MISHA

In the late 2010s, cultural heritage and imaging researchers at RIT recognized a need.

The goal of libraries, museums, and archives around the world is to safeguard historical documents and artifacts for future generations. But some objects are damaged before coming into an institution’s care, or they can deteriorate with time.

When text fades or illustrations are painted over, a scholar’s understanding of the object’s history is incomplete. There are imaging systems that can uncover those details, but they cost hundreds of thousands of dollars—much more than most institutions can afford.

Enter RIT’s Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) lab, run by experts from two thriving programs at RIT—imaging science and museum studies. Using funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the lab developed a relatively low-cost system that makes cultural heritage imaging methods more accessible.

The team officially launched Multispectral Imaging System for Historic Artifacts (MISHA) in 2024 with the release of the system and its open-source software. Since then, MISHA has visited institutions across the globe, like the United States Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, University of São Paulo, and Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In South America, cultural heritage imaging helps National Library of Colombia employees gain a better understanding of the country’s history. With support from RIT and the Whiting Foundation, the library acquired two MISHAs in 2024.

“We have a lot of books with redacted text, as well as deteriorated books, that we’re now able to read,” said Lucía Alviar Cerón, art conservator and restorer at the library. “We wouldn’t be able to access the advanced systems that are much more expensive and difficult to use. With the help of RIT, MISHA has been very easy to use.”

MISHA has been demonstrated at or loaned to more than 20 institutions in North and South America and Europe. Outside of RIT, 11 institutions have built their own MISHAs.

Juilee Decker, co-director of the CHI lab and museum studies program director, said forming these connections and increasing access to multispectral imaging can have a great impact on the cultural heritage field.

“MISHA is about reducing canonicity, to show that an object doesn’t have to be incredibly prestigious or proven worthy enough to be imaged,” Decker said. “It can be any object at any institution.”

