Contact tracing key piece of combating COVID-19 at RIT

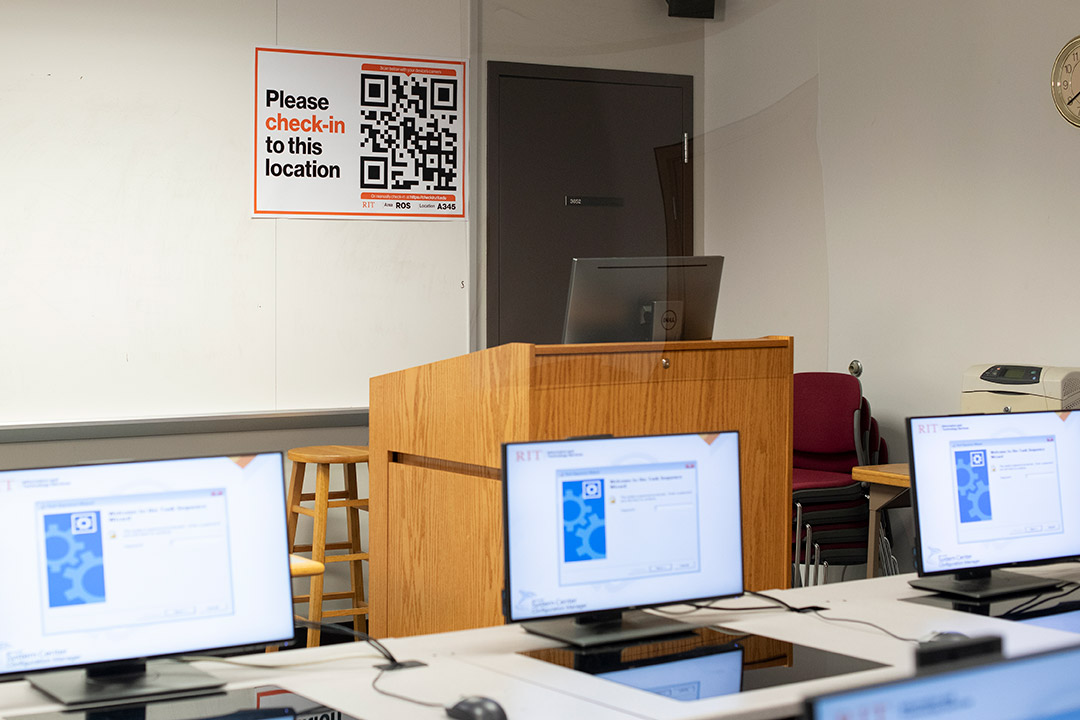

A. Sue Weisler

Contact tracing is one of the best public health weapons for preventing the spread of infection at RIT and in the wider community. RIT developed the Location Check-In Application for use on campus to aid in those contact tracing efforts.

During a time when health and safety are at the top of the curriculum, public health words such as contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation are part of the conversation at RIT.

While wearing masks, washing hands, and keeping a six-foot physical distance from each other create a personal line of defense against COVID-19, contact tracing is an overarching public health strategy to quash outbreaks.

Contact tracing is one of the best public health weapons for preventing the spread of infection at RIT and in the wider community. It is a proven method employed and perfected during previous health crises, including HIV-AIDS, SARS, and MERS. The meticulous process connects the dots between a person suspected of having COVID-19 and potentially infected individuals in their radius.

RIT medical staff communicates daily with the Monroe County Department of Health, via email or phone, and attends the biweekly conference calls for health leaders from the local colleges. “We share appropriate information so we make sure anyone in the RIT community is identified and cared for,” said Dr. Lindsay Phillips, RIT Student Health Center medical director.

The Monroe County Department of Health tracks every positive COVID-19 case and conducts a case investigation for every case to identify those who may have been exposed. The county alerts the RIT Student Health Center if a student has tested positive or may have been exposed to the coronavirus. Students may have gotten their tests through the Student Health Center if with symptoms, Tiger Test if selected for surveillance testing, or at an off-campus facility.

