RIT researchers to create serious video game for infrastructure resilience to cyberattacks

Army Cyber Institute at West Point selects RIT to develop cyber game for training and education

Emily Nack

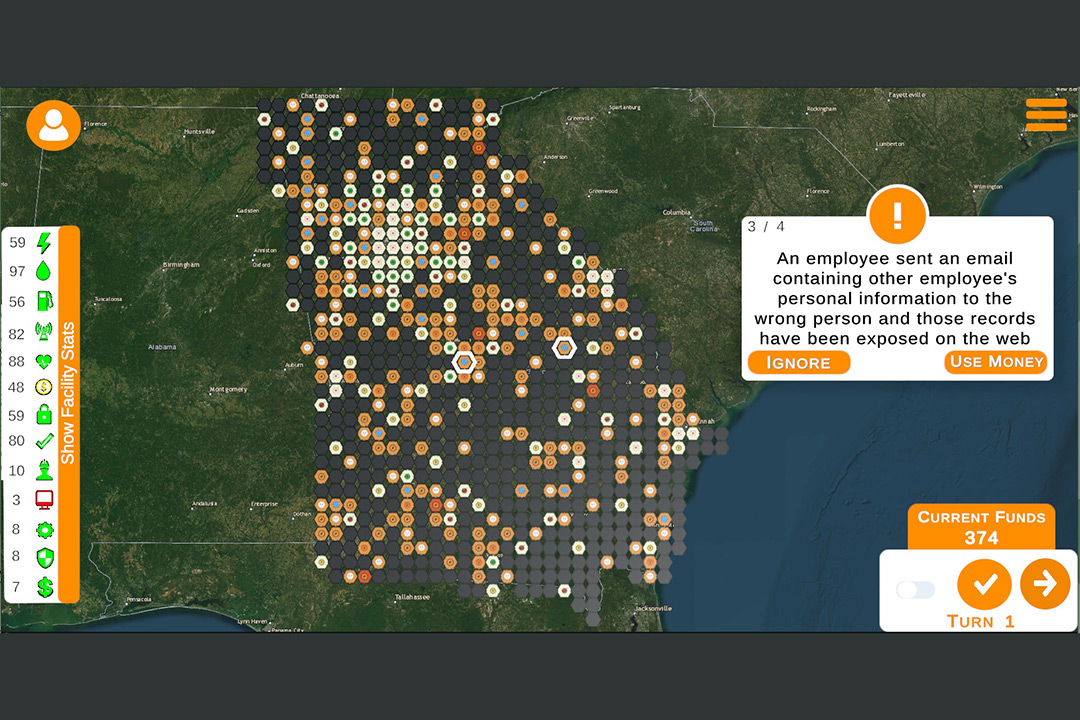

RIT researchers are developing a serious game that allows city leaders to prepare for multi-sector cyberattacks. This screenshot from the game prototype depicts a cyber threat affecting the state of Georgia.

Researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology are building a serious video game to help cities prepare for, prevent, and respond to cyberattacks. RIT received a more than $600,000 grant and was selected by the Army Cyber Institute (ACI) at West Point to develop the cyber exercise game and a framework for future development.

The game will allow city leaders to learn how multi-sector cyberattacks can affect their city’s critical infrastructure—from the electricity grid to first responders. By building a playable video game and integrating real-world geographic information systems (GIS) data, the designers hope the immersive game will boost critical infrastructure resiliency and highlight technical and policy interdependencies.

“From ransomware at hospitals to data leaks, there are so many cyberattacks happening and I’m sick of them,” said David Schwartz, director of RIT’s School of Interactive Games and Media and principal investigator of the project. “Gamified experiences are proven learning tools, and we’re excited to leverage them to help save lives.”

The project is an expansion of a tabletop research experiment named Jack Voltaic, which was created at the Army Cyber Institute in 2016. Players from multiple sectors—including first responders, emergency management, transportation, telecommunications, power, water, finance, military, and healthcare—would collaborate in response to any cyberattacks, building a framework along the way. Throughout several iterations, in-person exercises were done in New York City, Houston, Savannah, and Charleston.

In early 2022, the ACI began working with RIT’s Army Educational Outreach (AEOP) Apprenticeships and Fellowships program to extend Jack Voltaic with GIS and game-engine capabilities as a proof-of-concept. Three co-op students were hired to begin creating a playable prototype.

The multiplayer prototype allowed a blue team of infrastructure leaders to communicate and strengthen their facilities. There was also a red team of malicious actors or cyber adversaries, who aimed to compromise facilities and go unnoticed with their actions. The simulation was created using the Unity game engine. It also integrated GIS data, including maps and population data. As different threats arose, leaders could work together to determine how to resolve the situation.

“This game was so different than any other project I had worked on and I liked how strategic it was,” said Emily Nack, a 2022 game design and development graduate who was project lead of the co-op team. “I could see the real-world, positive impact that this game could make.”

Nack’s co-op experience led to a full-time job. Upon graduation, she was hired as an IT specialist by the ACI at West Point.

“After seeing the game concept, the ACI then decided to expand the project to include an open-source game product,” said Paul Maxwell, deputy director of the ACI at the United States Military Academy West Point. “RIT was selected based upon its gaming expertise.”

Throughout the next two years, RIT experts will work to further develop the video game. The team will add better user interfaces, incorporating more GIS data, and work on data-oriented programming to make sure the game is playable on many different machines.

Co-principal investigators for the project include Brian Tomaszewski, professor of geographic information systems, and Jessica Bayliss, professor of interactive games and media. The team will also work with RIT’s ESL Global Cybersecurity Institute, Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences, Console Development Lab, Center for Geographic Information Science and Technology, and Niantic x RIT Geo Games and Media Research Lab.

The game developers see the game as a social simulation where stakeholders can get together to practice various scenarios, allowing them to learn what works and what doesn’t work. As a video game, the designers also want it to be customizable, so leaders from any city can train.

“A picture—and in this case a video game—says a thousand words,” said Schwartz. “Real people’s lives are at risk here. We want our infrastructure leaders to realize the true impact of their work, and an immersive video game is a great way to do that.”