Researchers develop new method for predicting chaos

The tree-based algorithm approach outlined in paper published by ‘Nature Scientific Reports’

Giammarese/Rana/Bollt/Malik

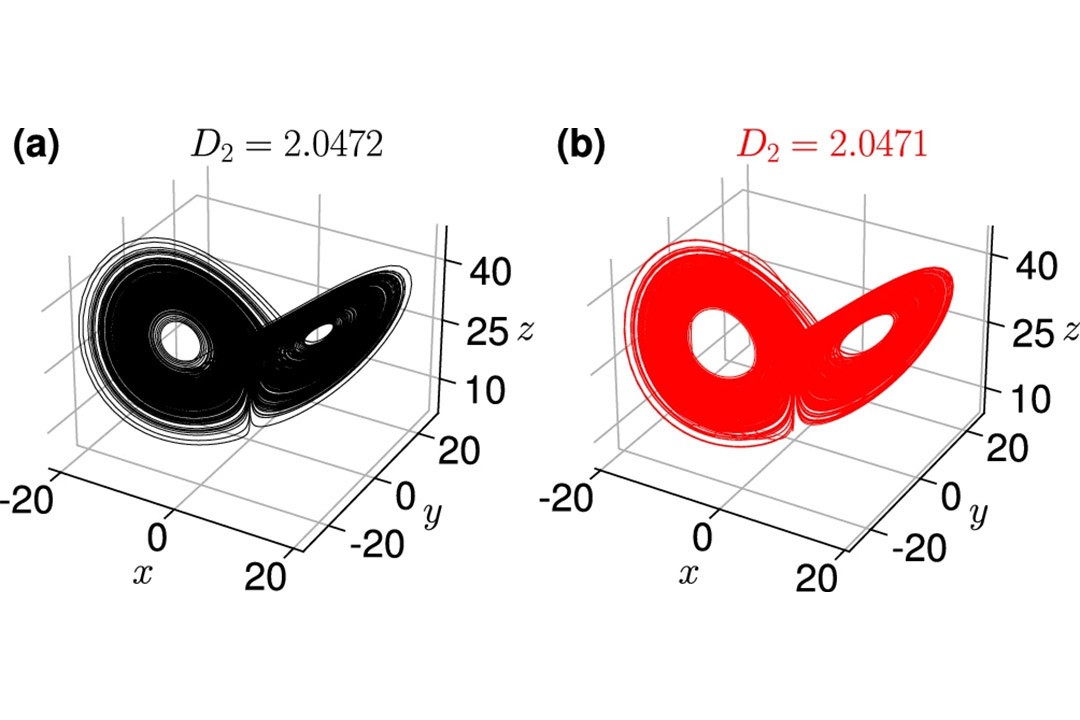

These figures show the research result of testing and predicting Lorenz system attractors, which shows deterministic chaos. The butterfly shape is characteristic of the butterfly effect of chaos.

A butterfly flaps its wings and weeks later a tornado touches down halfway around the world.

Mathematician Edward Lorenz used the butterfly effect to explain chaos theory in the 1960s. Now, decades later, a team from RIT has developed a method to predict chaos using less data, fewer parameters, and a more user-friendly format.

Adam Giammarese ’21 BS/MS (applied mathematics), ’25 Ph.D. (mathematical modeling) and Kamal Rana ’23 Ph.D. (imaging science), along with Nishant Malik, associate professor in the School of Mathematics and Statistics, published a paper on this new approach in Nature Scientific Reports.

Chaos theory explains how an incredibly small change in initial conditions can lead to a dramatically large and unpredictable change in output. The prediction of chaos is important in climate science and weather prediction and has applications in health and finance.

“Forecasting chaos is an impossible problem,” said Giammarese. “But if you can develop something that’s easy to use and can still forecast to a certain level to try to match other results out there, then that would be incredibly valuable. That’s what our paper was focused on.”

In 2019 when Giammarese and Rana were in Malik’s class on dynamical systems, a neural network-based algorithm for predicting chaos was being widely discussed in the field. Rana worked with decision trees, simple machine learning algorithms, in his Ph.D. research, which spawned the idea to apply tree-based learning to chaos prediction. As Rana moved on to another problem, Giammarese stepped in to take over the project.

While neural networks are more sophisticated, decision trees are classic machine learning baseline algorithms with fewer parameters.

“Anyone, whether they have expertise in chaos theory or whether they have expertise in machine learning, can use this really simple, straightforward algorithm,” explained Malik. “Neural-network-based methods are powerful and offer many advantages, but they’re often hard to interpret. Classical methods like decision trees are easier to understand, more transparent, and simpler to use.”

More complex computations need a lot of data and need to run many times, putting more strain on machine learning data centers. Decision trees require less data since they are simpler. Since data sets of weather and climate are relatively small, classical algorithms work well for these applications.

“The whole ethos of this research project is to make this as user friendly as possible,” said Giammarese. “I think we were trying to hit the research gap of bridging a classical method and a really difficult problem where we can use simple algorithms to solve really complex problems.”

In addition to Giammarese, Rana, and Malik, the late Erik Bollt, W. Jon Harrington Professor of Mathematics at Clarkson University, was a co-author.