Unfolding the Universe

While speaking with a student over Zoom on a seemingly normal day in April 2021, Associate Professor Jeyhan Kartaltepe received a Slack message with news that would alter her career.

“Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god,” said Associate Professor Caitlin Casey, Kartaltepe’s collaborator from the University of Texas in Austin.

“What’s going on?” asked Kartaltepe. “We got it! We got it,” replied Casey.

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) had just revealed the proposals selected for the General Observer programs for the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) first year of operation. Panels of scientists had winnowed approximately 1,200 proposals into 266 programs approved for the telescope’s first year. The largest was COSMOS-Web, a massive study of thousands of the earliest galaxies in the universe to be led by Kartaltepe and Casey.

Since that day, Kartaltepe’s work with the most powerful observational instrument ever made has gone at light speed. The telescope had a long-awaited launch on Christmas Day 2021, released its first official images in summer 2022, and began collecting data for COSMOS-Web in January 2023. Ultimately, the telescope will help explain the origins of the universe.

“Everything about JWST so far has exceeded expectations,” said Kartaltepe. “The sensitivity is higher than people expected, and that almost never happens. This is better than we could have hoped for.”

Kartaltepe now has her hands full studying data from COSMOS-Web and other large JWST programs, while continuing to bolster her reputation as a teacher and mentor. Her work has gotten the attention of the astronomy community worldwide.

“She is a tremendous asset to RIT,” said Professor Bahram Mobasher, a longtime collaborator from the University of California Riverside. “RIT was already on the map, but she has really done a lot for that program.”

