RIT ‘star hunters’ use AI to uncover rare clues about the life and death of celestial bodies

NTID astrophysicist Jason Nordhaus and Ph.D. student Bailey Filer are part of a collegiate collaboration

Matthew Sluka/RIT

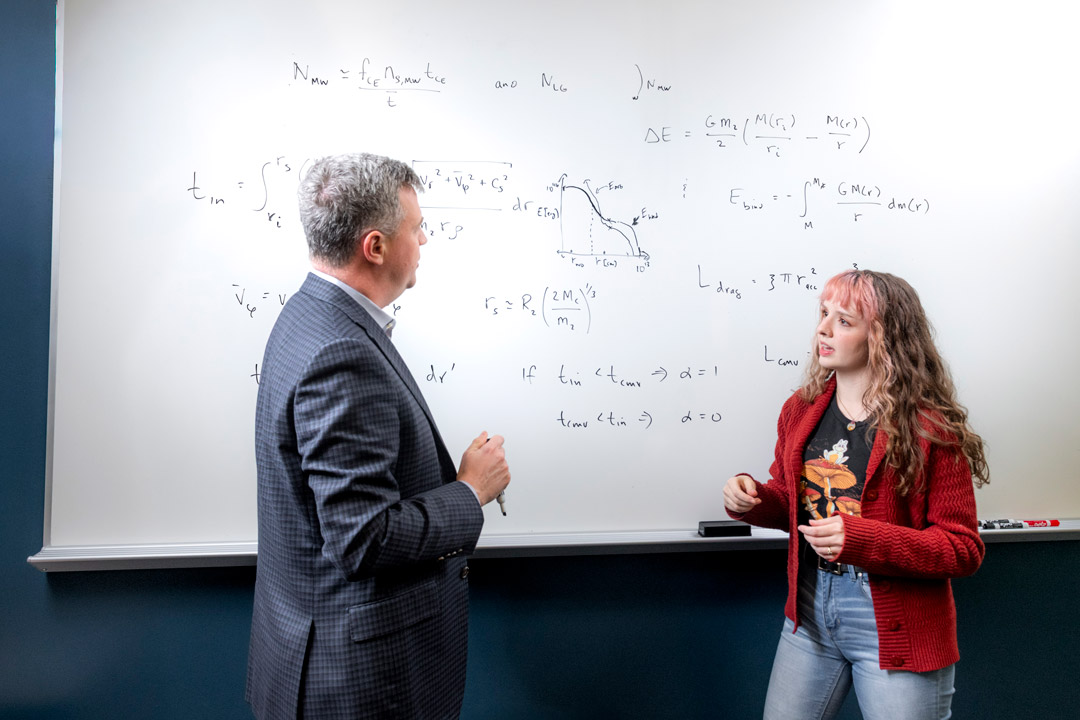

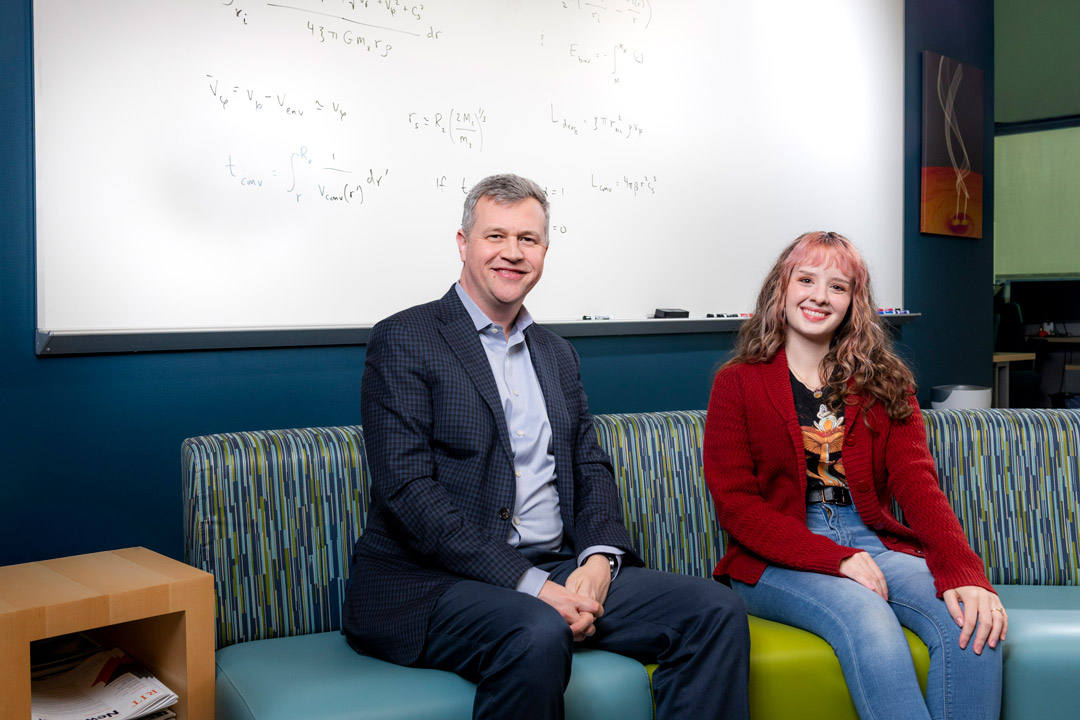

Associate Professor Jason Nordhaus, left, and astrophysical sciences and technology Ph.D. student Bailey Filer have developed a mathematical method that searches astronomical data for signs of hidden star systems.

Every year, somewhere in our galaxy, a brief event happens—one star consumes another, revealing important clues about the processes by which stars die. However, since these rare star collisions often go unnoticed, an astrophysicist at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf and his doctoral student are helping to lead the effort to change that.

Jason Nordhaus, associate professor of physics, is using funding from the National Science Foundation to hunt for star systems that could enhance our understanding of how stars die, merge, and create the close binary systems that produce gravitational waves.

Matthew Sluka/RIT

Associate Professor Jason Nordhaus, left, and astrophysical sciences and technology Ph.D. student Bailey Filer

“The systems we are looking for are composed of a star in a one-day orbit around the dead core of the star it tore apart. Identifying these binaries in clusters holds the key to answering one of the biggest unknowns in stellar astrophysics,” explained Nordhaus, who is also a faculty member in RIT’s Center for Computational Relativity and Gravitation. “Star clusters provide extra information that can be leveraged, such as their ages, compositions, and the evolutionary state when the star was consumed.”

The challenge is that the clues he and his research team are looking for are fleeting. The type of star systems that provide this information form only when one star engulfs another, a rare process that might happen just once a year in the Milky Way. If astronomers aren’t looking at exactly the right moment, the evidence disappears.