Imaging science leaders

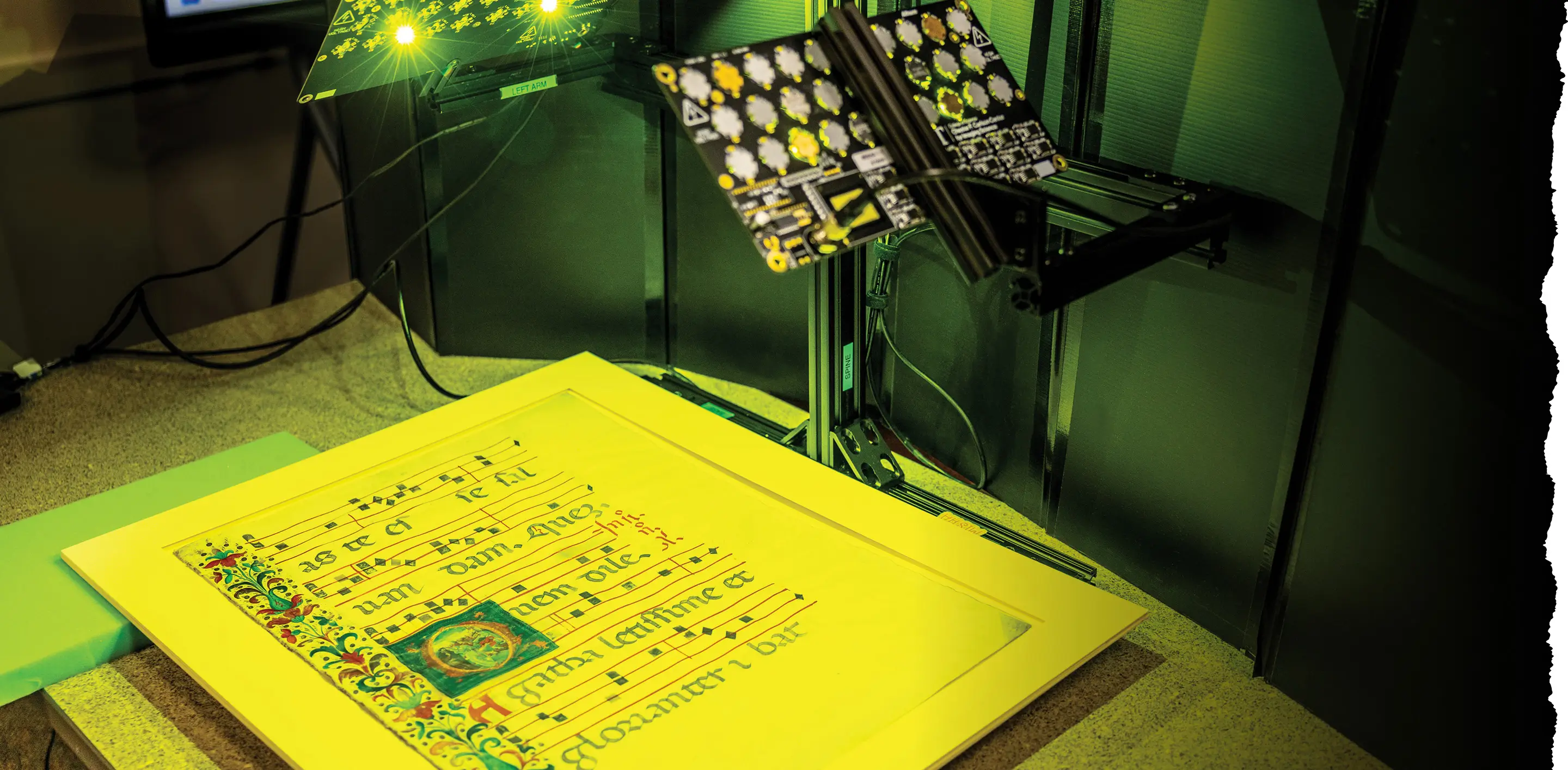

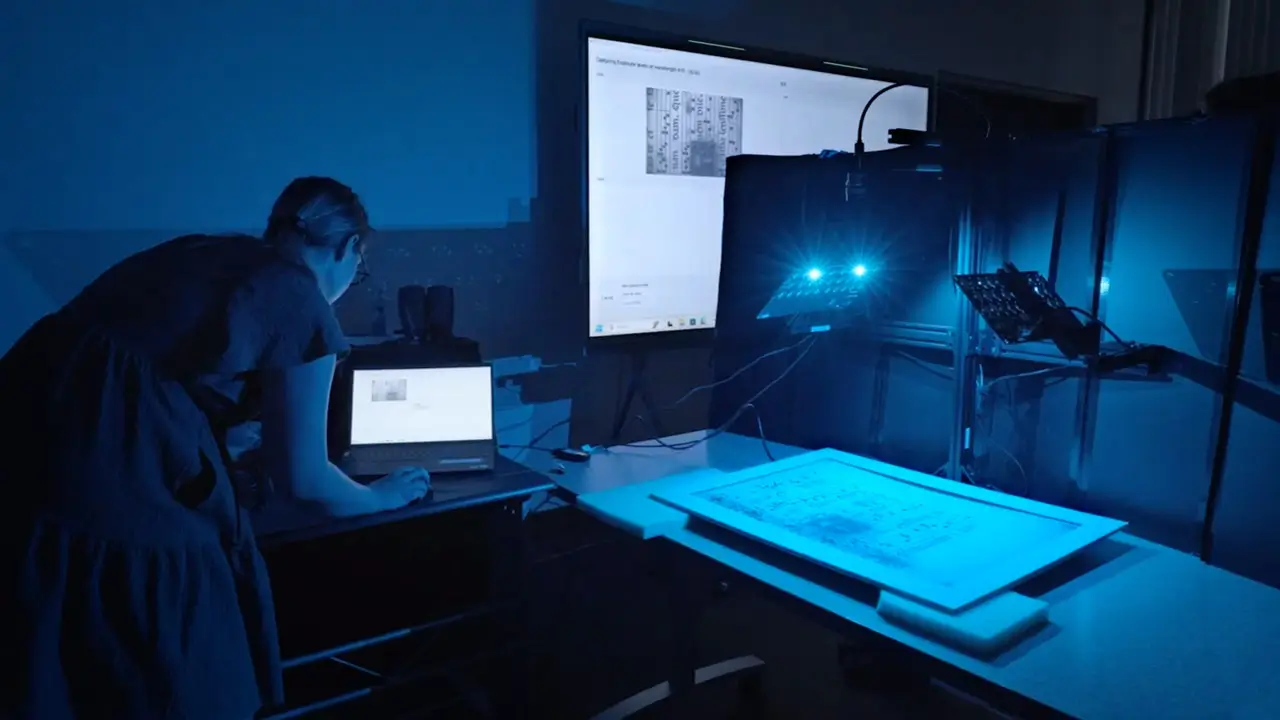

In the darkness of the CHI lab, bright LEDs flash in quick succession as a manuscript is imaged using MISHA. In less than a minute, the system takes 16 photos across 16 different wavelengths of light.