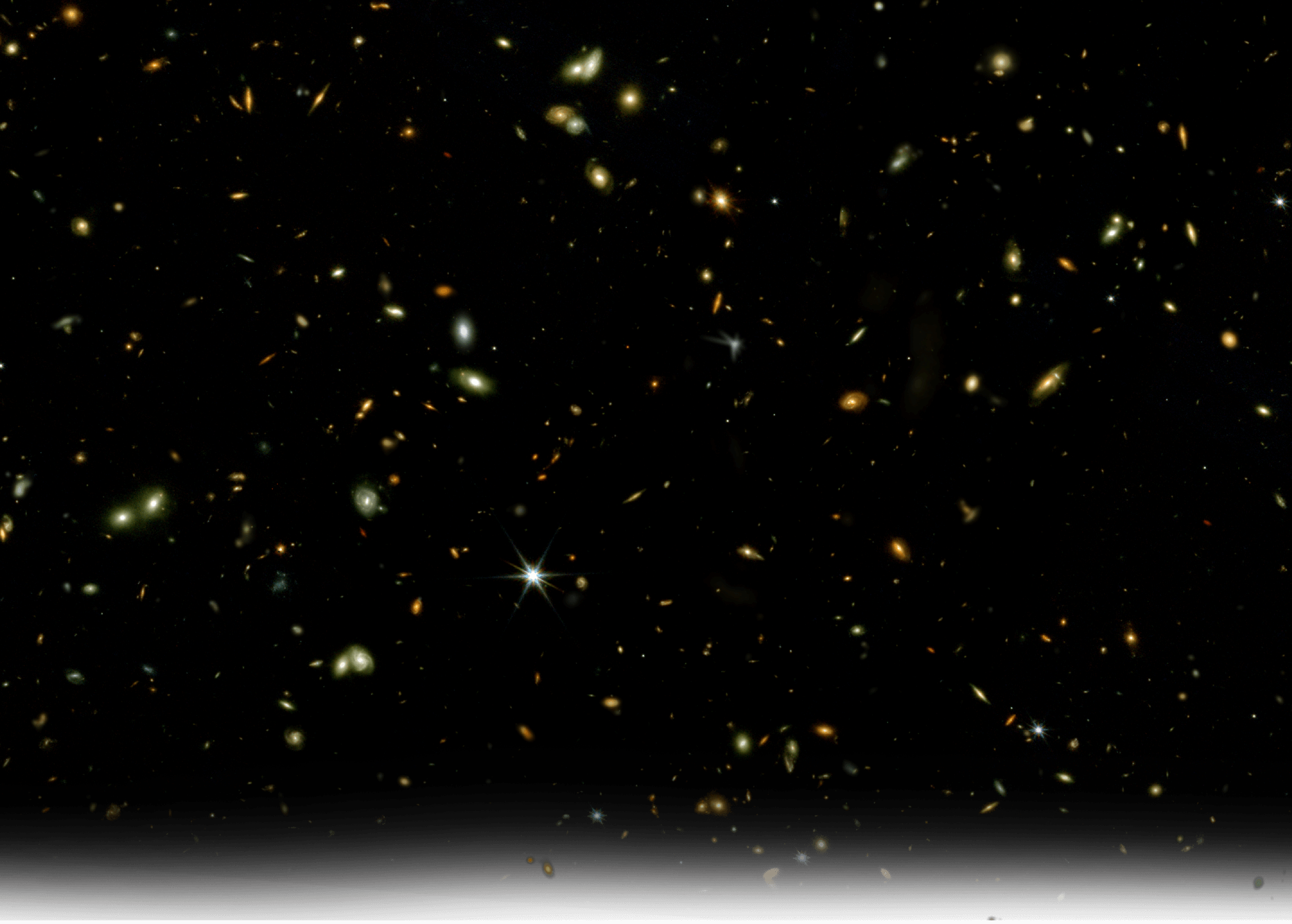

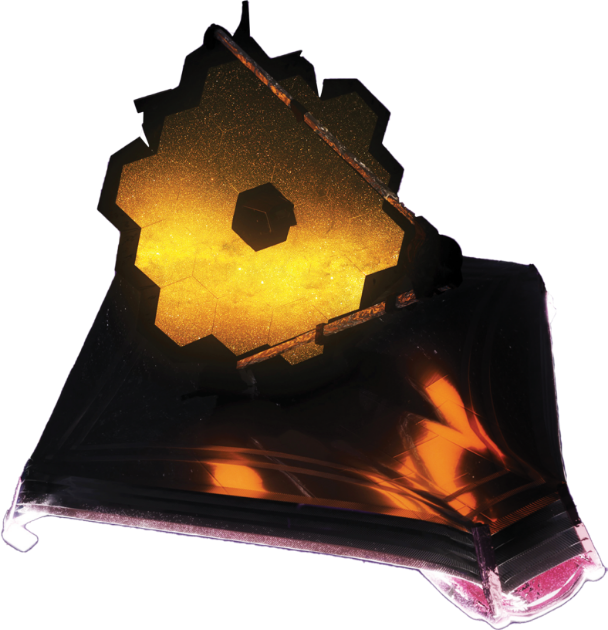

An illustration of the James Webb Space Telescope deployed in space, far left. The telescope has a large mirror made of hexagons that are being illuminated by the galaxy being observed. Otherwise, the top side of the telescope is in the dark. The underside is being lit by the sun. The telescope is set against a starry background.

What has the telescope shown so far?

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already begun to upend scientists’ previous assumptions about the universe.

The telescope was designed to observe the universe at near-infrared and mid-infrared wavelengths, which are longer than the wavelengths of visible light. That makes JWST a great tool for studying what the earliest galaxies in the universe looked like.

As light travels from a distant galaxy toward us, it is gradually stretched into longer wavelengths and shifted toward the infrared part of the spectrum. Since the universe is expanding, the most distant light from the earliest galaxies has been shifted to the longer, redder wavelengths that can only be detected through infrared. The higher the “redshift” of a galaxy, the earlier it formed.

Since JWST came online, scientists have been finding lots of examples of high redshift galaxies.

Associate Professor Jeyhan Kartaltepe is co-leading COSMOS-Web, the largest general observer program in JWST’s first year, and is a key player in other JWST programs including the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS), Public Release Imaging for Extragalactic Research (PRIMER), and the Next Generation Deep Extragalactic Exploratory Public (NGDEEP) Survey. While all of these programs look at galaxy formation in the early universe, they are different in scope.

At the two ends are COSMOS-Web and NGDEEP. COSMOS-Web looks at a relatively large portion of the sky but at relatively shallow glances, albeit still much deeper than anything possible before with the Hubble Space Telescope. NGDEEP, by contrast, looks at one point in the sky and stares at it for a long time.

By analyzing data from JWST taken for the CEERS study, Kartaltepe and her collaborators have found that the structures of galaxies in the early universe were much more diverse and mature than previously known.

The team examined 850 galaxies at redshifts of z three through nine, or as they were roughly 11 billion to 13 billion years ago, using images taken by both JWST and those previously taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

JWST’s ability to see faint, high redshift galaxies in sharper detail than Hubble allowed the team of researchers to resolve more features and see a wide mix of galaxies, including many with mature features such as disks and spheroidal components.

Out of the 850 galaxies used in the study that were previously identified by Hubble, 488 were reclassified with different structures after being shown in more detail with JWST.

Kartaltepe said COSMOS-Web will provide an even larger sample through 255 hours of observing time with the telescope.

COSMOS-Web began its observing campaign in January and will finish in January 2024, studying an area of the sky about three times the size of a full moon.

