RIT researchers formulate a new “recipe” for stronger bio-printed tissue

Breakthrough work ensures bio-printed tissue keeps its shape and decreases damage to cells

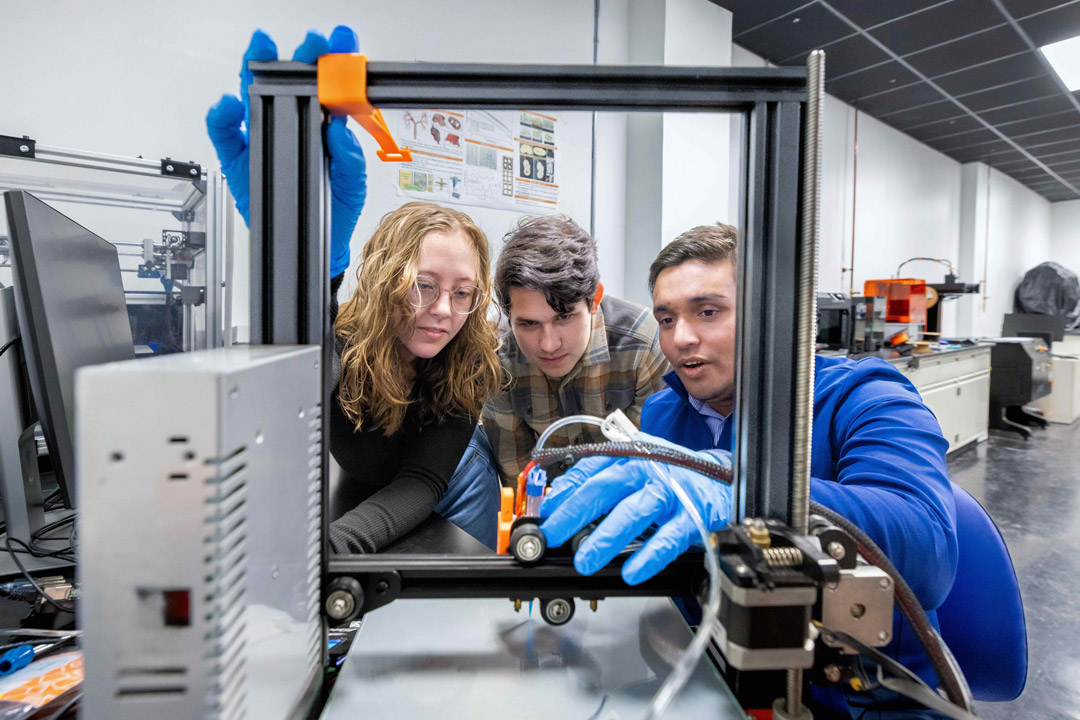

Carlos Ortiz/RIT

From left, undergraduate students Riley Rohauer and Perrin Woods work with Assistant Professor Ahasan Habib to develop hybrid hydrogels that can produce bio-scaffolds for tissue engineering using a novel hybrid hydrogel solution they developed.

RIT researchers have developed an ideal recipe that could advance how bio-tissues are produced.

Ahasan Habib, and Christopher Lewis, both professors in RIT’s College of Engineering Technology, and undergraduate students Riley Rohauer and Perrin Woods, found a solution to multiple challenges in tissue engineering today: finding a compatible gel medium to host human cells and a device that can print the delicate cells safely.

Their definitive range of properties and characteristics of the hydrogels may be useful for the development of bio-printed tissues that mimic brain, kidney, and heart tissue.

“We tried to design and prepare a dual cross-linkable material. We wanted to make sure we can control the various properties of the final 3D-printed parts,” said Habib, who is an expert in additive manufacturing, specifically toward functional bio-tissue scaffolds. “We needed to find a ‘sweet spot’ where we can extrude the matter to get a defined 3D structure, because we are preparing bio-ink—biomaterials plus cells together —and we wanted to be sure that we are not damaging the cells in the process.”

The team found that sweet spot and succeeded in:

- Developing a formula that would allow 3D-printed biostructures, or scaffolds, to maintain their soft, flexible shape during the layer-by-layer print process.

- Ensuring the variable recipes, referred to as characterizations, of natural and synthetic polymers combined effectively and the biomaterials extruded, or pressed, through a 3D printer remained viable.

- Building a custom 3D printer to adequately extrude, or push out biomaterials, with dual crosslinking abilities.

“Cells in the hydrogel are moving through a microscale tube, a nozzle,” said Habib “Our big goal is a dual crosslinking system. If we change the recipe of the material, how will it be impacted rheologically, physically, chemically and mechanically to eventually do a type of dual printing of bio-inks?”

Rheology refers to the physics of materials reactions when forces are applied, such as extruding the biomaterials through a 3D printer. Bio-printed materials, composed of cell tissue in a natural or synthetic polymer are required to build the essential scaffolds that mimic human tissues.

Solutions came from a project team made up of students and faculty from biomedical, mechanical and manufacturing engineering across RIT’s two engineering colleges. All contributed to experimental design, lab techniques and some elements of the research paper.

“It was a great learning curve for me,” said Rohauer, a third-year biomedical engineering student from Guilderland, N.Y. “As I was learning to create and characterize material. I was also learning scientific techniques up front.

“And as I became more confident, the data got better. Then Perrin came in and the print test corroborated what we were seeing with the chemical structure. It behaved the same way in ‘real life’ as it did on the machine. It was a really cool experience for me to see it move from one application to another.”

Woods, a fifth-year mechatronics engineering technology student, agreed. “We found the initiator, the chemical in the material that is going to photo-cross link. Dr. Habib has a really great vision for where this technology is going, both on the material and hardware sides. Tissue engineering is still preliminary, and these are the building blocks of a field.”

Woods, who is from Ithaca, N.Y., and will graduate in May, built a custom bio-printer that can shine ultraviolet light while printing in situ. Light triggers a chemical process that can turn bio-inks like the one the team developed into solid, stable gels.

One of the aims for this new test device was to ensure the biomaterial was cured and crosslinked, essentially while it is being printed. Often these processes are done separately, and this new technique and new 3D print device made the cross-linking possible and provides an advancement for continued development of bioinks as well as testing of other types of 3D printed tissues.

“You can 3D-print objects and tissues with a typical 3D printer, but the material may be wrong. Or you can get the right material, and you may not get the right geometries. That is where our lab and our materials come in,” said Woods. “We are able to say, bio-printing in a hydrogel can get you close to the tissue engineering solutions you need.”

The work was detailed in the January issue of the Journal of Functional Biomaterials. The research team consisted of students and faculty from RIT: Riley Rohauer, Kory Schimmelpfennig ’25 Ph.D. (biomedical and chemical engineering) and Perrin Woods; Ahasan Habib and Christopher Lewis: as well as Rokeya Sarah (Keene State College) who worked with the team as a research assistant June – August 2025.