When the collection of images is combined in different ways, it can illuminate features that aren’t visible to the human eye. This technique is called multispectral imaging.

Decker and CHI lab co-directors Roger Easton Jr. and David Messinger collaborated to develop MISHA with support from many students and research specialists. Kevin Sacca ’16 (imaging science) and Tania Kleynhans ’17 MS, ’20 Ph.D. (imaging science) were key contributors during the early phases of MISHA’s development.

Today, anyone interested in building a MISHA can access the blueprints and training materials free of charge. Purchasing the hardware costs less than $10,000, a stark contrast to other systems that carry a six-digit price tag.

Scholars in the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science have made contributions to cultural heritage research for over 25 years. Easton helped image and research several significant documents, including the Dead Sea Scrolls and palimpsests with erased text by Archimedes and from St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai.

“We’ve been able to image a lot of important documents ourselves, but we can’t do it all,” said Easton. “Now, there are scholars across the world who can do this themselves.”

Multispectral imaging is one technique used within the multidisciplinary field of imaging science. Imaging scientists combine physics, math, computer science, and engineering to develop imaging systems for satellites, drones, augmented and virtual reality, and more.

In addition to cultural heritage, multispectral imaging has been used to support the precision agriculture and aerospace industries.

Creating a system that catered to humanities scholars was an inviting challenge for Messinger, professor and Xerox Chair in the Center for Imaging Science. However, overcoming the challenge required working across disciplines.

“When you bring multiple perspectives together, you find solutions to problems that no one individual could find on their own,” he said. “Checking our egos and respecting each other’s expertise allows us to learn from one another as we focus on the bigger picture.”

RIT’s museum studies program takes an interdisciplinary, technology-infused approach to the field that prepares students for careers in museums, libraries, archives, and other cultural organizations. One of the few undergraduate museum studies programs in the nation, alumni can be found at organizations like the Smithsonian Institution, National Park Service, the National Archives, and National Geographic.

Keeping both imaging science and museum studies students involved is a priority for the CHI lab. Students have worked with MISHA since the original system prototype, which was developed in 2020 by a team of first-year students in an Innovative Freshman Experience course.

Sam Casimir, a third-year museum studies and English double major from Lewisburg, Pa., said working with MISHA fed her technical curiosity and bolstered her confidence.

“When I meet people established in the field, there’s often a moment of shock when I realize that my skills can help advance their research,” said Casimir. “Contributing to the advent of a tool like MISHA as an undergraduate student is really valuable.”

International hub

Decker, Easton, and Messinger emphasize that the future of MISHA will be co-created. As more institutions use MISHA, researchers propose new questions to explore.

Dot Porter, Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies curator of digital humanities, is in the early stages of building a MISHA at University of Pennsylvania. She plans to use it in her Vitale II Media Lab, which is focused on experimental, collaborative research centered on book history and digital humanities.

Multispectral imaging has been on Porter’s radar for years, but securing an imaging system was never financially feasible.

“The combination of the price and simplicity of the system was the selling point,” said Porter. “MISHA made it affordable to be experimental with multispectral imaging.”

In addition to continuing outreach, Decker, Easton, and Messinger aim to increase MISHA’s capabilities. With support from Tom Rieger ’74 (photography), Professor of Practice in museum studies, they are exploring how 3D printing can enhance MISHA’s hardware. The team is also prototyping MISHA 3D, which can image three-dimensional objects.

A prototype for MISHA 3D was created through Kate Gleason College of Engineering’s Multidisciplinary Senior Design program. Lilli Kelley ’25 (computer engineering) helped develop the new system software and joined the CHI lab after graduation to continue her work. This experience inspired her to pursue a master’s degree in imaging science at RIT.

