Can Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles Break the Blood-Brain Barrier?

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that can result from bacterial infections. If the bacteria enter the bloodstream, the host immune system may become hyperactivated and cause damage to the body—including damage to the blood vessels in the brain, which are responsible for creating the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier allows essential nutrients into the brain while blocking the entry of unwanted molecules that could disrupt brain chemistry. Unfortunately, sepsis survivors often experience persistent disruption of their blood-brain barrier after recovery and are consequently more likely to develop neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

How can we study these inflammatory processes at the blood-brain barrier to develop better therapeutic treatments?

Novel research in Rochester Institute of Technology’s Gaborski NanoBio Materials Laboratory and Michel Research Group is now exploring how bacterial factors might contribute to blood-brain barrier disruption. A key focus is on bacterial extracellular vesicles—small cargo containers exchanged by bacteria as a means of communication. These vesicles carry factors that can trigger inflammation in human hosts, raising concerns that they may continue circulating in the bloodstream and promoting inflammation even after the invading bacteria have been neutralized by antibiotics.

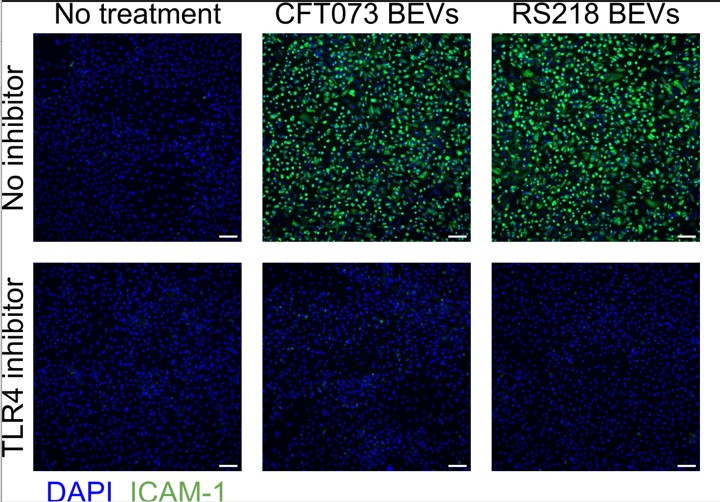

RIT student researchers have demonstrated that vesicles derived from E. coli bacteria can cause an inflammatory reaction when they contact the cells that line blood vessel walls. Furthermore, these students have identified the cell surface structures responsible for sensing the vesicles and initiating the inflammatory response. This information could one day prove useful in identifying therapeutic targets to help reduce inflammation in sepsis patients.

Building on the work accomplished so far, RIT students are now testing how these bacterial vesicles might disrupt an engineered blood-brain barrier model. It remains to be seen whether treatment with these vesicles can directly open gaps in the barrier. Another possibility is that the vesicles stimulate white blood cells to produce large quantities of inflammatory signals, which could contribute to blood-brain barrier injury. Whatever the outcome, the experimental results will no doubt increase our understanding of bacterial infections and the causes of sepsis, and will hopefully contribute to improving patient outcomes.