Ceramics MFA candidate from Nigeria finds his signature at RIT

Rebecca Villagracia '26

Emmanuel Okechukwu created a series of ceramic sculptures exploring gender and sexuality symbolism in his native Nigeria for his thesis exhibition.

Emmanuel Okechukwu ’25 MFA (ceramics) carefully squeezes underglaze out of his slip trailing tube as the paint translates a traditional African textile print onto ceramic platters, jars, pots and sculptures.

Motifs from his native Nigeria are applied to his pieces, representing a unique convergence of Okechukwu’s African-inspired patterns with contemporary American art influence he gathered at RIT. Drawing African textiles on paper that are almost indistinguishable from fabric versions is an ability he recalled from his undergraduate days at Niger Delta University.

“I was trying to bring out everything I love (in my work),” Okechukwu said. “I didn’t know you could transfer textile design to ceramics. It was an odd relationship. But when I did it on a plate, it was beautiful.”

Okechukwu’s process is the result of a determined journey toward marking his work with distinct characteristics while staying true to his roots as a Nigerian ceramic artist.

He originally pursued graduate school in the U.S. to master the art of glazing his pottery. His first year in RIT’s ceramics MFA program featured pops of color and glossy flair.

“I was dunking pieces in every form of glaze,” Okechukwu said.

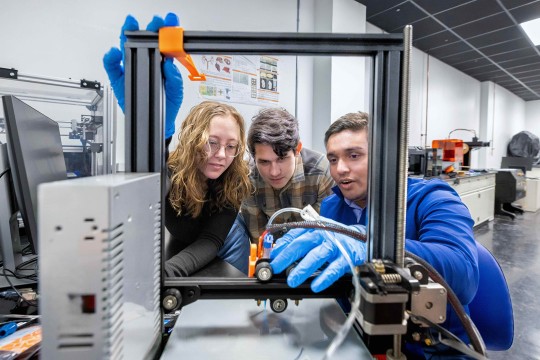

Elizabeth Lamark

Okechukwu strives to showcase his African roots in his work.

After a conversation with Ann Mowris Mulligan Endowed Professor Jane Shellenbarger and Associate Professor Peter Pincus, Okechukwu refined his vision.

“I discovered with American potters, it is not about the glazes,” Okechukwu said. “It’s about signature. In a room of 100 potters, how do you distinguish yourself to the point you do not need to sign your work?”

Today, line by line with his slip trailing tool, he makes his signature known with bold line work, intricate detail, and a symphony of underglaze colors.

He is an authentic storyteller, using ceramics to share his Nigerian lineage.

“I believe I am starting to have that voice. That’s something I learned here,” said Okechukwu, who enrolled at RIT on a full-tuition Crafts Scholarship. “Traveling is incredible. It opens you up to a world you didn’t even know existed.”

For his thesis exhibition in April, Okechukwu made a body of work exploring gender and sexuality symbolism. His ceramic sculptures are a response, Okechukwu said, to 20th-century British colonialism in Nigeria promoting rigid gender norms and discouraging non-binary identities.

The large-scale pieces have features aligned with non-binary and gender neutrality — from the hand-drawn textile designs and hairstyle references and colors, all the way to what they’re named. Collectively, they blur the definitions of masculinity and femininity.

“I do not identify as a female but I know I am not a macho male. I’m someone who is very in touch with my feminine side,” Okechukwu said. “The pieces are gender nonconforming. I want you to see my pieces as a human. But then you can’t decide if it’s a masculine or feminine form.”

Elizabeth Lamark

A selection of pieces from Okechukwu's thesis body of work.

Okechukwu’s breakthrough as an artist at RIT followed a tough-love moment. He made a platter he considered to be the best he ever made — a sentiment not shared during a faculty critique.

“That piece changed my life entirely,” Okechukwu said.

He worked with Shellenbarger and Pincus on his plate-making and, using the African textile designs, found his storytelling footing.

“Those plates helped me create a voice for myself,” he said. “For the first time in my life, I was satisfied with the work I made. That’s when I knew I had found my signature.”

Okechukwu is featured in numerous exhibitions through the spring, summer, and fall. After graduating, he plans to return to his K-12 art teaching roots, which he did for a handful of years in Nigeria.

Longer term, he has designs on opening a Nigerian high school focused on exposing students to the arts. Okechukwu said Nigerian school systems heavily emphasize STEM education, with little attention given to creative disciplines.

He envisions handing young creatives a better roadmap than he had to become a professional artist.

“I want to give students who are arts-inclined a voice from a young age,” he said. “My school is going to be strong in all branches of art.

“I’m currently living my best life,” he added. “I just want to make pots and I am happy. That’s a feeling I want people, especially younger people, to have.”