“I’m thrilled to have found a place where I can combine my technical skills and creative interests,” said Kelley, from Charles Town, W. Va. “The most gratifying part is being able to contribute my skills toward something that does good in the world.”

Ultimately, the lab’s goal is to make RIT and Rochester an international hub for cultural heritage research. A key element to this, Decker said, is ensuring institutions of all sizes can benefit from MISHA.

“The opportunity to gain access to information that has been lost or unknown to current audiences inspires curiosity. We want to afford that opportunity to people across the world,” said Decker. “I’m excited to see what we can all do together.”

MISHA’s discoveries

MISHA helps reveal details that are invisible to the naked eye. As scholars image collection objects, their discoveries spark new research questions. Below are three examples of objects imaged by MISHA.

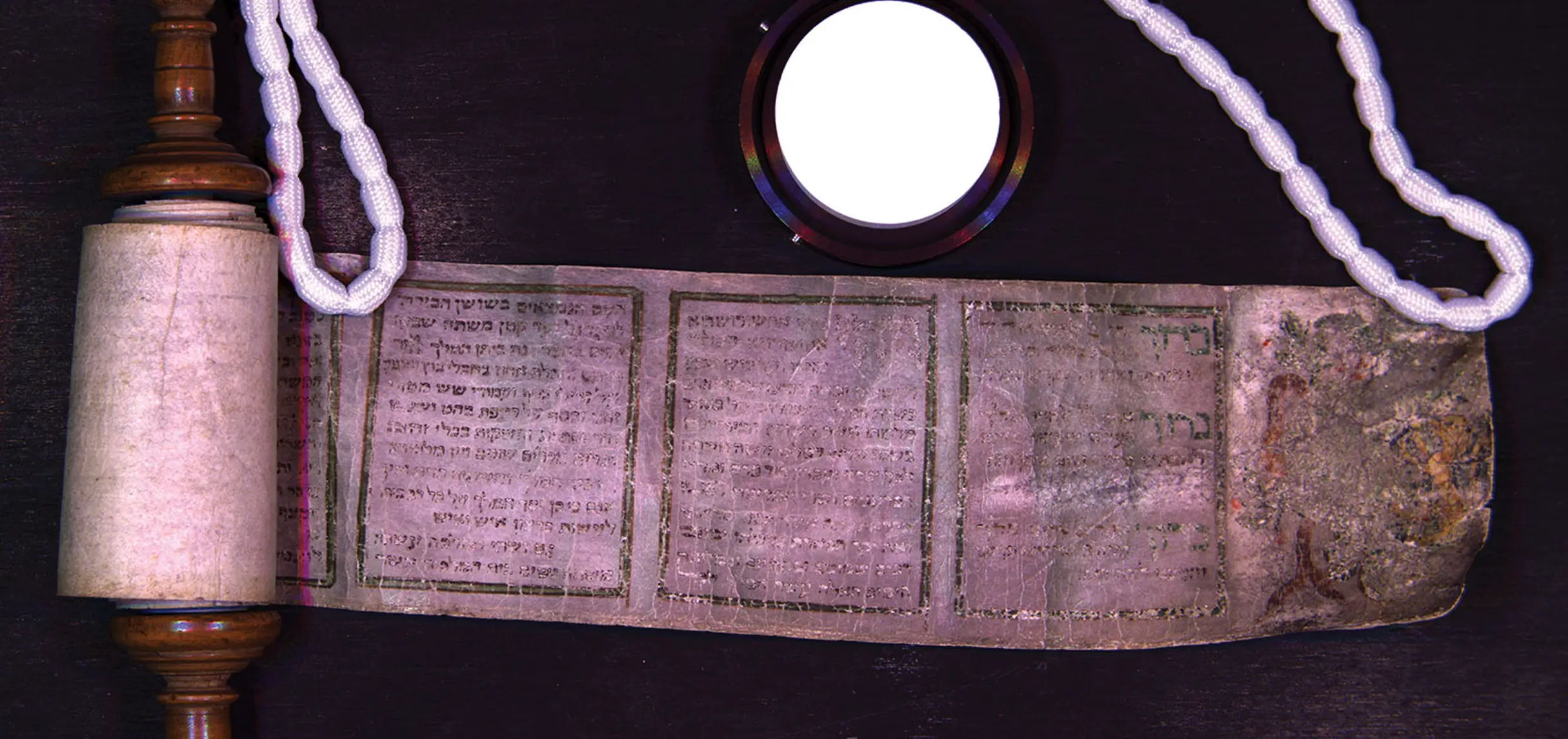

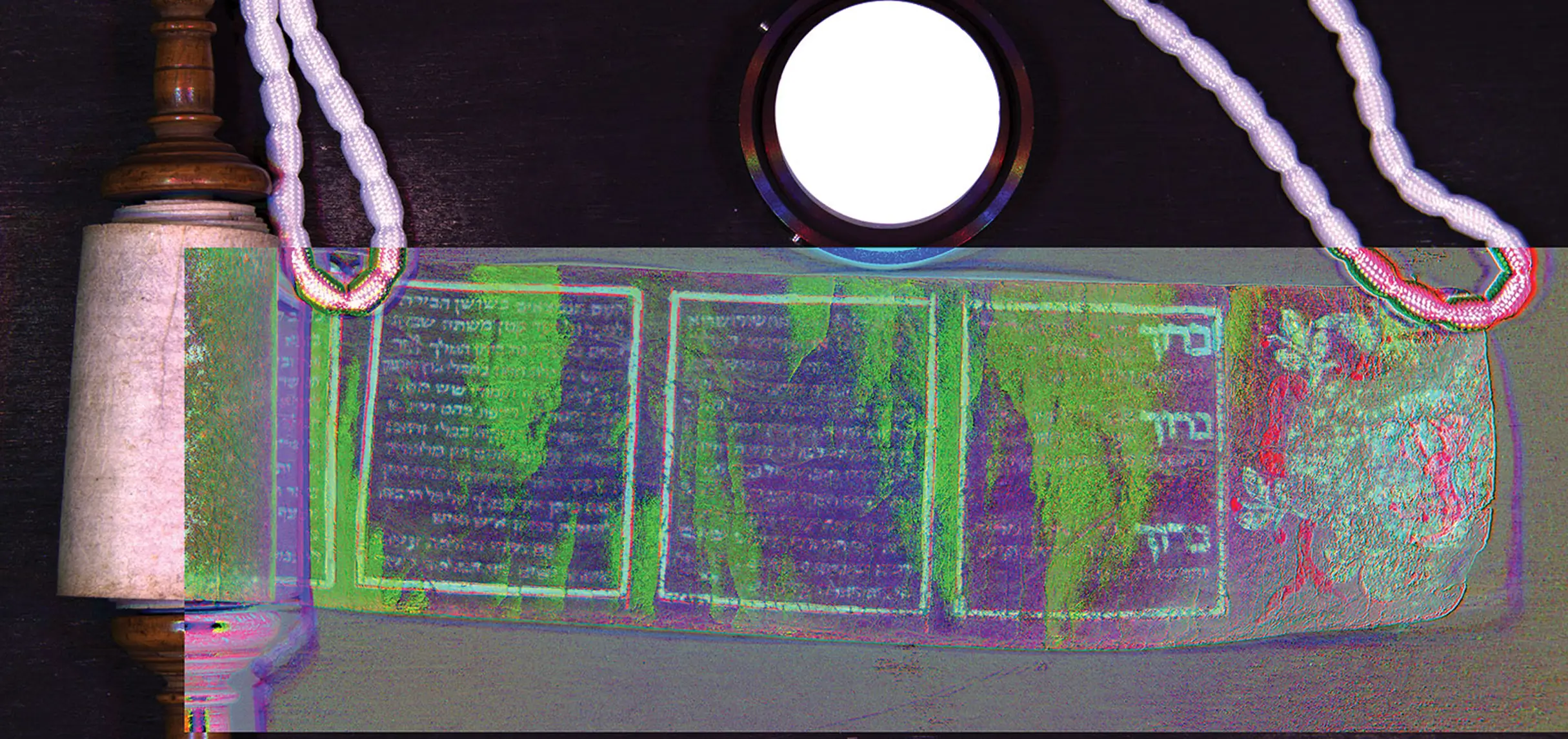

The Book of Esther scroll – Cary Graphic Arts Collection, RIT

The first illustration and text panels of this scroll were worn away over time. MISHA revealed the lost text and identified features from a coat of arms that enabled Curator Shani Avni, in collaboration with Jewish scholars Sharon Liberman Mintz, Dagmara Budzioch, and Yoel Finkelman, to re-date the scroll’s creation from the 8th century to the mid-to-late 18th century.

