and ceilings covered with large medallions drizzled with gold and shimmering silver. A news report at the time said it was “one of the most beautiful, most comfortable theaters in the universe.”

But with the advent of television, most grand movie houses eventually closed, as did the Hollywood Theatre in 1956. Few organs survived intact, but this one was purchased at auction for $3,150 by Henry Przybylski, an engineer and organ buff from Dearborn Heights, Mich. It took five months to remove the components of the organ before the building was demolished in 1963. The organ remained stored in thousands of pieces for the next 40 years—longer than it had been in the theater—in Przybylski’s garage, attic, and basement.

After Przybylski died, his widow agreed to sell professional organist Steven Ball the entire instrument.

“Getting it playing again would be such a massive undertaking, and she was quite concerned others would take it for parts, or scrap,” Ball said. “Here I was, a young 20-year-old who was part of the organ culture in Detroit, but I wanted to make sure it someday returned to a home as it was. I liquidated my life savings and sold my car. I used everything I could to secure the organ and buy enough lumber for packing. Imagine an 18-wheeler semi fully packed from floor to ceiling. That’s how much space this undertaking took.”

Ball taught organ and carillon at the University of Michigan, where Munson was dean of the College of Engineering prior to becoming RIT president. While at UM, Ball proposed and led the development of a cross-disciplinary course in music, engineering, and art, focused on the design and production of a small carillon.

“The purpose was to teach freshmen about bells and bell tuning, to make bells at their bronze foundry at the school and explain what a carillon bell is,” Ball said. “So, in 16 weeks, students go from beginning freshmen to engaging in a musical performance.”

Ball said he received an email from Munson in 2019 asking about significant theater organs that might be available, knowing that Ball, earlier, had one in storage with no prospects for a final home for long-term preservation.

Ball still had the Barton, so he came to RIT to meet with Munson about the prospect and made arrangements to donate it to RIT.

“My goal was to house this in a public place where it would be exactly what it was and give it back to the world because what it had to offer was so culturally different,” said Ball. “I felt so strongly about preserving the organ as an American art form. This instrument is so different than anything these students would normally be exposed to. It’s so radical and extreme. It’s not your typical church organ.”

Munson would like Ball to play it on opening night when the theater opens.

“I couldn’t possibly be happier that the organ found a good fit,” Ball said. “It’s not just going to a public venue. This is going to an environment where you have some of the brightest minds who hold the future of the world in their hands. This will help to specifically engage those minds, and they will see that the inside technology is a compilation of physics, arts, and engineering. The interaction is what makes this exceptionally cool. This instrument has the potential to inspire these students who are going to change the future.”