“It’s really important to know the evaluation for COVID is a combination of clinical presentation as well as that test,” Phillips said. “We know there are some false negatives with COVID tests, quite a high rate, and so we look at the whole constellation of symptoms. As soon as we make a decision to test someone, we consider that they could have COVID and we place them in isolation. And people they share sleeping space or other close quarters, we place them in quarantine.”

The risk for spreading infection or developing symptoms and exposing other people on campus can be mitigated if precautions are taken. The Student Health team educates students about what it means to isolate or quarantine and why they must not interact with other people—including friends in the same situation—and not circulate on campus during those 14 days.

Phillips praised RIT students for being proactive and conscientious about their health and the health of their friends. “When there is a positive case, we have students coming forward and saying, ‘I think I was also exposed in this way.’ Or, ‘I think you need to know that I was at this party and there were many people there and I don’t know who they were.’ And that reaching out is fantastic, and we’re really pleased to see it.”

Michael Edelman, contact tracer coordinator in RIT’s Student Health Center, leads a team of four part-time contact tracers using protocols created by the county health department and taught by Johns Hopkins University.

“A lot of the times when we contact the student, they are already aware of what is going on,” Edelman said. “There can occasionally be some frustration because we can’t share with them the name of the case that they’ve had contact with or the situation—like dining with someone. But we understand that this is very stressful for them and also a really big change if they need to quarantine for 14 days. We recognize that it puts a mental strain on the student, so we are screening them for anxiety and depression as we put them into quarantine and isolation and throughout the process.”

Residential life relocates students who live on campus if their living situation makes it difficult to isolate or quarantine. Students have access through the My Life Portal to the residential life, student health, and dining services. The contact tracing team works with students who live off campus to ensure they understand what quarantining means and conducts follow ups for the Monroe County Health Department.

The contact tracing team enrolls students (on and off campus) in a symptom-monitoring app. Students answer questions about their symptoms and learn about their medical risks for complications from COVID. The contact tracing team also monitors if students are experiencing mental health distress and would like outreach. Students in isolation complete a symptom survey twice daily, while those in quarantine check their symptoms daily.

“My experience with the students is that they want to do what is safest for the RIT community and prevent the spread of the virus,” Edelman said. “As far as the toll of being in quarantine, it’s hard for anyone to do. Especially if it’s a period of time where you would typically have an active social life and you’re going through stress with classes that are now being disrupted as well because they have to be done remotely.”

RIT Counseling and Psychological Services offers a weekly support group for students in quarantine or isolation to help them through this difficult time. Residential life team members also check on students every three days and more often for those who request it.

A Campus Life team checks in every three days with students living off campus. The contact tracing team also follows-up with these students in place of the Monroe County Health Department.

“The clinical evaluation and determination of whether or not someone has COVID takes two to five days,” Phillips said. “It depends on testing turnaround, how many days someone has been ill before they present to us. It depends on whether or not we are able to clearly identify some other process that is going on that is causing someone to be sick. That is why that period of time is variable.”

If a student’s COVID test comes back negative, medical staff at the Student Health Center reassesses them before they—and their contacts—can circulate on campus again. If the test comes back positive, or if Phillips’ team questions the accuracy of the results, the students will remain in isolation and quarantine. The Student Health Center and Monroe County Health Department would conduct a deeper investigation.

“It is expected that students will go in and out of isolation and quarantine all semester and it does not mean that a student made poor choices,” Phillips said. “You’re going to share a room with your roommate, if you have a boy/girlfriend you might spend time with them, if you have a job, you might find yourself accidentally in close proximity to someone. If you are sitting across from someone at the dining table and you have an interesting conversation and you forget to put your mask on while you are chewing your food…all these things are normal.”

Sometimes students do make unwise choices, and they deserve understanding, Phillips stressed. “It is true some people make mistakes and they are already living with the consequences of their mistakes, they don’t need anyone else berating them or making learning challenging for them because they are in isolation or quarantine because it already is hard enough.”