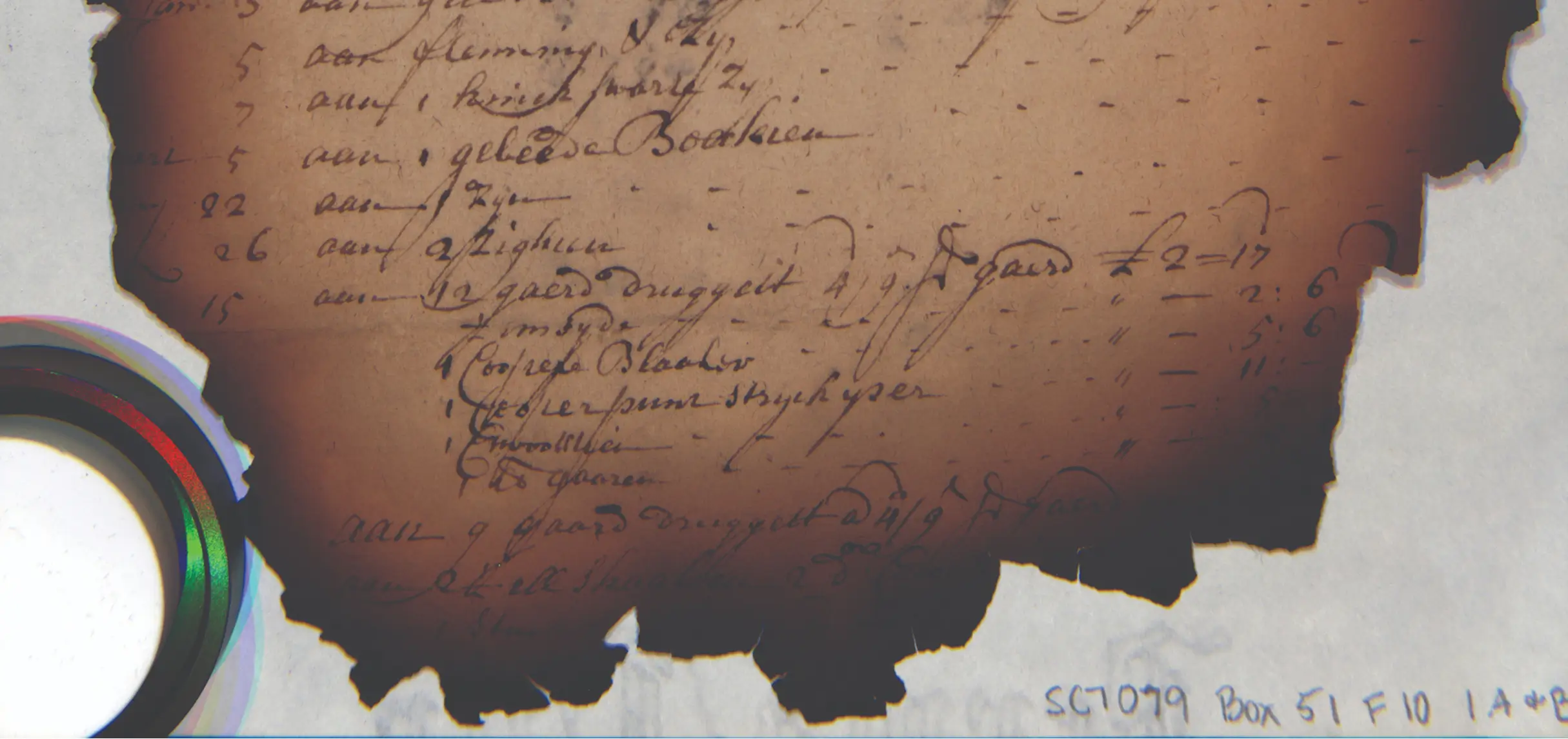

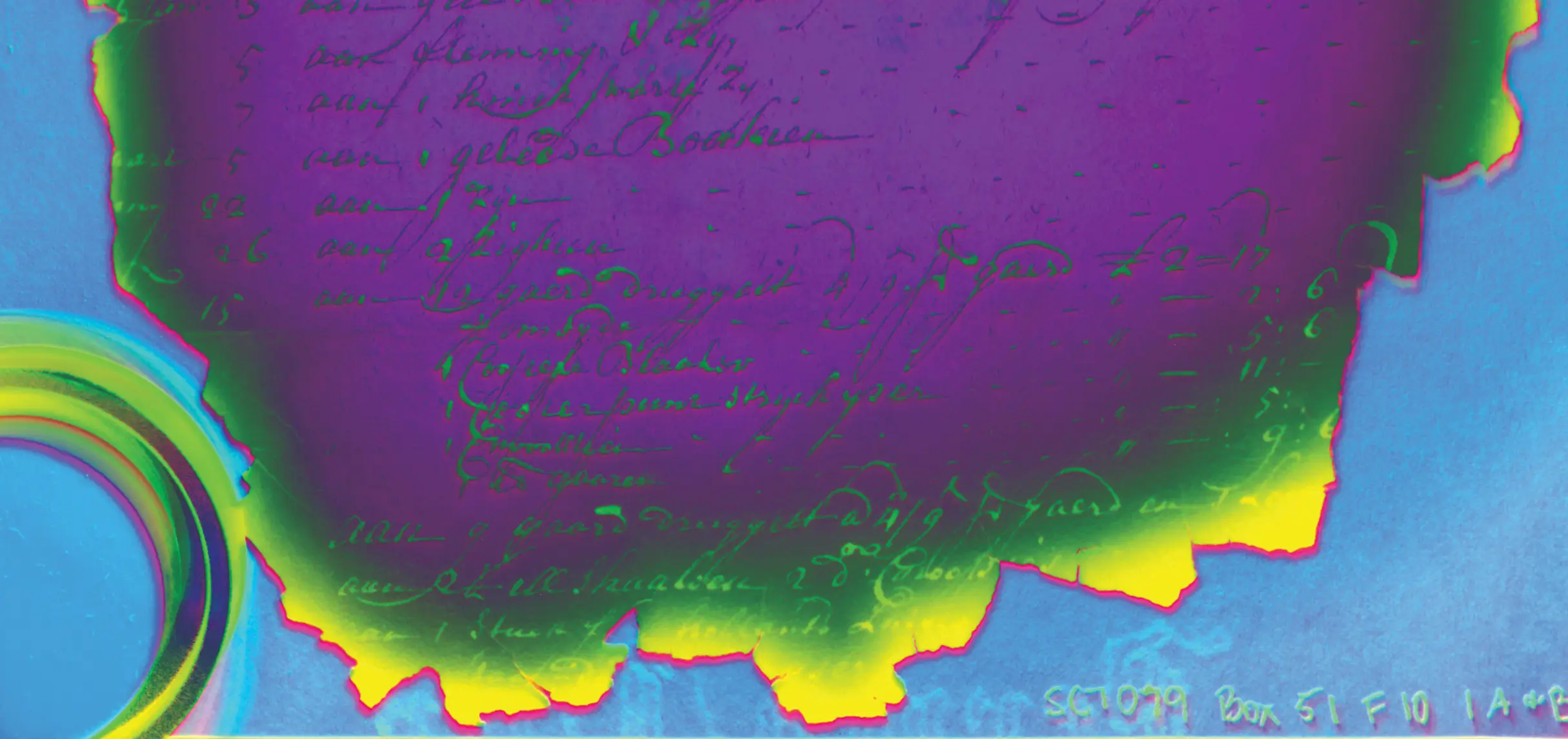

Charred documents—New York State Library, Van Rensselaer Manor Papers

In 1911, a fire raged through the New York State Capitol, destroying or badly damaging thousands of books, manuscripts, and other documents. MISHA illuminated some of the lost text on these charred fragments, which can be seen in green on the right.

