Graduate student’s research in identifying image manipulation can help lead to media literacy

Student’s work adds to growing capability in media forensics at RIT

Nearly 80 percent of respondents to Emily Shriver’s online survey stated this image was manipulated. Her research study was about media literacy and the need for individuals to be more aware of how images are used in news environments.

Emily Shriver was thrown into the world of media forensics—and enjoyed it.

The print media graduate student headed a project to assess how individuals recognize manipulated images used in news. She found that most people are skeptical about images seen in print or online news, but only half can tell which images actually are altered. In her study, she found that, on average, participants could only correctly identify the image category for 37 percent of the images they responded to in the survey.

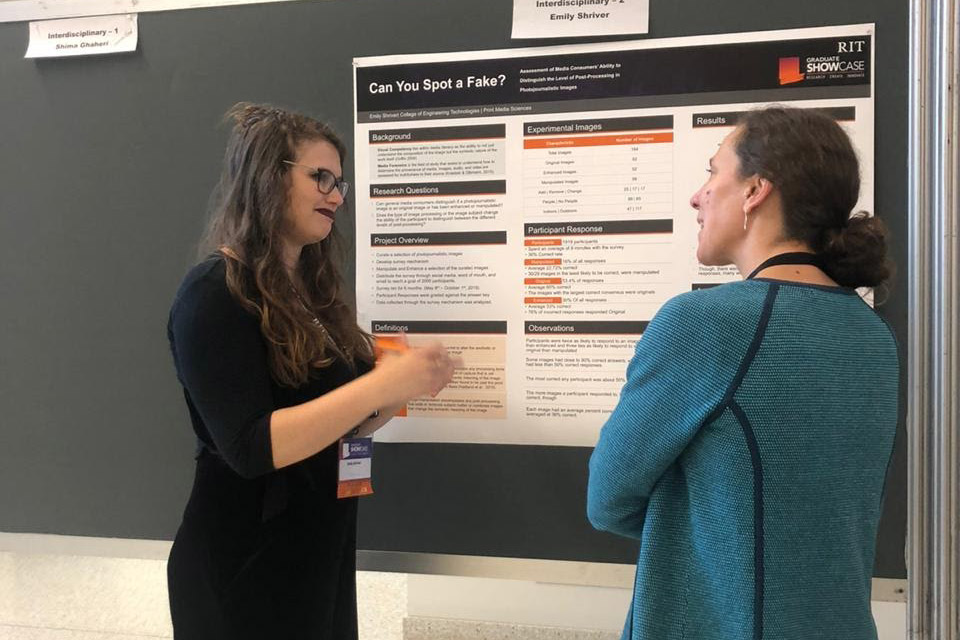

Her work is part of a growing field in which images and news are being challenged as reality, and she believes there are some easy ways people can determine whether images are real. Shriver’s work is being recognized regionally and was awarded top honors at the RIT Graduate Showcase recently.

Emily Shriver, a graduate print media student won best presentation at the RIT Graduate Showcase.

“The more I started taking classes and thinking about this and reading literature, the more I was interested and I found a gap in the research. A lot of it was curiosity,” said Shriver, from Alden, N.Y. “I kept on seeing things that frustrated me in the lack of media literacy among my peers, my family and even in myself some of the time. This work sparked my curiosity.”

Shriver’s online survey used 164 news images from local and regional photographers. Nearly 2,000 individuals participated.

“The hardest part was getting photographers to let me use the images; the photojournalist community is so protective of their images, rightly so,” she said. “The only thing that is keeping our faith in images is the control of them.”

Shriver convinced photographers to give her several “off cuts” – images that were part of their overall series taken at events, but were not selected for publication. She modified some of them slightly and posted the mix of original and enhanced images to the survey site. Participants were asked to select which were altered, and she found that half were able to correctly determine the modified images. They had the option of answering all the image questions or just selecting one or two. The majority of respondents, however, were up to the task of reviewing all her photos.

“No one did better than 50 percent when they answered all the questions about the images,” Shriver explained. “It was pretty linear, with a threshold, where the more images people responded to, the better they did. There was no major drop off. But there was a big gap between the highest performers and the lowest. Why no one failed completely was there was a 3-1 bias in saying that an image was original versus manipulated; and a 2-1 bias saying it was original versus enhanced.”

Shriver’s work has been recognized on the blog site Media Literacy Now and received “Best Presentation” accolades at a recent RIT Graduate Showcase. Her survey was part of her master’s thesis “Assessing average media consumers’ ability to distinguish between types of postprocessing of photojournalistic images.”

During the time she conducted the research she was also involved in the MediFor Project. MediFor—short for media forensics—is the scientific analysis of recorded media in the form of audio, video and still-imagery evidence obtained during the course of investigations and litigious proceedings. RIT’s work, led by Christye Sisson, professor and director of the photographic sciences program in RIT’s School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, is creating high-provenance data and image manipulations as part of the project’s data team, led by PAR Government Systems Corp., a government contractor based in Rome, N.Y. Shriver has worked for the latter company since 2016 as a systems engineer while continuing her graduate studies and involvement in this latest research. The difference between manipulated versus enhanced in reference to photos is significant because of the growing interest in understanding the thinking behind people’s impressions.

Shriver believes there are sound ways to assess images to improve media literacy.

“The best way to know that an image is truthful is the same thing we do for finding fake works of art—do a provenance test. Look where the photo came from, who did this, what other images are from that event? Things like that, because you are able to put it into the context of where it is from, what it is trying to say, who published it and why,” she explained, adding that some people are skilled in enhancing a photo to its pixel level to reveal something pasted in; others cannot and need to have some simple tools—and a healthy skepticism about images. Her study is a way to raise awareness, too.

“Some people think we are all doomed,” she said laughing. “I know some results show we are not good at this, but that is OK. Everyone can learn. There are tried and true ways to find the truth and with a little bit of effort, everyone can be taught – it is not impossible!”