The program team released COSMOS-Web’s first images in March, but the bulk of data will become available in two batches this summer and winter.

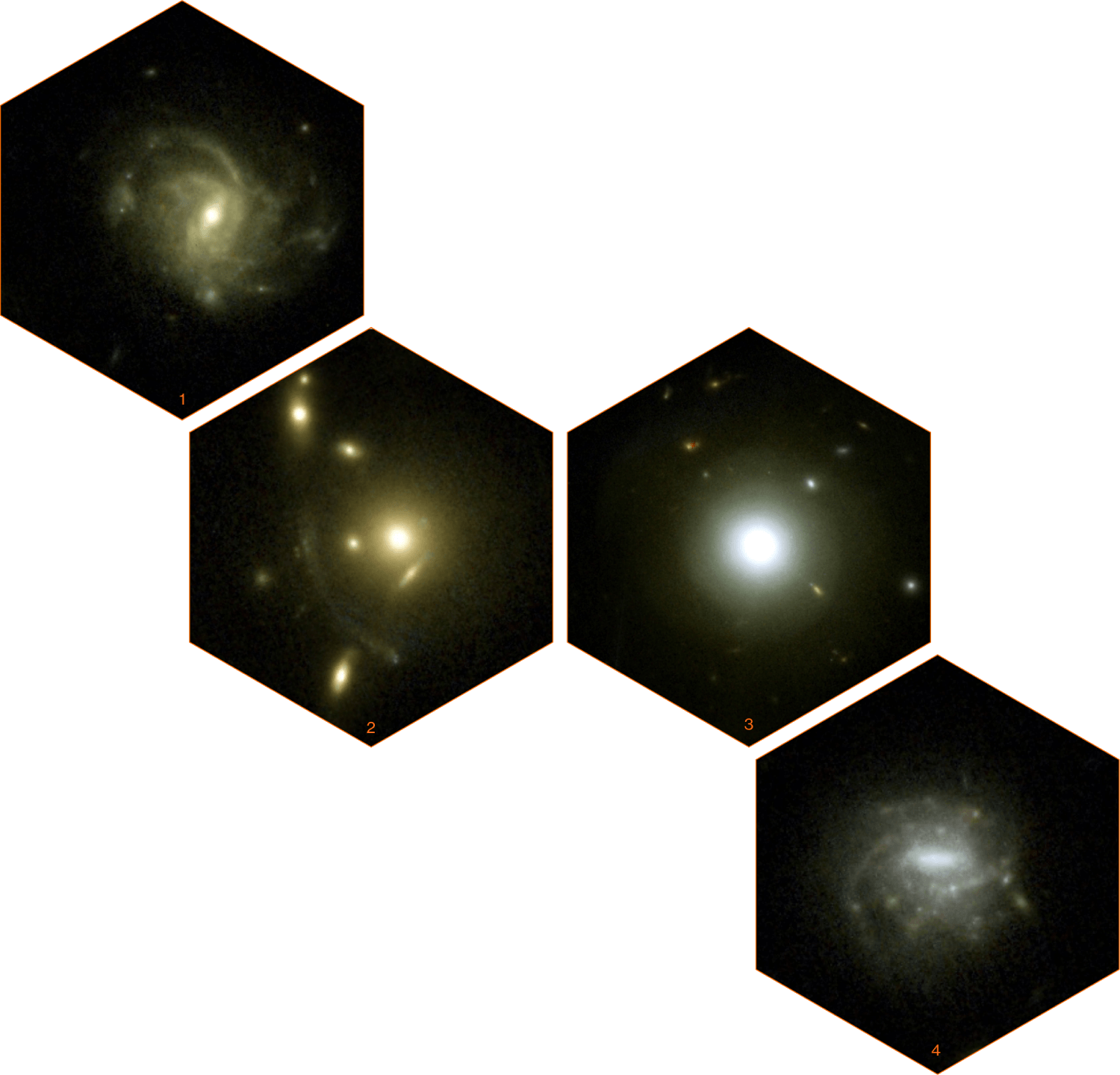

Images of four example galaxies selected from the first epoch of COSMOS-Web NIRCam observations, highlighting the range of structures that can be seen. 1 is a barred spiral galaxy; 2 is an example of a gravitational lens, where the mass of the central galaxy is causing the light from a distant galaxy to be stretched into arcs; 3 is a nearby galaxy displaying shells of material, suggesting it merged with another galaxy in its past; 4 is a barred spiral galaxy with several clumps of active star formation.

Image credit COSMOS-Web/Kartaltepe, Casey, Franco, Larson, et al./RIT/UT Austin/CANDIDE.