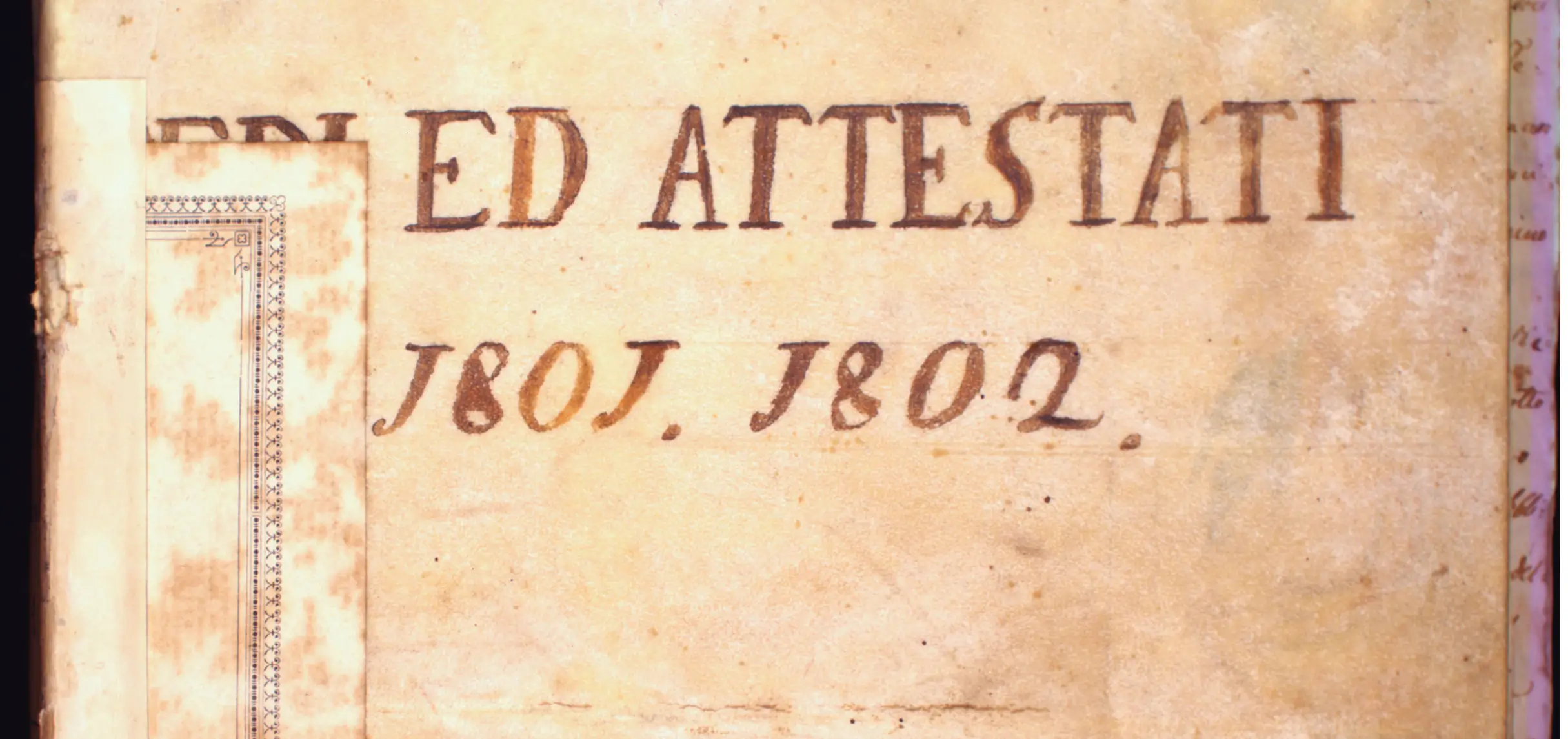

Certificates and Testimonials (Fides et attestata), Volume 7, 1792–1794—State Archive in Dubrovnik

This object was selected for imaging after archivist Paula Zglav noticed traces of lettering on the volume’s binding cover. MISHA revealed that, before being repurposed for binding, the document was a ship’s certificate issued to Captain Stjepan Valjalo. Further processing revealed the name of the ship and the identity of Valjalo, while subsequent archival research uncovered the list of crew members and the captain’s full story.