To solve this problem, Nordhaus is using artificial intelligence and machine learning. His team, which includes RIT astrophysical sciences and technology Ph.D. student Bailey Filer and collaborators from the University of Toronto, Boston University and the University of California San Diego, developed a mathematical method that searches astronomical data for signs of these hidden star systems.

Using this approach, they have identified an unheard of 52 potential star system candidates within our galaxy. Of those, several were hiding in well-studied clusters, and one, according to Nordhaus, is “pristine,” offering an ideal example for studying how stars evolve through what scientists call the “common envelope phase.”

This phase—when two stars share a single, bloated outer layer before eventually separating or merging—is a particularly mysterious process. It is also critical for how binary black holes—the sources of gravitational waves—are formed. Nordhaus’s research has mapped a plan to use the newly identified systems to determine how stars change before and after the common envelope phase.

Filer, who is gaining hands-on experience analyzing stellar data, is focused on the theoretical and simulation side of the project and is excited to be part of research on the cutting edge of binary astrophysics.

“The work that I’m doing takes just a little chip off of the problem we’re studying, and many other people are going to continue to chip away at it,” she said. “That kind of collaboration is really cool in and of itself.”

As for doing his part to develop the skills of a new generation of scientists, Nordhaus always looks to incorporate students into his research projects.

“There can be a perception that students in labs aren’t performing critical tasks but, at RIT, our students, from undergraduates to doctoral candidates, are an integral part of our research. As a team, we look forward to experiencing that never-ending enthusiasm for science and discovery together.”