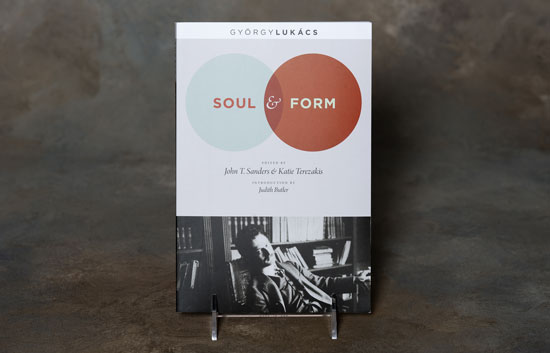

Centennial Edition of Philosopher György Lukács’s Book ‘Soul and Form’ is Released

Latest edition includes new essays and analysis

A. Sue Weisler

Noted philosopher György Lukács’ first book Soul and Form has been released in a new centennial edition. The work is co-edited by RIT professors John Saunders and Katie Terezakis.

György Lukács was a Hungarian philosopher, writer and literary critic who helped shape European political thought, Marxist theory and cultural criticism. He also founded what became known as the Budapest School of modern European philosophy.

Soul and Form was Lukács’s first book. Published in 1910, it immediately established his reputation, treating questions of linguistic expressivity and literary style in the works of Plato, Kierkegaard, Novalis, Sterne and others.

For this centennial edition, editors John Sanders, professor of philosophy, and Katie Terezakis, assistant professor of philosophy, both at Rochester Institute of Technology, add a dialogue entitled “On Poverty of Spirit,” which Lukács wrote just after he finished the essays of Soul and Form.

They also add an introduction by Judith Butler, professor at the University of California at Berkley and one of the foremost philosophers writing today. Butler’s introduction compares the key claims of Soul and Form to the initiatives of Lukács’ later work and to subsequent movements in literary theory and criticism. An afterword by Terezakis completes the collection; in it, she traces the impact of the Lukácsian notion of “form” within Lukács’s writing and as it comes to concern later critical theory and philosophy. The book is published by Columbia University Press.

“Lukács’ life and work encompasses a variety of issues, both aesthetic and political, that are absolutely central to the history of twentieth century thought and twentieth century politics,” says Sanders. “As we gain a little distance from—and additional perspective on—that century and its influence on us, we can gain considerable enlightenment through a re-examination of that life and work.”

“These essays still speak to us powerfully,” adds Terezakis, “of the difficulty of meaningful communication and the forms through which it can be achieved; of the need to criticize expressions of authority without taking on the mantle of authoritarianism; of the sort of suffering that characterizes human alienation and of its honest assessment. In other words, these essays engage ideas that continue to trouble and encourage us, not merely as topics in aesthetic or political theory, but as matters of binding human concern.”