Studying fiber alignment gradients

Despite their biological relevance, fiber alignment gradients had not been extensively studied in the lab. Our research addresses this gap by developing a new technique using microfluidic devices containing small, precisely engineered channels designed to manipulate fluid flow.

Cells in the human body migrate or move in specific directions, which are guided by various cues in their surroundings. One critical component in guiding this movement is collagen. Collagen is a protein abundant in our tissues. Specifically, collagen fibers can align in particular patterns, which create pathways that cells follow. This guidance system is known as "contact guidance" Contact guidance plays a significant role in both healthy processes, such as wound healing, and diseases, like cancer metastasis.

Scientists have traditionally studied cell migration on uniformly aligned collagen fibers in laboratory settings. However, in actual biological tissues, especially around tumors, collagen fibers often shift gradually from aligned to more disorganized patterns over very short distances. These subtle spatial variations in alignment are referred to as alignment gradients. These fiber alignment gradients add complexity to the tissue structure.

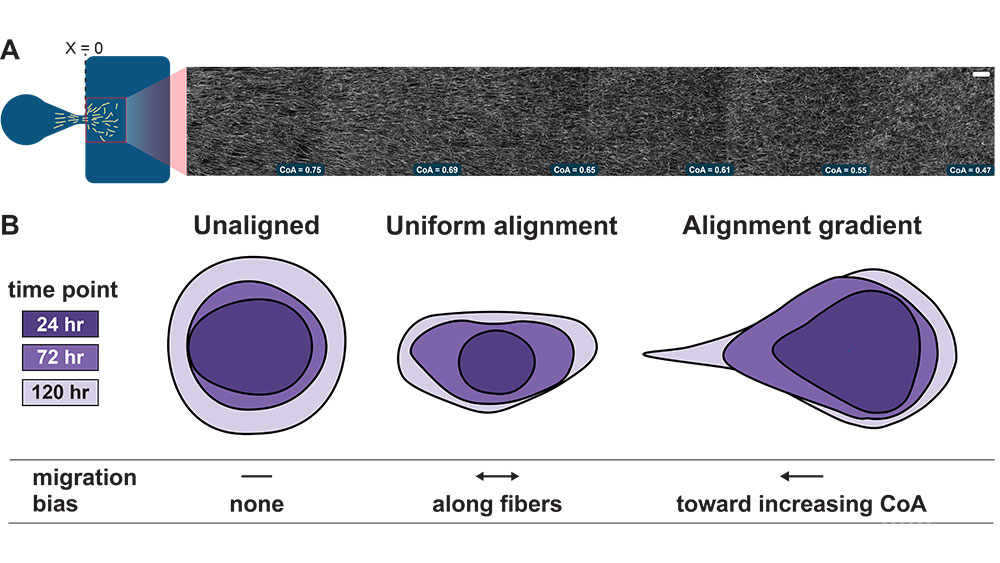

Despite their biological relevance, such gradients had not been extensively studied in the lab, as it was very difficult to recreate them accurately. Our research addressed this gap by developing a new technique using microfluidic devices containing small, precisely engineered channels designed to manipulate fluid flow. This allowed us to recreate these natural gradients in collagen fibers.

Next, by changing the input flow rate of collagen solutions within our designed microchannels, we successfully engineered precise collagen alignment gradients. These gradients can be engineered in several different length scales, ranging from less than a millimeter to several millimeters.

We then tested how cells responded to these engineered gradients. Our experiments revealed fascinating behaviors: human endothelial cells, important for blood vessel formation, moved more quickly and directly along the gradient compared to uniformly aligned or randomly organized collagen fibers. Similarly, breast cancer cells showed a clear preference, moving toward areas of higher collagen alignment. This suggests that cells interpret these subtle gradients as directional cues, significantly influencing their migration patterns.

This straightforward yet powerful approach provides researchers with a tool to investigate how cells interact with complex tissue environments. The broader goal of this work is to enhance laboratory models to more accurately represent actual biological conditions, thereby aiding in the development of therapies targeting diseases driven by cell migration.