Mentorship and undergraduate research prepare RIT student for med school

Scott Hamilton/RIT

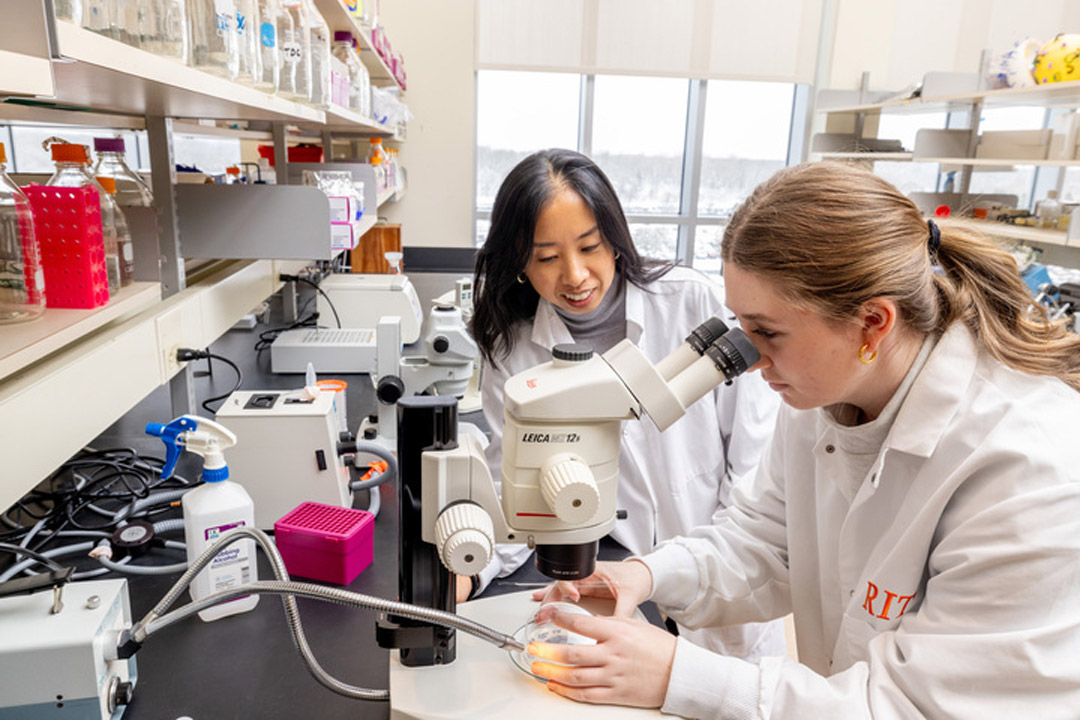

Undergraduate research is teaching RIT student Rachel Smith, front, lessons in perseverance, observation, and curiosity. Smith works at the microscope next to mentor Janet Lighthouse, assistant professor of biomedical sciences.

RIT student Rachel Smith is learning to think like a scientist, and her mentor is giving her room to grow.

As a second-year biomedical sciences major and honors student on a pre-med track, Smith sought out hands-on research experience to prepare for the rigors of medical school.

Smith sent a cold email to RIT Professor Janet Lighthouse and was invited to join her lab. Being proactive has allowed Smith to delve into the scientific process, learn technical skills, and find a mentor. Smith is seeing science happen, synthesizing what she is learning in class, and expanding her knowledge base, while building connections with faculty and peers.

“When I started, I learned basic molecular procedures and scientific topics,” said Smith, who is from LeRoy, N.Y. “I didn’t think I would be running these experiments and analyzing changes in gene expression. I’m able to tell what’s happening and if it’s successful or not. Pre-exposure to some of the topics and the basics of running simple procedures has helped with my classes.”

Lighthouse, RIT assistant professor of biomedical sciences, has a background in cardiovascular research and the effect of stress on the heart. Her previous work on cardiac fibroblasts, a cell type that helps the heart respond and adapt to different stressors, led to her current work on a class of diabetes medications called SGLT2 inhibitors.

Smith has learned to work with Caenorhabditis elegans (C.elegans), a tiny translucent worm, to model metabolic changes shared between humans and worms that result from diabetes or heart disease.

C.elegans is a 1-millimeter long worm, or nematode, which can be used to study the effects of stress throughout an entire organism. It enables Lighthouse to study why the SGLT2 class of drugs used in diabetes treatment can also benefit cardiac health.

“Even though worms and humans look and function very differently, there are still some basic physiological mechanisms that occur the same way in both species,” Lighthouse said.

Why do undergraduate research?

Research students gain an edge in critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and learning from setbacks, Lighthouse noted. Her own experience as an undergraduate research student presented a pathway to a career in science.

“I think getting involved in undergraduate research is really valuable to show students how diverse and dynamic science is, and that scientists are innovating, pushing boundaries, and challenging themselves on a daily basis to improve our understanding of how our world works,” Lighthouse said.

Hands-on experiences and mentorship are catalysts for student success, according to the Council on Undergraduate Research. Real opportunities and interacting with scientists allow students to gain competencies sought by graduate school admissions and employers.

Through Lighthouse’s mentorship, Smith is learning how to frame research questions, analyze data, and communicate findings at RIT’s annual Undergraduate Research Symposium.

“Just having research experience alone will help me in the medical school application process, but I think it’s important to be well rounded,” Smith said. "We also read and summarize papers and apply them to what we’re doing. It’s good experience to have.”